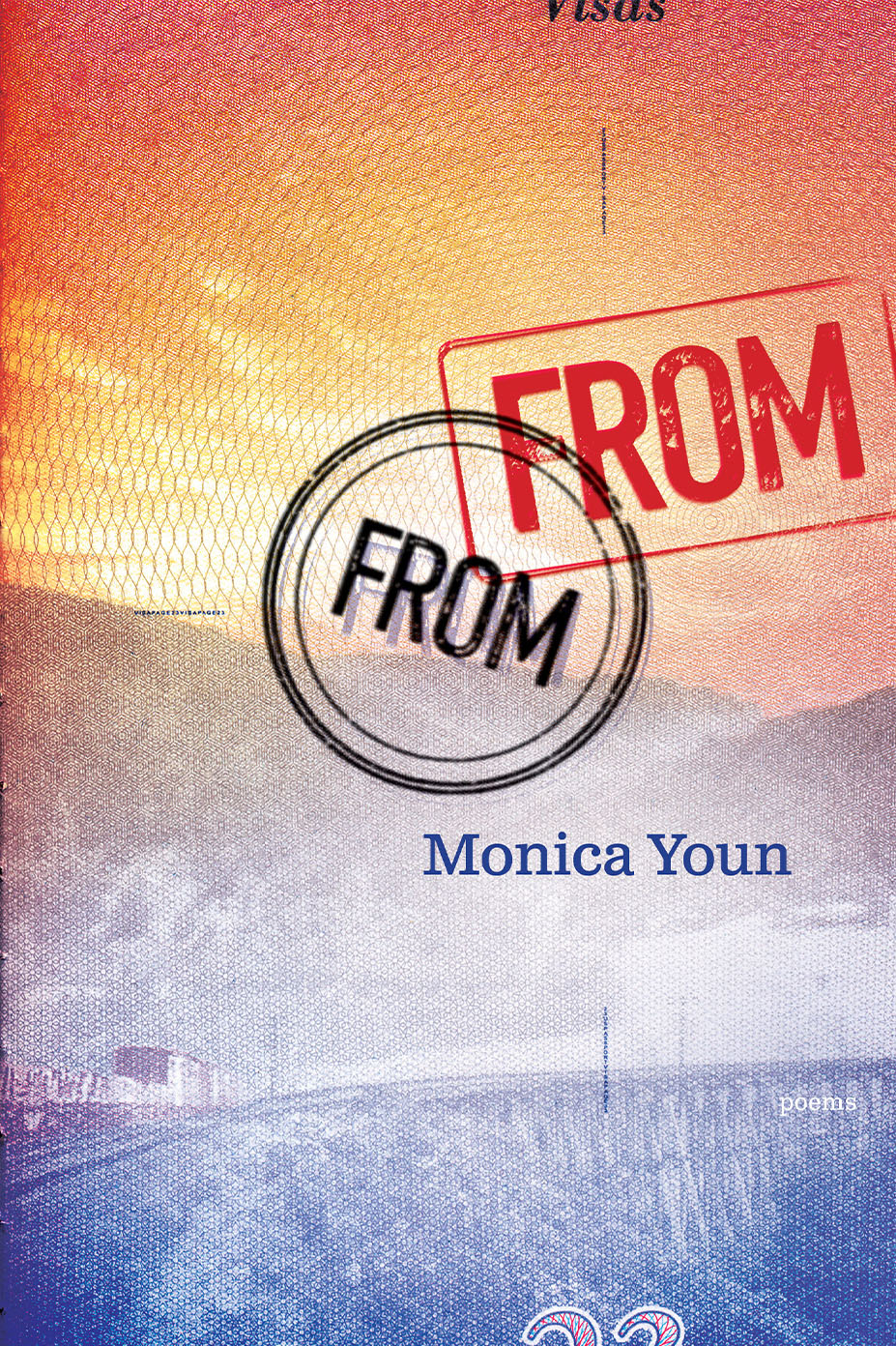

Some of the most storied, and studied, lines of 20th-century American literature landed in 1976. They came from a math and English high school teacher living in Hawai’i. She was 35.

“You must not tell anyone,” my mother said, “what I am about to tell you. In China your father had a sister who killed herself. She jumped into the family well. We say that your father had all brothers because it is as if she had never been born.”

This opening to “The Woman Warrior” is titled “No Name Woman.” It stands at the headwaters of much subsequent literature, a touchstone for Barack Obama as he wrote “Dreams from My Father” and Ocean Vuong who plucked from it the name “Little Dog” for his own stunning debut, “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.”

Four decades after its publication, The New Yorker asserted that “The Woman Warrior” had “changed American culture.” Its author, Maxine Hong Kingston, had no such aspirations. She had used marshmallows to distract her small son, then hunched over her typewriter, tapping out: “My aunt haunts me . . . I do not think she means me well. I am telling on her, and she was a spite suicide, drowning herself in the drinking water.”

Now 83, the writer, teacher, activist and pacifist makes her home with husband Earll Kingston in Oakland. She laughs easily, gardens often and steps lightly under a nimbus of long white hair. She is, the critic John Powers writes, “one of those rare figures who shifted American culture, and who keeps on being relevant. She tells stories about creating your own identity, not settling for the one the world tries to give you.”

Born in Stockton, California to immigrant parents, Kingston didn’t set eyes on China until middle age, part of a 1984 delegation sponsored by the Chinese Writers Association and UCLA. She and Toni Morrison took a boat down the Li River. To her astonishment, Kingston was able to find her father’s family well in the village of Sun Woi, near Canton, where her aunt, the No Name Woman, killed herself and her newborn. The baby, perhaps the result of rape, had been conceived outside marriage. In response to the affront of this pregnancy, a mob knifed the family’s livestock and ransacked their home.

“What I’m doing as a writer, as an artist, as a human being, is saying I am going to bring her to life, give her back her life, and I’m going to make all of us face her, and we’re going to find meaning for her life,” Kingston said in 1990. “We are going to rescue her. She has no name but I’m going to give her life and her immortality.”

When “The Woman Warrior” was translated into Cantonese, Kingston’s mother, Chew Ying Lan, a doctor in Sun Woi and a laundry owner in Stockton, could finally read it. The writer recalled her trepidation last year for an audience at the University of Southern California: “If you’ve read ‘The Woman Warrior,’ you know how angry it is, and that emotion goes through most of the book. When it was translated into Chinese characters, my mother could read it, and I was really nervous. But she said, ‘It’s so accurate? How could you know?’”

This response was validating for Kingston, but also confounding, because “The Woman Warrior” posits several scenarios for the No Name Woman, mixes in Fa Mu Lan – whom Disney calls Mulan — and blurs the boundaries between nonfiction and fiction. Some critics called it “fusion fiction,” others carped that its creator had distorted Chinese culture and coasted opportunistically on American feminism. As with the books of Philip Roth and Toni Morrison, some readers bristled at what they perceived as unflattering cultural portrayals. But Kingston wrote in a letter at the beginning of the debate, “This confusion really makes me feel good.”

She has found, she said last year, “somehow rebellion is a great energy for me. So, I could write differently from other people.”

Born in 1940, the oldest of six children, Maxine Hong was quiet. Her first language was Say Yup, a Cantonese dialect. She told The New Yorker that she spoke no English until she was five. Her father, Tom Hong, had twice tried in the 1920s to reach the United States, finally arriving, undocumented, from Cuba. In addition to the laundry, her parents ran a gambling establishment, and named Maxine after a lucky blonde who frequented it.

Maxine was drawn to writing like her father, a scholar in Sun Woi before he emigrated. She began crafting poetry at age nine. She saw her teen-aged essay on being American published in American Girl magazine. At 17, she entered the University of California at Berkeley with a raft of scholarships to study engineering, became distracted by English, by Earll, and by the growing anti-war movement. She switched majors, earned her English degree, married Earll the year she graduated, and had their son Joseph in 1963.

The couple eventually burned out on the souring scene in Berkeley, and on a layover in Hawai’i, found cause to stay. The family eventually moved to the small island of Lana’i, then mostly a pineapple plantation, where the isolation watered Kingston’s writing.

Four years later, “The Woman Warrior” garnered a rave from the influential New York Times critic John Leonard, won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award and a National Book Critics Circle prize. Kingston followed it with “China Men” in 1980. The new book mined the writer’s paternal lineage, again mixing alternative versions for its figures amid mythology, and documented legal barriers in the United States. The title is a repudiation of the slur “Chinaman” and is accurate to the way men from China referred to themselves.

Notoriously, Kingston’s editor at Knopf told her that she didn’t understand men, that hers weren’t lonely enough. The genre-defying “China Men” won the National Book Award in nonfiction.

In 2022, the Library of Congress published a handsome Kingston anthology. It contained her first two books: her novel from 1988 “The Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book” and a collection of essays. Its editor was Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of “The Sympathizer,” was a student of Kingston’s at Berkeley. He admitted to not being entirely ready to learn, and to having slept occasionally through her class.

“She showed the way, and it would take me a very long time to find my way,” Nguyen wrote. “That’s part of what it means to be a writer. Each of us has to find our own way, even if we were lucky enough to have someone show the way.”

For decades, Kingston has led a writer’s group for veterans, even as she was arrested in 2003 for protesting the impending Iraq war. Asked about her blend of writing and activism last year, Kingston said, “I don’t think of them as separate. To make your work public is already political.”

“Before I had language/ before I had stories, I wanted to write,” Kingston states near the end of her 2011 book, “I Love a Broad Margin to My Life,” a title she takes from Walt Whitman. “That desire is going away./ I’ve said what I have to say./ I’ll stop and look at things I called/ distractions. Become reader of the world,/ no more writer of it.”

Still, she confided to her USC audience last year, “It won’t let me go.”