Readers flock to poet Saeed Jones for his mischief, his warmth, his gift with language and what the Kirkus Prize calls his “tenacious honesty.” More than 226,000 people follow his prodigious tweets. His newish podcast, “Vibe Check,” co-hosted with two other Black gay men, is exuberantly smart.

A Pushcart Prize winner, Jones is lauded for his attention to poetics and a clear-eyed telling of uncomfortable truths.

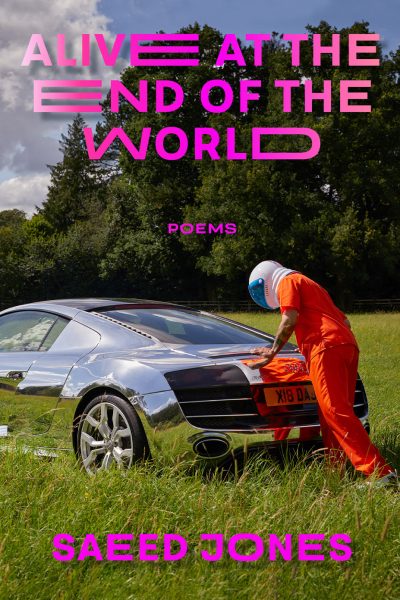

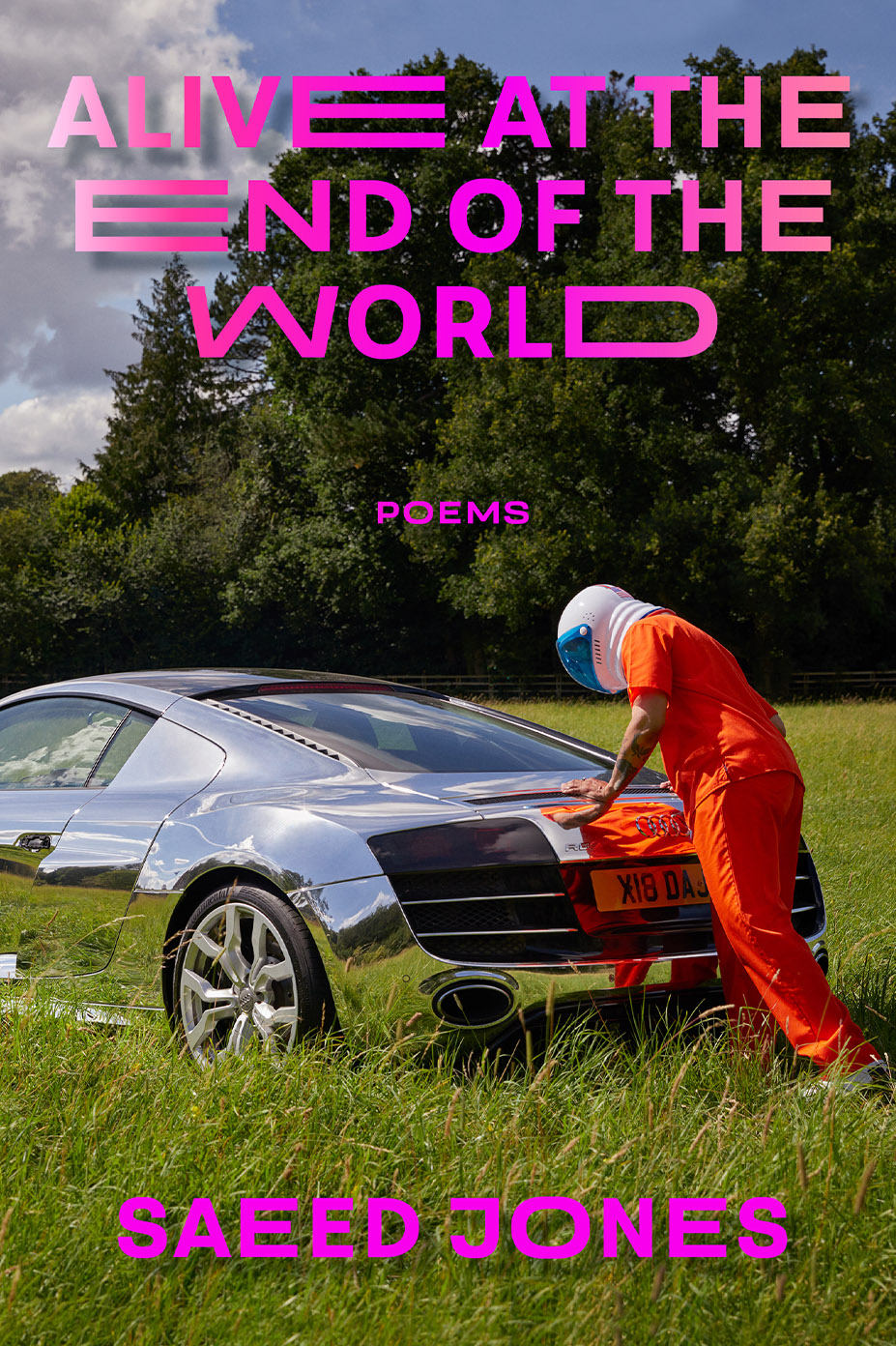

“Alive at the End of the World,” Jones’ second collection, contains 46 poems that sweep from strict verse to prose paragraphs. Anisfield-Wolf juror Rita Dove calls the book “an aching reminder that a queer Black man leads a meta existence; he cannot live without thinking about living, constantly negotiating the everyday with an eye to the peril that can intrude at any time, from police violence to the minutest reactions from highbrow bigots.”

Jones himself sees the collection deepening his relationship with humor and Black history. He identifies a 13-line poem, “That’s Not Snow, It’s Ash” as “the quiet, bewildered heart of the book.” He wrote it on a snowy weekend in Columbus, Ohio, in February 2020. “I wish someone had warned me that the end of the world could look like a peaceful Saturday morning,” Jones writes in the notes. The poem reads:

You are no singer, but one night

a song is stolen from you,

never to be returned. The loss

is like a dream about your lover

burned alive.

In the morning

he mumbles making breakfast,

favorite mug in hand, fine.

But you saw what you saw.

You drink your coffee, pat his thigh

and watch the snow fall outside,

pretending you don’t smell smoke.

He’s fine, you think. We are fine,

Note that Jones ends the poem with a comma, not a period. The critic Stephanie Burt says that Jones’ craft allows him to “investigate the almost unsayable.” And Dove notes that the poet “is a sublime signifier, streetwise and erudition-weary, adept at switching dialects and voices that toggle between joy and grief with such lightening felicity, the reader can’t be quite sure if she should be laughing, crying, or perhaps both at once.”

Saeed Jones was born in Memphis and raised in North Texas by his mother, Carol Jean Sweet-Jones, who died suddenly in 2013.

“My mother was my first champion,” Jones said. “She always encouraged me to read and write. And she seemed to be the only person who was entirely unsurprised when it started paying off in terms of pathways and opportunities. I think she always knew I would become a storyteller.”

Jones earned an undergraduate degree from Western Kentucky University and a master’s in fine arts from Rutgers University. His 2011 chapbook was “When the Only Light is Fire” morphed into his first full collection, “Prelude to Bruise.” “Prelude” won the 2015 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award for Poetry. It was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Jones became the executive culture editor at BuzzFeed. He co-hosted its morning show “Am to Dm” from 2017 until 2019. And he wrote BuzzFeed’s popular advice column “Dear Ferocity,” the source of his Twitter handle. His next book, the memoir “How We Fight for Our Lives,” was “a rhapsody,” according to critic Roxane Gay. It won the $50,000 Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction in 2019.

But after a decade in the city, Jones felt ready for a change. “Seemingly overnight, the vibrant energy of New York City became the relentless and expensive anxiety of New York City,” Jones wrote in an essay for Werk-in-Progress. On a 2018 visit to Columbus, Jones noted its striking gay culture, its cadre of writers, its reasonable rents, its cozy bookstores, its kind, Midwestern vibe. And something else:

“I walked into the McDonald’s and a group of old black men sat at a table, reading newspapers, drinking coffee and laughing,” he wrote. “Deep, black laughter. Hearty laughter. The way black people laugh in Toni Morrison novels. When they saw me, they let their chuckles settle and said ‘Good morning, young man’ almost in unison. I smiled and politely nodded. The young man at the register was just as warm, just as black, as was his coworker. I remembered then that Toni Morrison was from Ohio and thought ‘black people have been happy here for quite some time.

“Because, quiet as it’s kept, black people are everywhere and if you don’t understand that, you don’t understand America.” In Columbus, Jones found the space to write “Alive at the End of the World.” He is busy growing new projects.