Victoria Chang was born in 1970 in Detroit, the daughter of an engineer and a math teacher, both immigrants from Taiwan. Their daughter inherited a quantitative aptitude and earned an MBA from Stanford University, eventually working in various business jobs such as management consulting and marketing.

But Chang’s interests were always varied and broad. Her first two degrees, from the University of Michigan and Harvard University, were in Asian studies. As her interest in poetry and writing grew, she pursued an MFA from Warren Wilson College, and she currently is the program chair and a faculty member at Antioch University’s low residency MFA program.

“I grew up in Michigan,” Chang told her friend and poet Ilya Kaminsky in an interview for Divedapper. “It was assimilate or die. I often failed at assimilation but learned all of the skills along the way through trial and error. Sometimes the people I wanted to assimilate with didn’t see me, but I still got the practice. I’m not saying it’s a positive thing. It just is. Therefore, I’m nobody, who are you? Yet, I’m also everybody. I think that shows up in my creative work as well.”

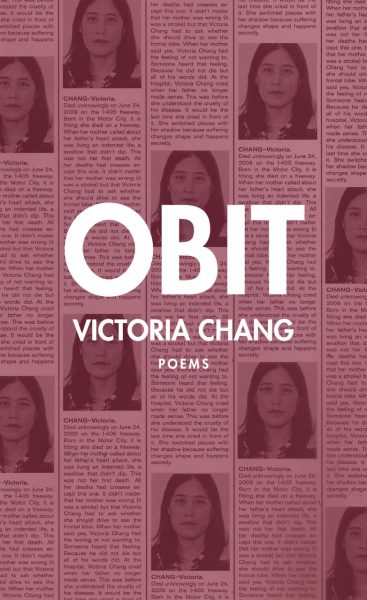

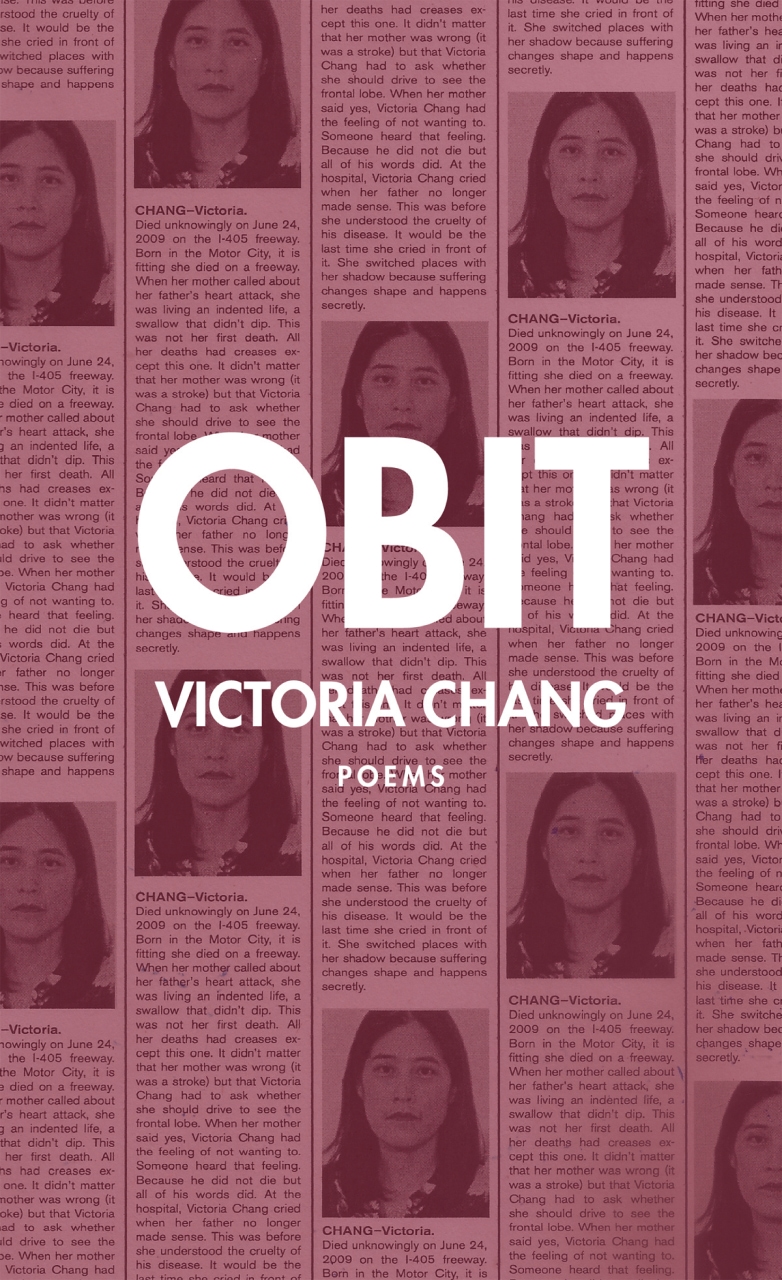

Her fifth collection of poetry, Obit, met with a chorus of critical praise. It was a finalist for a National Book Critics Award and listed as a best book of 2020 by Time magazine, the Boston Globe and NPR. “To say simply that Chang takes the Modernist’s music and makes it new again, makes it alive is to say only half-truth,” writes Kaminsky, “for she truly re-inhabits it, re-kindles the flame. This radically new music is political yes, but it is also ecstatic.”

Chang’s mother died on Aug. 3, 2015 of pulmonary fibrosis, and her father suffered a catastrophic stroke in 2009. These dates appear and reappear at the top of prose poems in Obit, which are compressed into narrow columns that mirror a newspaper obituary or a tombstone. The poems are for her parents, but also for all that dies when a loved one dies: “The Head,” “Appetite,” “The Clock,” “Optimism,” “Oxygen,” “The Blue Dress.” Sprinkled among the obits are tanka poems Chang addresses to her children.

Known for her unflinching gaze, formal brilliance and rueful wit, Chang said the poems that poured from her after her mother died were more personally revealing than those in her previous books.

“Because for me, it’s always about vulnerability,” she told Heidi Seaborn of The Adroit Journal. “I was taught to be strong, and to be that pillar, all the time. So, to actually show and reveal what I really feel, to be vulnerable, was just not in my vocabulary growing up. It took my mom’s passing to be just a smidge more comfortable with that.”

Chang distilled her grief during a feverish two weeks by writing “obits” for all she had lost in the world. The roughly 70 obit poems are repetitive, in the way grief is both repetitive and asynchronous, lonely and universal. In a poem called “The Head,” Chang writes, “My/ mother, now covered, was no longer/ my mother. A covered apple is no/ longer an apple. A sketch of a person/ isn’t the person. Somewhere, in the/ morning, my mother had become the/sketch. And I would spend the rest of/ my life trying to shade her back in.”

Anisfield-Wolf juror Rita Dove responded strongly to Obit: “At first one might think: What a gimmick, to force each poem into the narrow column of a newspaper obit! How can these compressed language gobbets be called poems, anyway? And yet after the requisite announcements (name of the deceased, time, cause of death), each obit plunges to the source of its bereavement, skewering as it darkens, until I’m left speechless, bereft, in Keats’ ‘vale of soul-making.’”

In her interview with Kaminsky, Chang said, “the greatest influence of these poems was the obituary itself. The tone of the obituary is flat, matter-of-fact, and I actually read a lot of obituaries at that time to think about how to write my poems which are obviously different, but tonally similar.”

She added, “for me, at least, the vessel is as important as the words that go in the vessel. I think of it like a boat (or a vase) . . . the form often ignites the content.”

Chang edited the anthology Asian American Poetry: The Next Generation in 2004, and followed it with her first collection, Circle, in 2005. She remembers it arriving in a thin, bent, cardboard envelope and being thrilled to see it. Chang wrote four more adult poetry books and two children’s books, Love, Love and Is Mommy? In 2017, she was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship.

In the interview with Kaminsky, Chang said, “In the writing world, humility is so important, I think…. Humility is part of equity, social justice, in that we all have a right to be part of the writing community. Issues of access are always on my mind.”

Chang lives in Los Angeles with her family and two wiener dogs, Mustard and Ketchup.