Shakyra Diaz, policy manager for the ACLU of Ohio, asked everyone in a crowded meeting hall who knew someone with a criminal conviction to raise a hand. Almost every person – mostly youth – lifted an arm overhead.

This was a respectable crowd – a City Club of Cleveland forum – and the arms aloft were eloquent. “The land of the free cannot be the land of the lock down,” Diaz said, and a junior at Gilmour Academy jotted the sentence in pencil on her program.

The note-taking at “A Conversation on Race” at the City Club youth forum was no accident. The urgency of police killings in Ferguson, Staten Island and Cleveland had drawn a crowd. Panelist and poet Basheer Jones challenged the hundreds of high school and college students assembled: “There is more we can do. Come prepared to write things down. You won’t remember everything said today. Teachers, have their students bring their weaponry. An African proverb says: ‘Do not build your shield on the battlefield.’”

Diaz and Jones were joined at the front of the room by Jonathan Gordon, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University, and Andres Gonzalez, police chief of the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority.

“Cops, we don’t always get it right,” said Gonzalez, the first Hispanic chief of police in the Northeast Ohio County. “That’s true….A police department is only as strong as the community allows it to be. When the community loses faith in the department that is almost the beginning of the end.”

Diaz zeroed in on system inequity: Cleveland is the fifth most segregated city in the United States; Ohio is sixth in its incarceration rate; fourth for incarcerating women. “This country is number one in the world for incarcerating adults and children,” she said.

Gordon brought forward Michelle Alexander’s groundbreaking book, “The New Jim Crow,” which examines a system that has now put more African Americans behind bars than there were slaves in 1850 before the Civil War. Jones stressed that the students in Collinwood and Glenville High Schools struggle in dilapidated buildings while the new juvenile detention center gleams like a “Taj Mahal.”

Metal detectors in schools condition students for prison, Diaz said, and schools that lack soap and toilet paper telegraph a lack of worth. All this connects, she said, to the Black Lives Matter movement.

When one student asked how to respond to those who claim they don’t see color, Diaz replied curtly: “That’s a lie. If you can see, you see color. What we shouldn’t do and cannot do is deny human dignity.” Echoing Ta’Nehisi Coates, who spoke at the City Club in August, Jones said, “The worst part about racism is that it creates self-hatred; some look in the mirror and don’t like what they see.”

Jones challenged the students to make sure their younger brothers knew more about the ABCs than Waka Flocka lyrics, more math than Usher. He stressed the importance of allies, noting that among the 30 Clevelanders he organized to go to Ferguson were Jews and Hispanics while “there are people in your community who look just like you who are working toward the destruction of it.”

Gordon underscored the importance of action, starting with the reformation of the Cleveland police department. He pointed to the good work of Facing History and Ourselves and the students at Shaker Heights High School who have battled racism. AutumnLily Faithwalker of Laurel School said she wished the panel, while strong, had focused more acutely on what exactly could be done.

Little is more urgent, Jones said. “If not addressed, these issues we are dealing with right now will be the downfall of our country.”

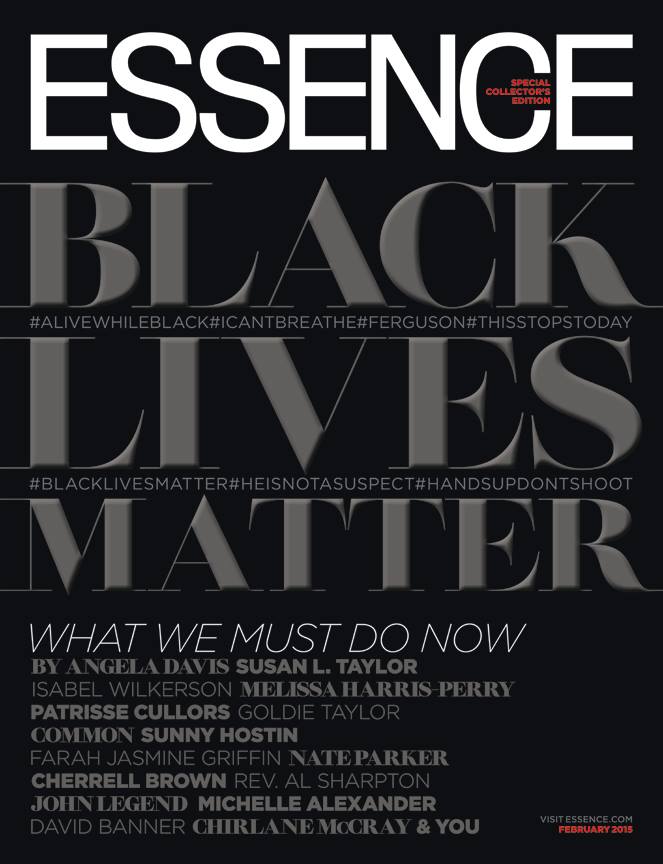

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.

Instead, the African-American publication has dedicated its February 2015 issue to “Black Lives Matter,” the social justice movement that has ignited in the wake of the killing of unarmed black people by law enforcement.

“Pictures are powerful, but so are words,” editor-in-chief Vanessa DeLuca writes in her Letter from the Editor. “After I spoke with the editorial team — with all our souls aching for answers — we knew immediately what we had to do: Tell the story of this tipping point in our history in America. So this February we are focusing our attention on the daring modern-day civil rights movement we are all bearing witness to and making a bold move of our own: a cover blackout.”

Instead, the magazine features essays from MSNBC host Melissa Harris-Perry, The New Jim Crow author Michelle Alexander and Isabel Wilkerson, author of The Warmth of Other Suns, which won an Anisfield-Wolf prize in 2011 for nonfiction.

“We must love ourselves even if — and perhaps especially if — others do not,” Wilkerson writes. “We must keep our faith even as we work to make our country live up to its creed. And we must know deep in our bones and in our hearts that if the ancestors could survive the Middle Passage, we can survive anything.”

This issue will be available on newsstands January 9.

In her influential best-seller, “The New Jim Crow,” law professor Michelle Alexander dissects the devastating racial consequences of “locking up and locking away” more than two million American citizens. And in her frequent public appearances, Alexander elaborates on the paradox of her subtitle: “Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.”

She drew a standing ovation on a recent, frigid night at Baldwin Wallace University near Cleveland. Speaking in a steady, clear voice, the Ohio State University professor delivered a portrait of contemporary racism difficult to hear: The U.S. prison population quadrupled in the last 30 years, fueled, Alexander argues, by a war on drugs applied disproportionately in communities of color. There are more American prisoners now than there were slaves in 1850 — before the Civil War. And black children now have less chance of being raised by two parents than black children born into slavery, a system notorious for dismantling families.

“We all know large numbers of black men are locked away in cages,” she told more than 800 listeners, some packed into an overflow room. “And we know people released from prison face a lifetime of discrimination, scorn and exclusion.” She listed some of the hundreds of work-required licenses barred for people with felonies — including in some states, a barber’s license.

“I now believe mass incarceration is the new Jim Crow,” said Alexander, 46, dressed plainly in a gray jacket, brown blouse and brown slacks. “People sometimes react with shock: What about Barack Obama? What about Oprah Winfrey? What about Colin Powell?”

The comedian Steve Colbert did, asking, with faux severity: “Why did not black people just say no?”

Alexander told him that solid research shows African Americans use illegal drugs at the same rates as other races, but are much more frequently prosecuted. She would like the country to return to its 1970s levels of incarceration, legalize marijuana, and end the war on drugs.

The American people twice elected a black president — a fact that Alexander believes helps mask a new system of racial caste, where nobody drinks at a segregating water fountain, but jobs, housing and food stamps are all blocked from those trying to re-enter society from prison. Poor communities are saddled with decrepit schools, while gleaming, high-tech prisons operate for profit. She cited the research of William Julius Wilson: in the 1970s, 70 percent of African-Americans in cities held blue-collar jobs; today the figure is 28 percent.

“The one thing that poor folk of color can ask for and get are police and prisons,” she said dryly. The daughter of the late John and Sandra Alexander, a senior vice president for ComNet Marketing group in Medford, Oregon, Michelle graduated from Vanderbilt and Stanford universities, and clerked for Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun. Her sister, Leslie Alexander, is a professor of African American studies at Ohio State University. Her husband, Carter Mitchell Stewart, is a U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Ohio.

Even as a civil rights lawyer, Alexander said she awoke to the new Jim Crow slowly, reluctantly: “There was a time when I rejected those comparisons out of hand as exaggerated and unproductive.”

No more. Her book won an NAACP Image award in 2011, and has been firing conversations in book clubs, churches and universities since it arrived in paperback. Some students at Baldwin Wallace took careful notes; others scrolled their smart phones. Partisans of the Communist Party sold newspapers at the door, and one man who identified himself as a lifelong member asked Alexander to declare her allegiances.

“I am someone who believes in justice,” she said carefully. “I am for basic human rights and economic justice for all. I resist labels and I am not going to assign one to myself.”

Her advice to students: “Think about movement building and not simply policy reform.” She pointed to the success of gay marriage advocates who bent public opinion: “Politicians have no choice but to respond.”

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.