by Elysia Balavage

Whether visible or invisible, emotional or physical, trauma is an inescapable component of human existence. The ways that individuals reclaim and remake a traumatic experience form some of the most rousing narratives.

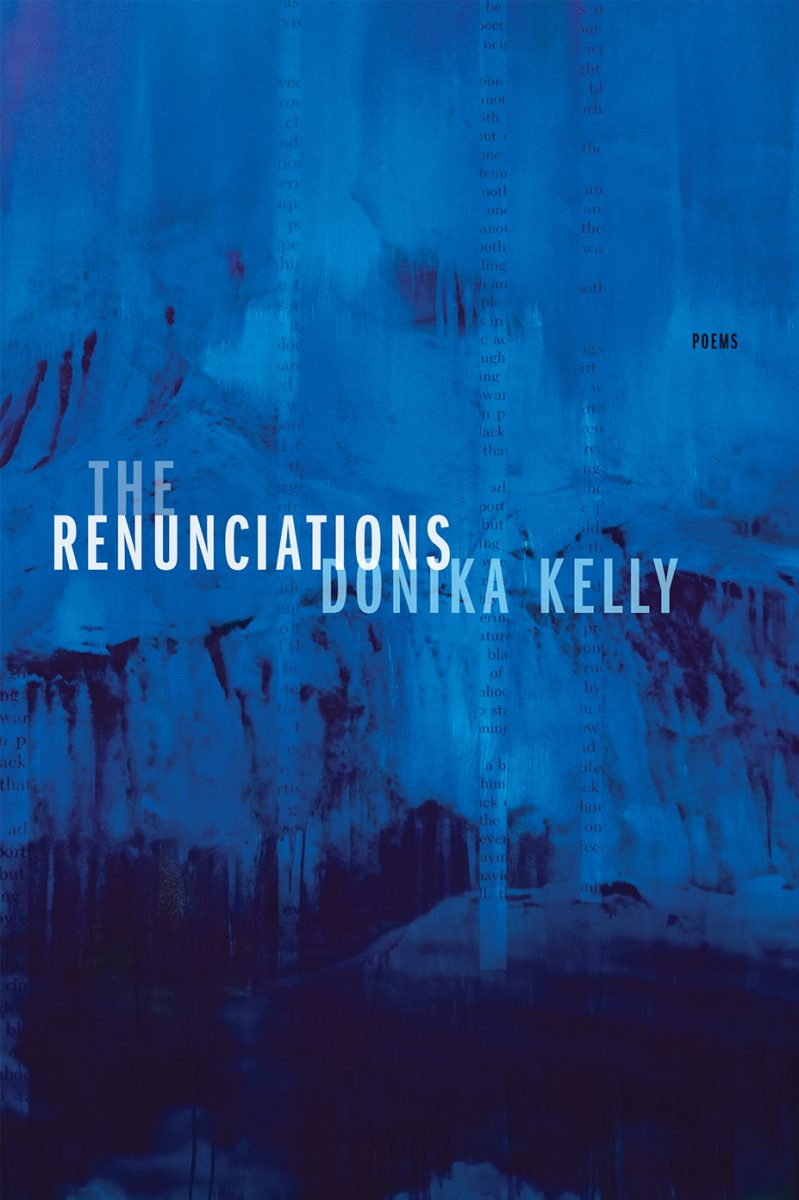

Donika Kelly’s confrontation with personal trauma—the speaker’s sexual abuse at the hands of her father—in The Renunciations is simultaneously raw and refined as she mixes visceral content with a sophisticated, technical use of form.

When teaching my course on social justice and the human condition, I include poems from The Renunciations in a unit titled “The (In)Visible” alongside works by Gwendolyn Brooks, Ralph Ellison, Ama Anima Nuamah, and Nell Dunn. Each of these authors confronts trauma— intergenerational, systemic, and private—with an unwavering refusal to be rendered silent and invisible. As the title suggests, Kelly narrates an official, ongoing relinquishing of private trauma as the volume unfolds. What really intrigues my students, however, is the way that “renunciation” acts as a recurring rhetorical negation. Simply put, the act of “renouncing” tills a space for growth and overcoming.

I begin each class meeting with a question of definition. Specifically, I ask students to define an amorphous, abstract concept—beauty, justice, power—using concrete, detailed language. This is more challenging than it sounds because we often use these words every day without pausing to consider what they entail.

When introducing The Renunciations, I ask “What does it mean to renounce?” My students’ responses are always thoughtful, with many of them highlighting the “wilful” and “conscious” connotations of the word. With their definitions of “renounce” in mind, students can more effectively observe this theme’s development across the volume.

Kelly utilizes the deliberate, self-aware act of “renunciation” most clearly in the “Dear—” poems that begin five of the volume’s six sections. Here, her stylistic and metaphorical use of redaction—literal blackened out lines of text—puzzle my students at first, but their curiosity about this rhetorical choice yields fruitful class discussions. The redactions are physically and visually imposing on the page, comprising most of these “Dear—” poems’ content to such an extent that only a few words of readable text remain.

However, the redactions are empowering in themselves as the speaker strikes out the words, lines, and traumas that do not serve her. Fascinated that negation can yield an overcoming, my students appreciate that these poems also represent the volume’s theme of renunciation as in-progress. The speaker has not finished the revision process since the redactions are still present on the page, and there is more work to do. Thus, renouncing trauma is a continuous process that requires negation and reclaiming. Though the redactions themselves are visible, those blackened words remain private: the reader knows they once existed and what they were, but they no longer “matter” to the narrative. What does “matter” is the enduring text, and by extension, the rebirth that remains. This is what my students find most inspiring about The Renunciations.

I enjoy teaching courses that focus on the human experience, the tissue that connects all of us across time, space, and place. It holds the entirety of struggle and triumph, inclusion and exclusion, in a messy yet clean strand of inquiry that allows for a holistic interrogation of diverse existences. The challenge is getting students to connect with the abstract concepts that comprise human experience in concrete ways. Questions like, “When do we need to ‘give up’ in order to grow?” might seem intimidating, but Kelly addresses such queries in The Renunciations quite tangibly. Students are able to connect with her writing on a personal level. The “giving up” that she narrates is an ongoing process, but what remains after the metaphorical redactions is the speaker’s moving refusal to be defined by her trauma.

Texts to Pair with The Renunciations:

Ralph Ellison, selections from Invisible Man (1952).

Gwendolyn Brooks, poems from In the Mecca (1968), including “In the Mecca,” “Boy Breaking Glass,” and “Malcolm X.”

Nell Dunn, Up the Junction (1963).

Ama Anima Nuamah, “You Are Woman,” “Bottom’s Up” (circa 2018).