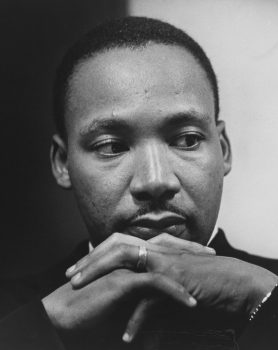

King was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, the eldest son of Martin Luther King Sr., a Baptist minister, and Alberta Williams King. King attended local segregated public schools, where he excelled. He entered nearby Morehouse College at age 15 and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in sociology in 1948. King Jr. was ordained as a Baptist minister at age 18. After graduating with honors from Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania in 1951, he went to Boston University, where he earned a doctoral degree in systematic theology in 1955.

Throughout his education, King was exposed to influences that related Christian theology to the struggles of oppressed peoples. In 1959 King visited India and worked out more clearly his understanding of Satyagraha, Gandhi’s principle of nonviolent persuasion, which King had determined to use as his main instrument of social protest.

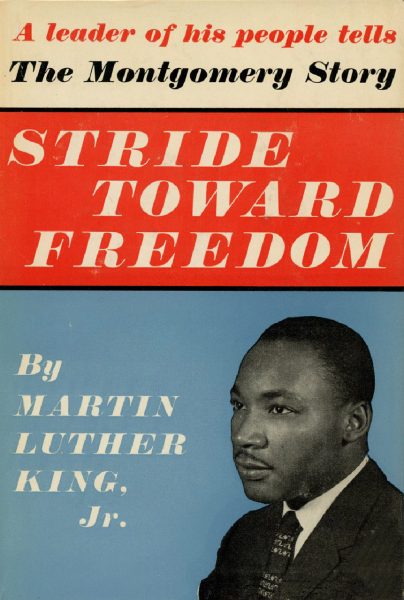

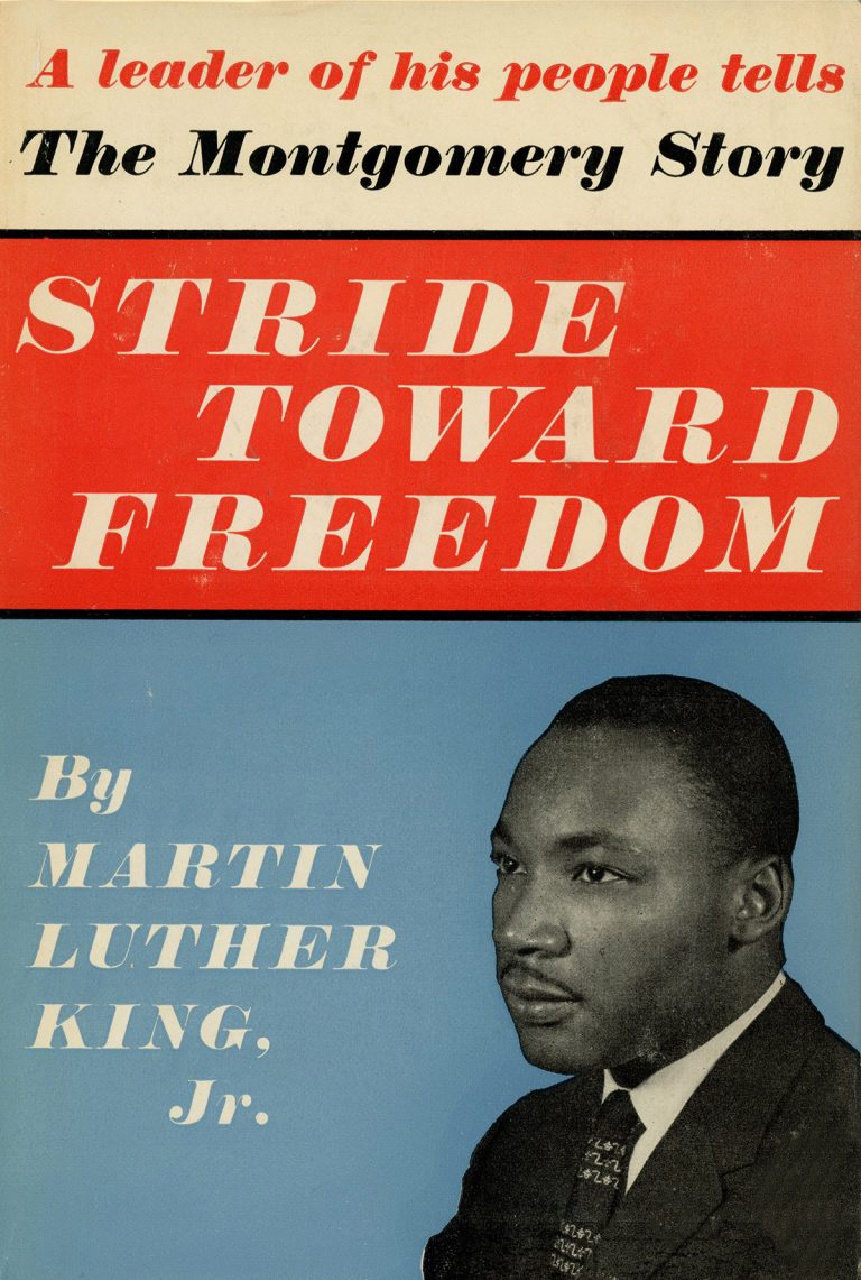

Soon after beginning a pastorate in Montgomery, AL, King was chosen as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), the organization that directed the bus boycott. King’s serious demeanor and consistent appeal to Christian brotherhood and American idealism made a positive impression on whites outside the South. His memoir of the bus boycott, Stride Toward Freedom (1958), provided a thoughtful account of that experience and further extended King’s national influence.

In 1957 King helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organization of black churches and ministers that aimed to challenge racial segregation. The SCLC encouraged the use of nonviolent direct action to protest discrimination. These activities included marches, demonstrations, and boycotts. The violent responses that direct action provoked from some whites eventually forced the federal government to confront the issues of injustice and racism in the South.

In the early 1960s King led the SCLC in a series of protest campaigns that gained national attention. In May 1963 King and his SCLC staff escalated anti-segregation marches in Birmingham. During the demonstrations, King was arrested and sent to jail. His “Letter from Birmingham City Jail,” written to local clergymen who had criticized him for creating disorder in the city, argued that individuals had the moral right and responsibility to disobey unjust laws.

King and other black leaders organized the 1963 March on Washington, a massive protest in Washington, D.C., for jobs and civil rights. On August 28, 1963, King delivered the keynote address to an audience of more than 200,000 civil rights supporters. His “I Have a Dream” speech expressed the hopes of the Civil Rights Movement in oratory as moving as any in American history: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’ … I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

As a result of King’s effectiveness as a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement and his highly visible moral stance, he was awarded the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. In 1965 the SCLC joined a voting-rights protest march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, more than 80 km (50 mi) away. The march created support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which President Lyndon Johnson signed into law in August.

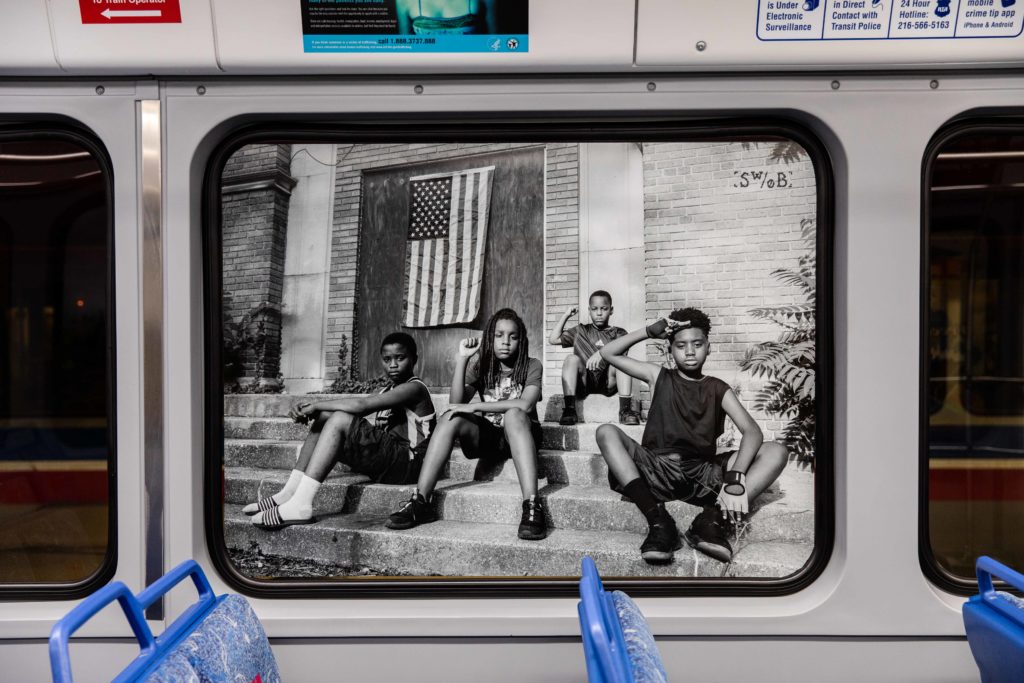

By the mid-1960s, King’s role as the unchallenged leader of the Civil Rights Movement was questioned by many younger blacks. Activists such as Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee argued that King’s nonviolent protest strategies and appeals to moral idealism were ultimately useless. Black Power advocates looked more to the beliefs of the recently assassinated black Muslim leader, Malcolm X. In addition, many white Americans who had supported his work believed that the job was done.

Throughout 1966 and 1967, King increasingly turned the focus of his civil rights activism throughout the country to economic issues. He began to argue for redistribution of the nation’s economic wealth to overcome entrenched black poverty. This emphasis on economic rights took King to Memphis, Tennessee, to support striking black garbage workers in the spring of 1968. He was assassinated in Memphis by a sniper on April 4.

After his death, King came to represent black courage and achievement, high moral leadership, and the ability of Americans to address and overcome racial divisions.