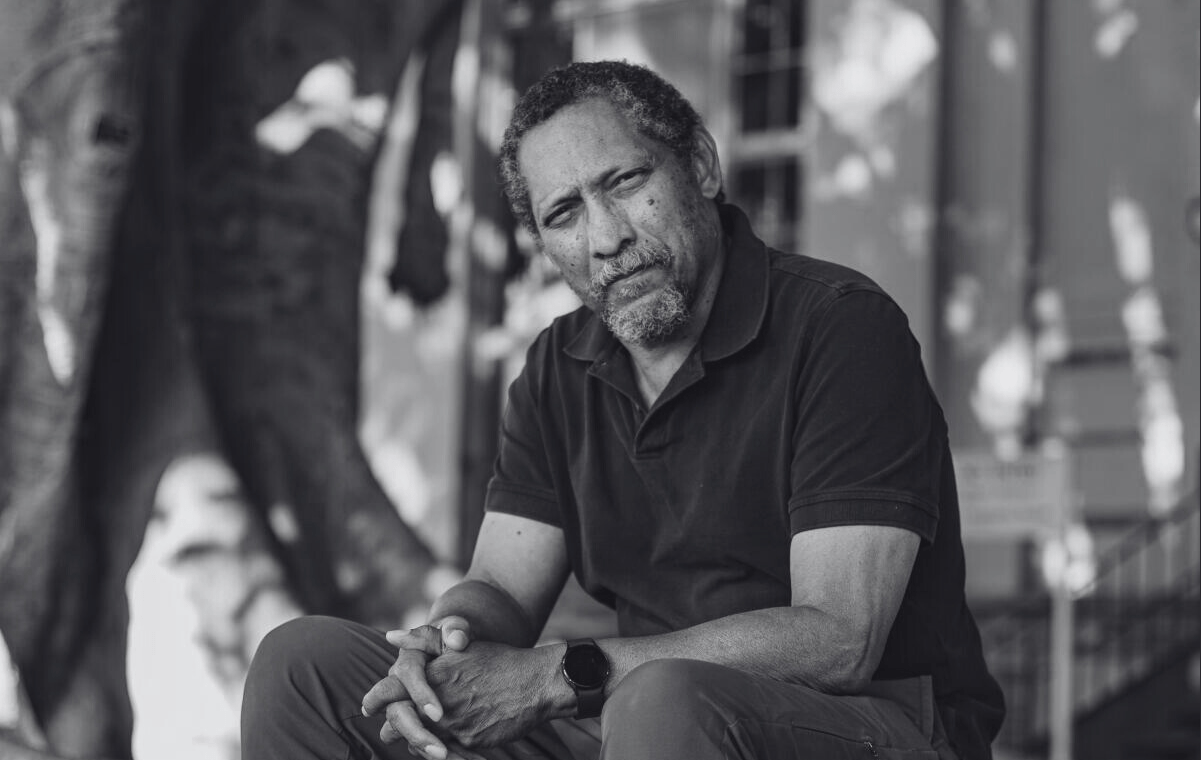

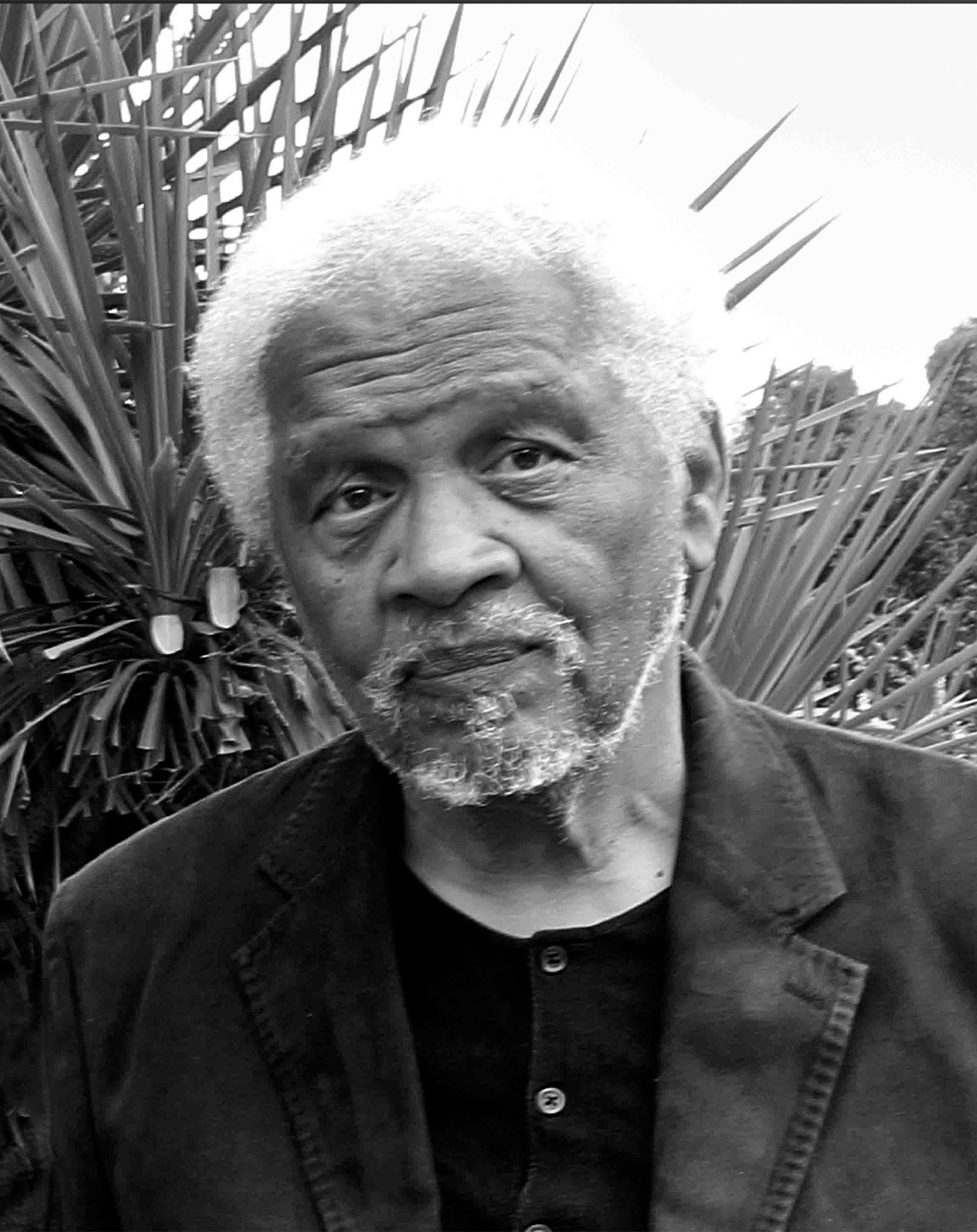

Percival Everett, a distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California and erstwhile cowboy, was at work on a novel, researching lynching, in the year before the pandemic began.

“The kernel of it was a song: Lyle Lovett, the country singer, covered the traditional song ‘Ain’t No More Cane’ and coupled it with another song called ‘I Rise Up,’” Everett told the Guardian. “I was listening to it before I played tennis one morning and I thought, huh, there’s my novel: what if everyone did ‘rise up.’ It became a kind of zombie idea, but I don’t like zombies, so it morphed into what it became.”

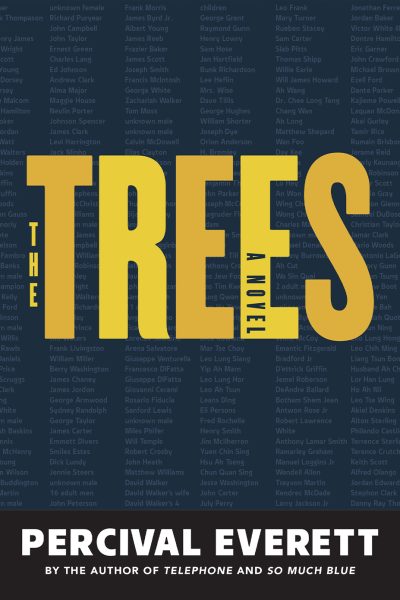

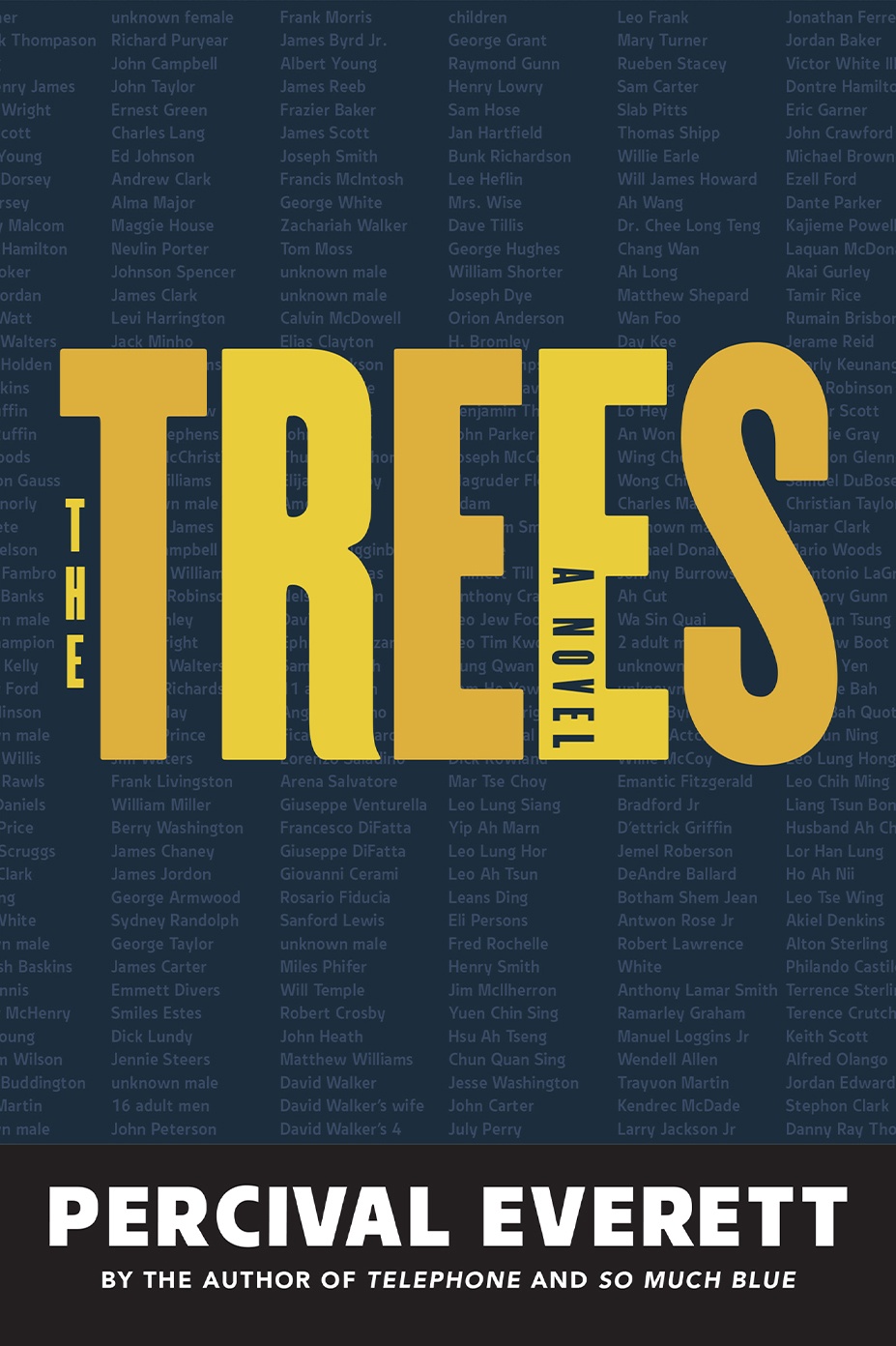

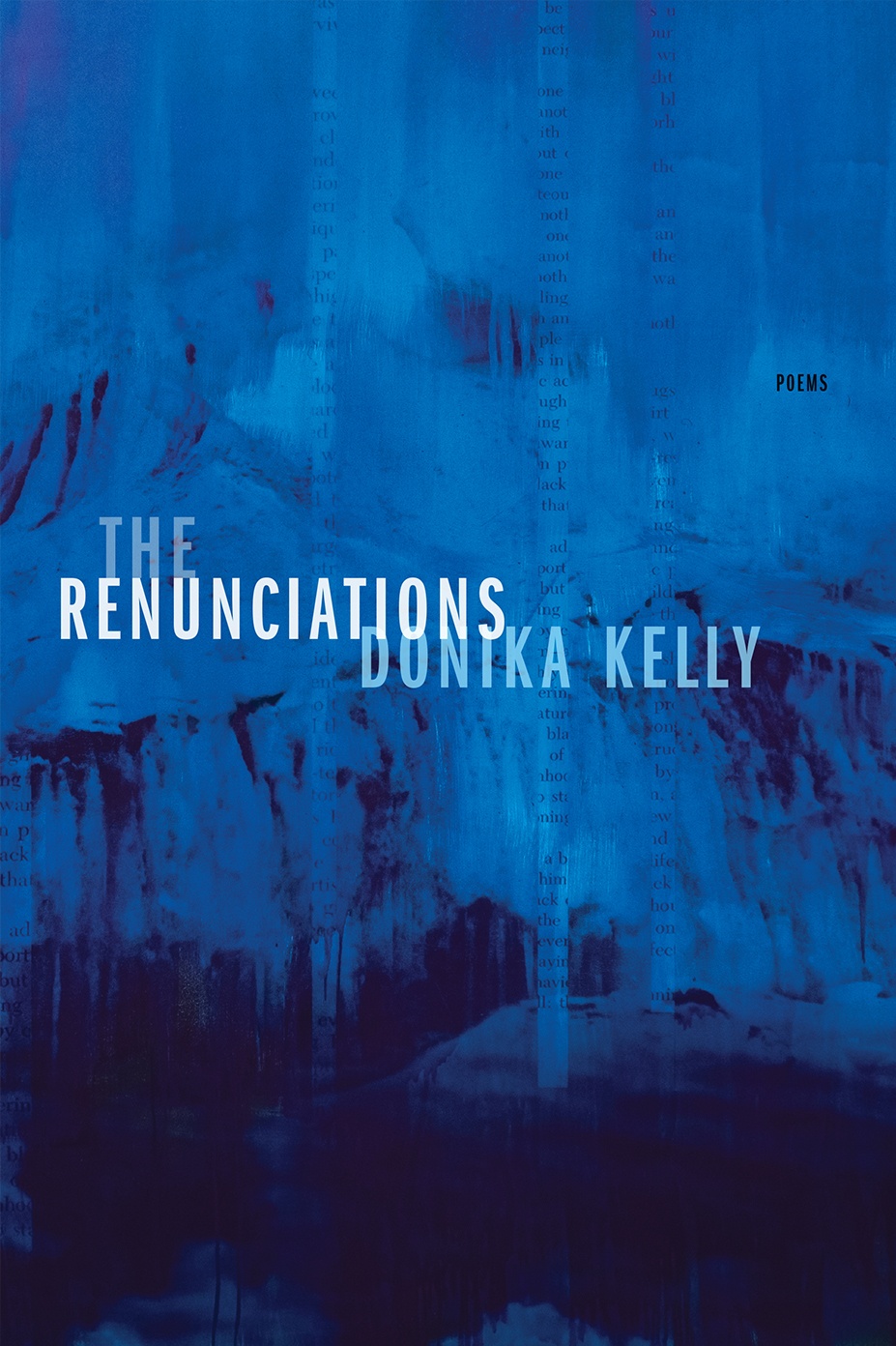

What it became, in the estimation of Anisfield-Wolf Juror Joyce Carol Oates, is a profound novel, “easily the most idiosyncratic, least classifiable work of fiction the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards has ever honored.”

Set in the present, “The Trees” opens as a comic caper story in downtrodden Money, Mississippi, where mutilated bodies start accumulating. At each crime scene is the corpse of a small dead Black man. The third to die is Granny C., a fictionalized version Carolyn Bryant Donham, the white woman who falsely accused Emmett Till of whistling at her in 1955. Her lie led to the boy’s lynching, and now, with the Black corpse beside her, she seems to have died of fright.

As two wise-cracking detectives wade into this murk, they realize the bonus corpse bears a striking resemblance to the body of 14-year-old Emmett Till. And now reports of other victims in other towns, sometimes accompanied by a dead Asian man, reach them. A crackerjack female FBI agent flies in. The short, addictive chapters deal out a “mixture of deadpan wit, slapstick accident and serious philosophical inquiry,” according to The New Yorker. Rita Dove, an Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards juror, said, “I was so dazzled I couldn’t turn the pages fast enough.”

Oates said, “This is a wickedly clever novel of ideas in the guise of genre fiction, a combination mystery, thriller, police procedural and absurdist comedy.”

The creator has two dozen books to his credit, including a 2021 Pulitzer finalist “Telephone.” Sometimes he chafes at their parsing.

“Apparently people need categories,” Everett told Yogita Goyal of the Los Angeles Review of Books. “I ignore them. . . I never speak to what my work might mean. If I could, I would write pamphlets instead of novels. And if I offered what the work means, I would be wrong. The work is smarter than I am. Art is smarter than us.”

Born in 1956 in Ft. Gordon, Georgia, Everett grew up with his sister Denise in Columbia, South Carolina, where his father Dr. Percival Leonard Everett practiced dentistry, and his mother, Dorothy Stinson Everett, worked alongside as his dental hygienist.

As a teenager, young Percival encountered the poet and novelist James Dickey, who was on faculty at the University of South Carolina. “I met him, as in I spent 15 minutes one day getting to talk to him,” Everett told the Los Angeles Review of Books. “And that meant a lot.”

The young Everett earned a degree in philosophy at the University of Miami, did ranch work for a decade, and took a master’s in writing at Brown University. He sometimes positions his fiction-writing as almost a side gig to fishing, training horses and mules, repairing mandolins and guitars, and raising his two children. He has said horses taught him to write.

“All these things refine different abilities to appreciate something,” Everett told James Yeh, review editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books. “If I’m hiking on a trail and I see a river, sometimes it’s just too beautiful and I can’t keep looking, so I have to glance at it and turn away. I have to admit it, that happens more with rivers than it does with art.”

Everett won the 2002 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for his best-known novel “Erasure,” and a PEN USA Literary Award for the novel “Wounded.” His 2020 novel “Telephone” came out with three separate versions. The Pulitzer board marveled at its narrative ingenuity.

“Seriousness without play is just dourness,” Everett told Yeh. “And real play is always serious. How much does a kid learn in a children’s game? Everything.”

Everett recounted being hired by the University of Southern California for Greil Marcus at Bookforum. “Someone who’s now a friend, a very close friend, when he saw my name – he’s kind of a prickly guy – said out loud to the office staff, ‘The last thing we need is another 50-year-old Brit.’ And the receptionist, who is a highly overqualified Black woman working as a receptionist said, ‘I’ll have you know he’s a Black cowboy.’”

Everett lives in Pasadena, California, with his wife, the novelist Danzy Senna.