In the onslaught of titles published each year, friends of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards can deploy a powerful technique to sift the wheat from the chaff: Find the new work from those writers already in the canon. Here are some gems sitting atop the 2019 pile:

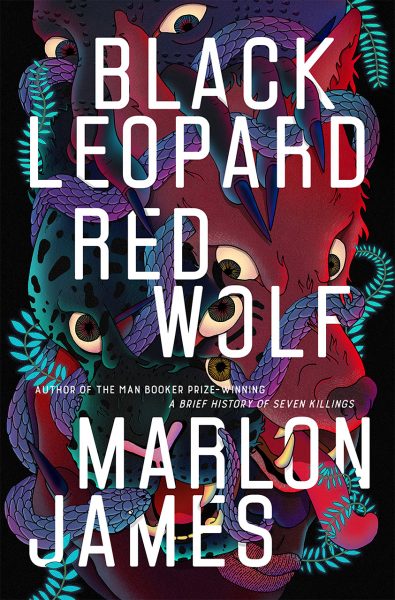

“Black Leopard Red Wolf” by Marlon James

The Jamaican American novelist most celebrated for “A Brief History of Seven Killings” goes genre. Actor Michael B. Jordan bought the film rights to this epic fueled by African mythology even before it published in February. The story — the first installment of a planned trilogy — spools out in beautiful sentences that coil around a hunter named Tracker. In nonlinear flashbacks, Tracker breaks his own rule of always working alone to find a disappeared boy, joining forces with a giant, a buffalo, a witch, a water goddess and a shape-shifting leopard. Following the child’s scent – Tracker “has a nose” – means trekking through forest, across rivers and through magical doors, beset by fantastical creatures. Tracker, we learn, is the red wolf of the title and the facts are murky. (“Truth changes shape as the crocodile eats away at the moon.”) This bloody quest-story is no escapism. As James told the New Yorker: “The African folktale is not your refuge from skepticism. It is not here to make things easy for you, to give you faith so you don’t have to think.”

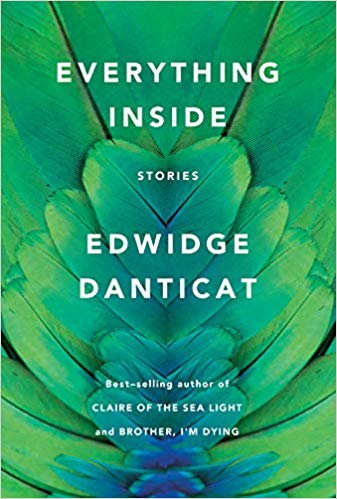

“Everything Inside: Stories” by Edwidge Danticat

The author of “Clare of the Sea Light” and “Brother, I’m Dying” brought out in August her first short fiction collection in more than a decade. Known for precise, pitch-perfect sentences and a gift for juxtaposition, Danticat weaves eight Haiti-influenced stories of diaspora and longing. She pairs Cindy Jimenez-Vera’s insight — “being born is the first exile” — with Nikki Giovanni’s “We love because it’s the only true adventure” to frame the urgencies of quiet lives. One belongs to Elsie, a Miami home-health care worker, whose decency is no match to the manipulations of her ex-husband and former best friend. Another centers on a New York City teacher who is cheated of a final chance to meet her father before his late-life death. The last story, “Without Inspection,” covers 6.5 seconds as a construction worker falls toward oblivion. He realizes that “whatever he wanted he could have, except what he wanted most of all, which was not to die.”

“The Gilded Auction Block” by Shane McCrae

Following his essential poetry collection “In the Language of My Captors,” McCrae continues his investigation of U.S. freedom and its contradictions. In 23 poems, McCrae addresses the present American moment, and in some pieces responds directly to Donald Trump. The first poem, “The President Visits the Storm” starts with an epigraph from the 45th chief executive: “What a crowd! What a turnout!” — proclaimed to victims of Hurricane Harvey. And McCrae considers how the country has turned out. A poem titled “Black Joe Arpaio” begins “America you wouldn’t pardon me.” In another, McCrae stands up the exact language Carrie Kinsey used in a 1903 letter to Theodore Roosevelt about her brother – wrongly sold into forced labor – and transforms it through ear and syntax into a searing work of art. The poet also circles back to his white supremacist grandmother in Texas “who loved me and hated everybody like me.” She and her black grandson create a knot that grief cannot untie. It is a privilege to read his reckonings now.

“Grand Union” by Zadie Smith

The outlandishly gifted British novelist of “White Teeth” and “On Beauty” published her first short story collection in October. In 19 tales, she wheels through a dizzying constellation of topics, tones and fonts, writing about the future and the past. A reader can enter anywhere, like her bravura “The Lazy River,” an endlessly rotating watery amusement for tourists in Spain. Elsewhere, the writer spills blood in London even as the jaunty “Escape from New York” rifts on the urban legend that Michael Jackson ferried Liz Taylor and Marlon Brando out of the smoking debris of 9/11 in a rental car. And the marvelous “Words and Music” mediates on peak musical experiences as lived by two disputatious sisters. A couple of stories are closer to fragments, but several seem destined to become classics. Smith begins and ends with two mother-daughter stories — the first bristles with alienation, the last, “Grand Union” with the transcendence of generations.

“I: New and Selected Poems” by Toi Derricotte

The Pittsburgh poet co-founded Cave Canem, whose motto is “a home for black poetry.” This collection serves as a profound home for 30 new pieces as well as those swept from five earlier books across a span of 50 years. The title “I” comes from Derricotte’s son and is perfect for a writer sometimes characterized as a confessional poet, one who has mined the self to grapple with gender, race, identity, sex and spirit. In “Tender” she writes: “The tenderest meat/comes from the houses/where you hear the least/squealing. The secret/is to give a little wine before killing.” The collection, dedicated in part to “the mother and fathers – Galway, Lucille, Ruth and Audre” gestures toward the poetic ancestry of Galway Kinnell, Lucille Clifton (another Anisfield-Wolf recipient), Ruth Stone and Audre Lorde. In her acknowledgements, Derricotte writes, “I am most grateful to the universe for the community of Cave Canem. We imagined a place in which black folks were safe to write the poems they needed to write.” And so she has.

“A Long Petal of the Sea” by Isabel Allende

The beloved novelist, born in Peru, raised in Chile and now a resident of northern California, writes in her acknowledgements: “This book wrote itself, as if it had been dictated to me.” Indeed, this historical fiction contains unmistakable autobiographical notes. It begins with the Republicans loss of Spain and the marriage of convenience between fighters Victor Dalmau and Roser Bruguera in 1938. She is pregnant with the son of his slain brother and can only leave France aboard a ship for wounded fighters if she marries him. The ship sails to Chile and their bond of expediency begins a complicated family saga that crests with the catastrophic 1973 overthrow of the democratically-elected Chilean government, just as it radically altered the author’s life. Allende knows how to spin an engrossing story and to reward her readers with a savory and satisfying surprise for the 80-year-old Victor at the end.

“The Nickel Boys” by Colson Whitehead

The arrival of this latest novel from “The Underground Railroad” writer caused Time Magazine to enshrine him in July as “America’s Storyteller.” Seventeen years earlier, Whitehead picked up an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for “John Henry Days.” The novelist returns to U.S. history for “The Nickel Boys.” It is based on a Florida reform school, the Dozier School for Boys, that warped the lives of thousands of children for 111 years. In the fictional treatment, Elwood Curtis is derailed from his path toward college and pitched into a facility where “all the violent offenders . . . were on the staff.” Turner is wiser to the rigged game and eats soap when forced labor becomes unbearable. Whitehead doesn’t dwell in horror, instead, pervasive racism soaks the novel’s ground, so there is nowhere to stand for either boy. In prose as clear as water, Whitehead traps his reader. Undergirding it all are the unmarked graves of close to 100 Dozier boys unearthed in 2014. Finally made unforgettable.

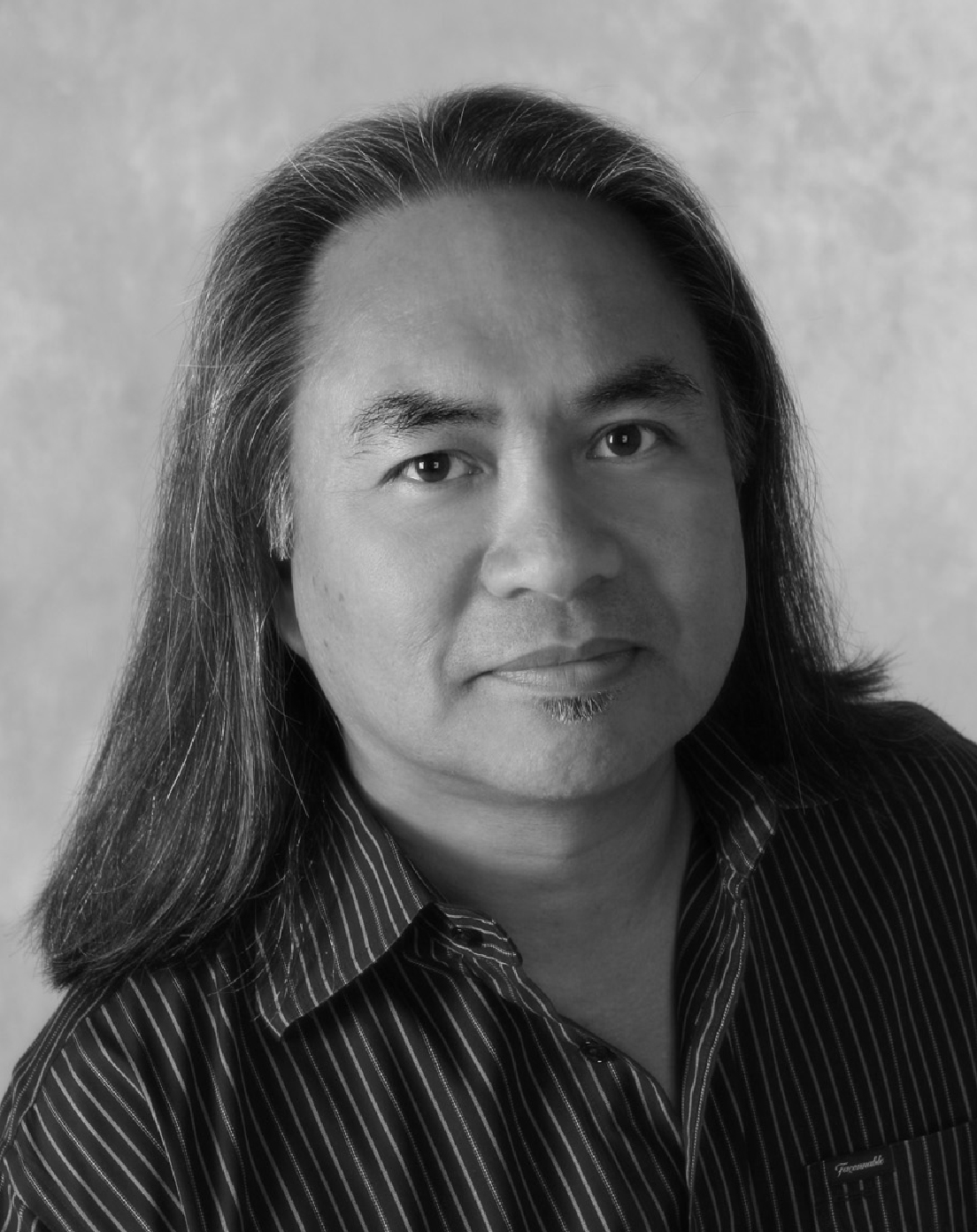

“Sightseer in This Killing City” by Eugene Gloria

This is Gloria’s first book since the Manila-born Midwestern poet won his Anisfield-Wolf prize for “My Favorite Warlord” in 2013. Known for taking months, and sometimes years, on a single poem, Gloria joins Shane McCrae in pondering the contemporary American moment. Deeply attuned to heritage and displacement, the new poems continue Gloria’s preoccupation with the arrivals and departures of ordinary people. The title poem reverberates from a Dallas hospital. The other 47 in this collection are concise, erudite and plain-spoken in language enriched by Gloria’s reading across continents and centuries. He samples Stevie Wonder and Shakespeare; Baudelaire and Al Green. In “Implicit Body,” the speaker commands “Call me Mr. Gone/who’s done made/some other plans./All that remains is nostalgia/and this aching torso of blue.”

“The Tradition” by Jericho Brown

Named to several best-of-the-year lists, this stunning collection grapples with the black body, especially the queer black body, in poems that combine bright music and “everything cut down.” Brown follows his “The New Testament,” which won an Anisfield-Wolf prize, with a meditation over 51 poems on masculinity, desire, violence and tradition: in poetry, in racism, even in the impulse to plant gardens. In the musical, compressed lines of “Dark,” Brown writes “I’m sick/of your hurting. I see that/you’re blue. You may be ugly/but that ain’t new.” The poet comes up with a new form, “the duplex,” which he designed to gut the sonnet. “The Tradition” is suffused with prickling self-knowledge, of a sense of this poet coming into his own. He addresses his own persona in “The Rabbits”: “I am tired/Of claiming beauty where/There is only truth.”

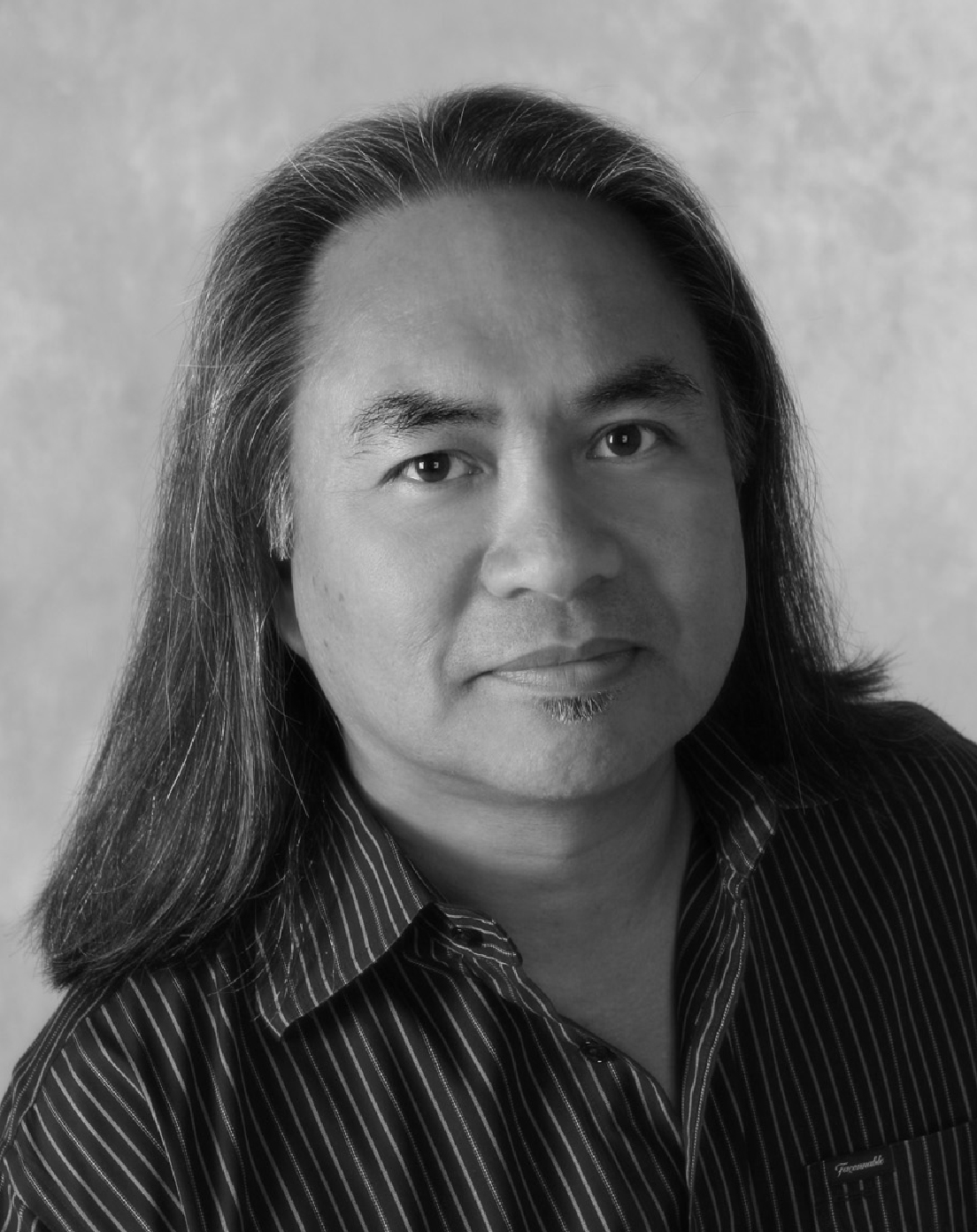

Readers of Eugene Gloria’s poems have a cultivated patience, a relationship with time. It has been seven years since the publication of his last book, “My Favorite Warlord,” winner of an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.

In 2013, Henry Louis Gates Jr. praised Gloria’s poetry by remarking on his own keen interest in genealogy. The Anisfield-Wolf jury chair located a kinship in the poet’s exploration of our origins “as a key to the present [that] is compelling, addictive, and – in the best circumstances – generative. It is this last quality that is evident on every page.”

Gloria, 62, is deeply attuned to heritage and displacement. Arrivals and departures cycle through all four of his considered, beautiful and nimble poetry collections.

“My Favorite Warlord” opens with “Water,” a 39-line poem that took Gloria five years to write. Reading it now, it seems to flow toward the new book, “Sightseer in This Killing City.” The poet Yusef Komunyakaa identified “a playful exactness” in Gloria’s first collection, “Drivers at the Short-Time Motel,” which remains just right describing this new work.

The speaker of the title poem, “Sightseer in This Killing City” is in Dallas:

When I arrived, I saw the grassy knoll

Down that killing square. My cousin sick

and so I came with only Roethke’s line:

‘On things asleep, no balm.”

This poem may be set in Texas, but the book’s sensibility is informed by the troubling ascendancies of Philippines President Rodrigo Duarte and the U.S. President Donald Trump, both elected in 2016. The title poem ends, “And tomorrow is the past,/a gurney’s wheels squeaking/dry and violent through contagious halls.”

Democracies in the hospital, perhaps, the world a place of contagion, which “smiles wide as elevator doors.” The dis-ease is clearly infectious, leaving the reader, like a voter, to puzzle this out.

Gloria, born in Manila as his parents’ youngest child, grew up on both sides of the Pacific Ocean after his family settled in San Francisco. He has traveled widely but has lived mostly in the Midwest, the last two decades as a professor at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana.

In the 48 poems of “Sightseer in This Killing City,” there is an exquisite, erudite, yet plain-spoken care with language from a poet well-read across continents and centuries. Snippets of verse from William Shakespeare and Charles Baudelaire crop up; so does a line from an Al Green song.

Anisfield-Wolf winning poet Marilyn Chin observes that Gloria’s new book tells unsettling stories “that praise ordinary people.” This is exactly right, including people on buses and those waiting in terminals. Poet Rigoberto Gonzalez calls the experience “a blessing to have Eugene Gloria help us reckon with the troubles histories that shape America [and] the Philippines.”

The new collection’s first poem, “Implicit Body,” ends stunningly by re-purposing a rift from a Stevie Wonder song. Gloria writes: “Call me Mr. Gone / who’s done made / some other plans./All that remains is nostalgia/and this aching torso of blue.”

One innovation is a persona Gloria calls Nacirema. The poet explains that the name “comes from artist Michael Arcega’s clever use of nomenclature as a way of examining Filipino American identity as well as his repurposing of Horace Miner’s essay ‘Body Ritual Among the Nacirema,’ from American Anthropologist, 1956.

The issue of the magazine published a few months before little Eugene was born in the capital city. It is a continuing pleasure to dwell in the worlds, and work, that child has wrought.

Tom Pantic, a junior at Hiram College in Ohio, wanted to know how poet Eugene Gloria felt about being put in the Asian box.

Gloria, known for his nuanced poems exploring identity, geography and masculinity, took a moment in the college’s wood-paneled Alumni Heritage Room to gather his thoughts on a complicated question.

“I’m OK with being grouped with Asian American poets – I’m very proud of that community,” he said. “It is a problem to be put on the ethnic shelf, with ‘American poets’ shelved elsewhere – that’s a problem for me. I’m happy to represent. I’m a Filipino poet but there are many other identities I inhabit.”

Gloria, now 58, was the youngest of six children when his family left Manila and settled in San Francisco. The first poem in “My Favorite Warlord” is called “Water.” It begins:

The street when I was five

was a deep, wide river

coursing through a shimmering city.

I had no need for proper shoes,

no need for long pants.

I didn’t yet know how to make

Conclusions and say, “Life’s like this . . .”

Gloria, who won a 2013 Anisfield-Wolf Book award for “My Favorite Warlord,” read “Water” several times over three days in Hiram. He visited high school students, ate dinner with English majors and gave a warm, wry public appearance, part of a Big Read initiative this fall in Hiram. “It took me five or six years to finish ‘Water,’” he told those gathering in what was once the college library.

“The students from both local high schools and Hiram College . . . came away with a new understanding of the power of poetry to convey deep emotions, to comment on social issues, or just to crystallize a moment in time,” noted Gloria’s host, Professor Kirsten L. Parkinson, who directs the Lindsay-Crane Center for Writing and Literature at the college.

As he answered Pantic, Gloria made a glancing reference to the eruption this year over the Best American Poetry Anthology, in which a white Midwestern archivist named Michael Derrick Hudson submitted a poem under the false name Yi-Fen Chou to increase his odds of being selected. The subterfuge succeeded and provoked blistering criticism.

“How unfortunate to think I have an ‘in’ because my name is exotic enough,” Gloria in an interview said after his reading. “Mostly I feel sad. This is another instance of – racism is probably too strong – of misperception. Poetry is an opportunity for me to be honest about my identity. I like what [anthology editor] Sherman Alexie called it, ‘colonial theft.’ ”

Alexie made the controversial decision to keep Hudson’s poem in the 2015 anthology; Gloria plans to incorporate this episode into the discussion of the creative writing workshop he leads at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana.

“I like to go to Indianapolis occasionally to take care of my Asian needs – fish sauce, good rice,” Gloria riffed in his gentle, mellifluous voice. He then read “Here, On Earth,” adding, “yes, happy poems are possible.”

The October evening in Hiram served as a welcome tour of “My Favorite Warlord” with Gloria providing insights into individual poems. He began the book sparked by an observation from Susan Orleans, who suggested that boys of 10 define the man they will become at 40. Gloria realized that at 10 he was a schoolboy at St. Agnes Elementary School in the Haight Asbury neighborhood in 1967, a fascinating spot in a momentous year. So he began writing poems constellated around 1967, but as he worked, “My Favorite Warlord” developed a parallel meditation on Gloria’s father, inflected with an interest in the 16th century Japanese warrior Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

“It became an accidental book in that I was conflating my thoughts about Hideyoshi with meditations on my father,” Gloria told a DePauw University staff writer. “People assume that ‘my favorite warlord’ is my father, which really isn’t the case. But I don’t mind the mistake, because on some level I was thinking about both of them as one thing.”

For his part, Pantic loved the poem “Allegory of the Laundromat,” also a favorite of Anisfield-Wolf Jury Chair Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Pantic quoted the final line in his introduction of Gloria:

Who gives a whit about the indelicate balance of our weekly wash?

Eugene Gloria‘s My Favorite Warlord earned praise from the Anisfield-Wolf jury for his “vivid and striking” work examining masculinity, identity, and heritage. His 2012 collection of poetry helped him snag his latest literary prize, the 2013 Anisfield-Wolf award for poetry. Prior to this year’s ceremony, we talked to Gloria about what winning the award meant to him and where he sees his career headed next.

Eugene Gloria On Winning A 2013 Anisfield-Wolf Award For Poetry from Anisfield Wolf on Vimeo.

Eugene Gloria says that he is fascinated by failure. He was quick to describe a particular poem or two as failed, and even his book, “My Favorite Warlord,” which won a 2013 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, as a failure of his original idea to describe 1967.

“I ran out of ideas for 1967, became bored,” Gloria told listeners at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland. “I ran out of gas, even though I was obsessed by it. The idea of failure is fascinating to me.”

And yet, 1967 is a fulcrum in “My Favorite Warlord” – the year his family arrived in San Francisco from the Philippines, the year his future wife was born in Detroit, the year that Wole Soyinka is “being hauled to jail/on trumped-up charges” as Gloria writes in “Allegory of the Laundromat.” He told the MOCA audience that he was thinking about soul music as he wrote it.

Harvard University’s Henry Louis Gates, Jr., praised this very poem as he introduced Gloria to the sold-out audience gathered at the Ohio Theatre Sept. 12 for the Anisfield-Wolf awards ceremony:

“What I find so resonant in all of these poems is the idea of multiplicity, that we possess many identities stemming from the many diverse forces that have shaped us,” Gates said. “In Gloria’s case, he is shaped by a Filipino background, though education among the nuns in a Catholic school, to coming of age in the same neighborhood in which he found ‘Janis Joplin shoring up supplies/from our corner Chinese grocer.’”

Gloria, 56, has taught for 13 years at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. He read his poem, “Here, On Earth” for both the crowd at MOCA and the throng at the Ohio Theatre. He told his listeners that it captures his relationship to Indianapolis. The final two stanzas:

Here, on earth we are curtained by rain.

A subset in the far corners floating

toward the center. We are an island

in landlocked America. We are

Thai, Filipino, and Vietnamese.

We are, all of us, post exotics.

At MOCA, Gloria followed a reading from Kazim Ali, an Oberlin College professor who started with his poem “Fairytale.” It concludes, “All the sacred words/are like birds wheeling in the sky./Who knows where they go?” The political nature of Ali’s reading inspired Gloria to start with “Elegy with Ice and a Leaky Faucet.” He called it “one of the oddball poems in my collection; it failed as a political poem.”

And yet “Elegy with Ice and a Leaky Faucet” is many reader’s introduction to Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American man beaten to death on the eve of his wedding by Detroit auto-workers enraged at the ascendancy of Japanese cars in the U.S. market. “The dialectics of fists and ball bats/turned his wedding party into a funeral” Gloria writes.

When Ali and Gloria perched on tall stools together at MOCA, Ali spoke about the context for two of his newest poems, which focus on Bradley Manning, convicted in July for violating the U.S. Espionage Act.

“We are political,” Ali said. “We can notice it or not notice it.”

“Amen to that brother,” Gloria responded. “We try to avoid being cliché. The struggle is taking an overt political position in an art that calls so much attention to language can be problematic. But like Kazim says, we are all political.”

The men riffed on Shelley’s famous maxim that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” suggesting that the “unacknowledged legislators of the world” may well be the secret police.

Before he returned to Indiana, Gloria said, “The idea of identity is always going to be a subject. I have no choice. Identity is so multi-layered and I am obsessed.”

by Kathleen Cerveny

My Favorite Warlord, by Eugene Gloria, is the recipient of the 2013 Anisfield Wolf Book Award for Poetry. This award, administered by the Cleveland Foundation, recognizes books that have made important contributions to our understanding of racism and our appreciation of the rich diversity of human cultures. Now in its 78th year, the Award is juried independently by a panel of scholars led by Dr. Henry Louis Gates.

In this, his third book of poetry, Eugene Gloria continues his focus on his cultural origins in the Philippines. He offers poems that range between accessibility and a satisfyingly complex look at the experiences of Asians growing up in America; he examines family and home — both here and far away — and identity and belonging. From his time growing up in San Francisco and Detroit, Gloria places these issues in the context of an America familiar to us all. At the same time, he invites us to learn something of Asian culture through the use of poetic idioms and historic references that often require thought and close reading.

The book’s many-layered but quite approachable title poem is an example of this. It references Kurt Cobain, the elegance of the zen garden, and historic figures from ancient Japan and 20th century Portugal, in describing the poet’s difficult relationship with his father; “an irascible manager” whose presence pervades the book.

The poem’s opening epigram; “Hello, hello, hello …” from the grunge band, Nirvana’s iconic song, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” suggests this will be a poem of alienation. Indeed, not three lines in, Gloria’s narrator says “hello” silently to his father watering the flowers in his garden, as he drives past his aging parent’s home — without stopping. In 24 short lines, Gloria gives us a deeply layered, cross-cultural and completely real portrait of the difficult relationship between a father, who cannot change the dominating legacy of his cultural heritage, and a son who has taken another path.

Indeed, as the title poem suggests, the relationship with the father is a central theme in the book. A group of six poems, “Photographs With Images of My Father,” sensitively explores aspects of the father’s life and personality through the use of different poetic forms.

Throughout the book, Gloria mixes free verse with ancient poetic forms from Asia – haibun and pantoums. There are elegies, allegories, and psalms, references to the eastern religions of his cultural heritage and the Catholicism of his own upbringing. Although some readers may need Google on hand to understand all the references, it is an effort worth making.

Indeed, one poem, “Cogon,” a haibun, still has me wondering. Cogon is a tall, coarse grass used by villagers of the tropics to thatch roofs. Cogon Shrine is a Catholic church in Manila. Both of these may, in some way, relate to the poet’s Philippine heritage. However, how the title relates to the prose section of the haibun about men lost to the seduction of the “daughter of the mountain” eludes me, even after research.

My Favorite Warlord is a journey in memory, progressing in time through the four sections of the book. Although not titled, one might name them; Assimilation, Awareness, Identity and The Poet Confronts His Gift. These are rich, poignant expressions of the challenges of an Asian family’s efforts to fit into American society. From “Here, On Earth”

Here, on earth we are curtained by rain.

A subset in the far corners floating

toward the center. We are an island

in landlocked America. We are

Thai, Filipino, and Vietnamese.

We are, all of us, post exotics. (34-39)

and from “Monsoon Season”:

… I was seven that monsoon season

before the highway had a proper name

before my father became a U.S. citizen

and shortened his name to Sid. (6-9)

Gloria’s poems explore the exhilaration and danger of freedom in America’s “summer of love” and confront us with the prejudice and brutality that continues to this time, by those considered ‘other.’ We find tender personal stories of family set against the horrors of war, the burning of monks and astronauts. There is the near rape of a sister, the ‘honor killing’ of a young girl by her brothers, the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese man beaten to death in Detroit by two American auto workers angered by Japan’s impact on the auto industry.

In the final section of the book, Gloria, like many poets before him, questions his own gifts. From “Trees As Soldiers March:”

There are other circles of hell reserved

For other margin-huggers like me

Despite all those statues weeping blood,

Praying their thousand, thousand mighty prayers.

The beauty of my god is allowing me to suffer

While I invoke his name daily through the small

Disasters I make with my own hands. (20-26)

These final poems, in a way bring us back to Cobain who, in “Smells Like Teen Spirit” states:

I’m worst at what I do best

And for this gift I feel blessed.

Eugene Gloria’s gift is to bring us elegiac and sensitive encounters with the cultural experience of the growing number of Asian ‘others’ in our increasingly multi-cultural America.

Kathleen Cerveny has been a working artist, educator, development officer, and award-winning producer of arts programming for Cleveland Public Radio. She is also the Cleveland Foundation’s director of arts initiatives where, for two decades she has directed its arts and culture programs and led major initiatives in public policy and organizational advancement for the arts.

Kathleen Cerveny has been a working artist, educator, development officer, and award-winning producer of arts programming for Cleveland Public Radio. She is also the Cleveland Foundation’s director of arts initiatives where, for two decades she has directed its arts and culture programs and led major initiatives in public policy and organizational advancement for the arts.

Kathleen is completing a Master’s degree in poetry through the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Creative Writing Program. She is a published poet and held the title of Cleveland’s Haiku Champion from 2009-2011 and currently (2013-14) is the Poet Laureate of the City of Cleveland Heights.

Eugene Gloria’s 2012 poetry collection, My Favorite Warlord, won this year’s Anisfield-Wolf prize for poetry. Born in Manila, Phillippines, Gloria uses My Favorite Warlord’s 35 poems to explore Filipino heritage, samurai, fathers, masculinity, and memory.

Eugene Gloria’s 2012 poetry collection, My Favorite Warlord, won this year’s Anisfield-Wolf prize for poetry. Born in Manila, Phillippines, Gloria uses My Favorite Warlord’s 35 poems to explore Filipino heritage, samurai, fathers, masculinity, and memory.

Publishers Weekly praised the work, noting that Gloria “sets himself confidently against injustice, in favor of inquiry, amid the eclectic language of contemporary scenes.”

Gloria has written two other books of poems—Hoodlum Bird (2006) and Drivers at the Short-Time Motel (2000). His honors and awards include an Asian American Literary Award, a Fulbright Research Grant, a San Francisco Art Commission grant, a Poetry Society of America award, and a Pushcart Prize. He teaches creative writing and English literature at DePauw University.

The jury has spoken and five new authors will join the Anisfield-Wolf family.

Our 2013 winners are:

“The 2013 Anisfield-Wolf winners are exemplars who broaden our vision of race and diversity,” said Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who chairs the jury. “This year, there is exceptional writing about the war in Iraq, slavery on a Kentucky pig farm, the Filipino experience in the U.S., and the complexity of families in which a child is radically different from parents.”

Gates directs the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research at Harvard University, where he is also the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor. He praised the singular achievement of Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian whose writing won a Nobel prize in 1986, three years after he won an Anisfield-Wolf award for his memoir, Ake: The Years of Childhood.

Cleveland Foundation President and Chief Executive Officer Ronald B. Richard said this year’s winners reflect founder Edith Anisfield Wolf’s belief in the unifying power of the written word.

“The Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards rose from the philanthropic vision of one woman who realized that literature could advance the ongoing dialogue about race, culture, ethnicity, and our shared humanity,” Richard said.

The Anisfield-Wolf winners will be honored in Cleveland Sept. 12 at a ceremony at the Ohio Theatre hosted by the Cleveland Foundation and emceed by Jury Chair Gates. Stay tuned this week as we profile each of our 2013 winners.