More than a decade before the U.S military desegregated in 1948, American volunteers fought in racially integrated units – called the Abraham Lincoln Brigade — to battle fascism in Spain. Poet Langston Hughes covered these soldiers and the war against General Francisco Franco for the Baltimore Afro-American, a Black newspaper.

Hughes, an Anisfield-Wolf recipient, reached the Spanish Civil War by traveling through France, and he received a rousing ovation in Paris. “Yes, we Negroes in America do not have to be told what Fascism is in action,” he told cheering Parisians. “We know. Its theories of Nordic supremacy and economic suppression have long been realities to us.”

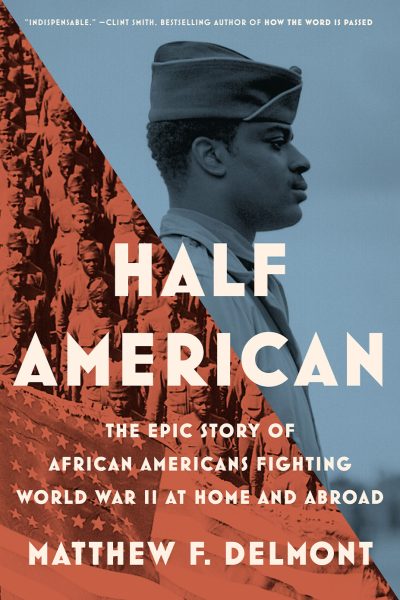

Historian and scholar Matthew F. Delmont begins “Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad” in Spain because, as he puts it, “the war really started for most Black Americans before Pearl Harbor. Fascism in Europe is something that Blacks understood as white supremacism.”

More than one-million Black American men and women served in World War II, and those experiences galvanized the demand to defeat white supremacy at home.

Perhaps the most celebrated cadre were the Tuskegee Airmen, but, for the most part, racial segregation meant that African American troops served largely in supply and logistical units or with the engineers or quartermasters. So, Sgt. Edward A. Carter Jr. — fluent in German, Hindi and Mandarin and a military veteran of the Spanish Civil War — was assigned work as a cook. He nevertheless worked his way onto the battlefield and posthumously earned the Medal of Honor for his valor.

Racist notions meant even the blood supplies were kept segregated.

“World War II wasn’t just a battle of strategy and will, it was a battle of supply,” Delmont told an audience at the Politics & Prose bookstore in Washington, D.C. “Without the contributions of Black Americans, the army couldn’t move, shoot or eat. Everything passed through the hands of at least one Black soldier. That’s really an important perspective on what it meant to fight and win this war.”

Medgar Evers, who grew up in Mississippi, was 19 when he arrived in Normandy, assigned to check cargo into the port. He made close friends with a French family. “It was the first time in his life that white people had treated him as a full human being, and he questioned if he could ever return to Mississippi,” Delmont writes. When he did, Evers rose to NAACP field secretary, organizing voting rights in the South. A white veteran assassinated Evers in 1963.

“For Black Americans, in World War II and in other time periods as well, patriotism and dissent went hand in hand,” Delmont told the bookstore audience. “That can’t be said often enough. For that whole generation of Black veterans, they fought during the war, they very much wanted to win the military aspect of the war, and then they came home and immediately started fighting for civil rights. They were fighting for a better version of America.”

The title for Delmont’s book comes from a 1941 letter from James Gratz Thompson, a 26-year-old cafeteria worker in Wichita, Kansas. He wrote to the Pittsburgh Courier, the nation’s largest Black newspaper, on the cusp of being drafted.

“Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?,” he asked. “Will things be better for the next generation in the peace to follow? Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for sacrificing my life? Is the kind of America I know worth defending?”

The poignancy of Thompson’s questions struck Delmont, who had taught college students World War II history for more than a decade. He is well versed in the common “Saving Private Ryan” sense of WW II Americans as the greatest generation. It’s a notion in popular culture that largely erases the Black experience.

Few of his students, or everyday Americans, know that the Courier mobilized thousands of readers, using Thompson’s letter as a springboard for a Double V campaign – victory abroad and at home. “Double V clubs formed in communities across the country and civil rights activists touted the slogan,” Delmont writes.

Anisfield-Wolf Juror Steven Pinker praised “Half American” as a “book heroically researched, rich in historical detail, well organized and written. This will probably stand as the landmark treatment for years to come.”

Delmont, Dartmouth College’s Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History, as well as its associate dean of international studies and interdisciplinary programs, found his curiosity piqued by the Black press.

Working on “Black Quotidian,” a digital book project with Stanford University Press, led Delmont to “Half American.”

The thousands of images and stories about everyday African Americans in the military – “That made me think,” he told the History News Network, “what would the war look like from the Black perspective, and was it possible to tell that story more broadly than it had been told before?”

The book does so, says Anisfield-Wolf Juror Pinker: It “rewrites our understanding of ‘the greatest generation’ in the ‘good war,’ given the shocking discrimination and harassment of millions of patriots willing to risk their lives in it. It’s also a neglected affirmation of the oft-forgotten but massive African American contribution to the country. It was pivotal in the Civil Rights revolution, since the absurdity of a segregated arm fighting Nazism led to the first complete desegregation of a government institution, whose success inspired Brown v. Board of Education and all that came after.”

Delmont is the son of Diane Delmont and Frank Bowman. His mother, a flight attendant and housekeeper, raised him in Minneapolis. Delmont, an only child, attended a military high school and earned his degrees from Harvard and Brown universities.

His doctoral thesis became his first book, “The Nicest Kids in Town,” an exploration of race and culture via American Bandstand in Philadelphia in the 1950s.

He lives in Etna, New Hampshire, with his wife Jacqueline Wernimont, the Distinguished Chair of Digital Humanities and Social Engagement at Dartmouth College. They have two children.