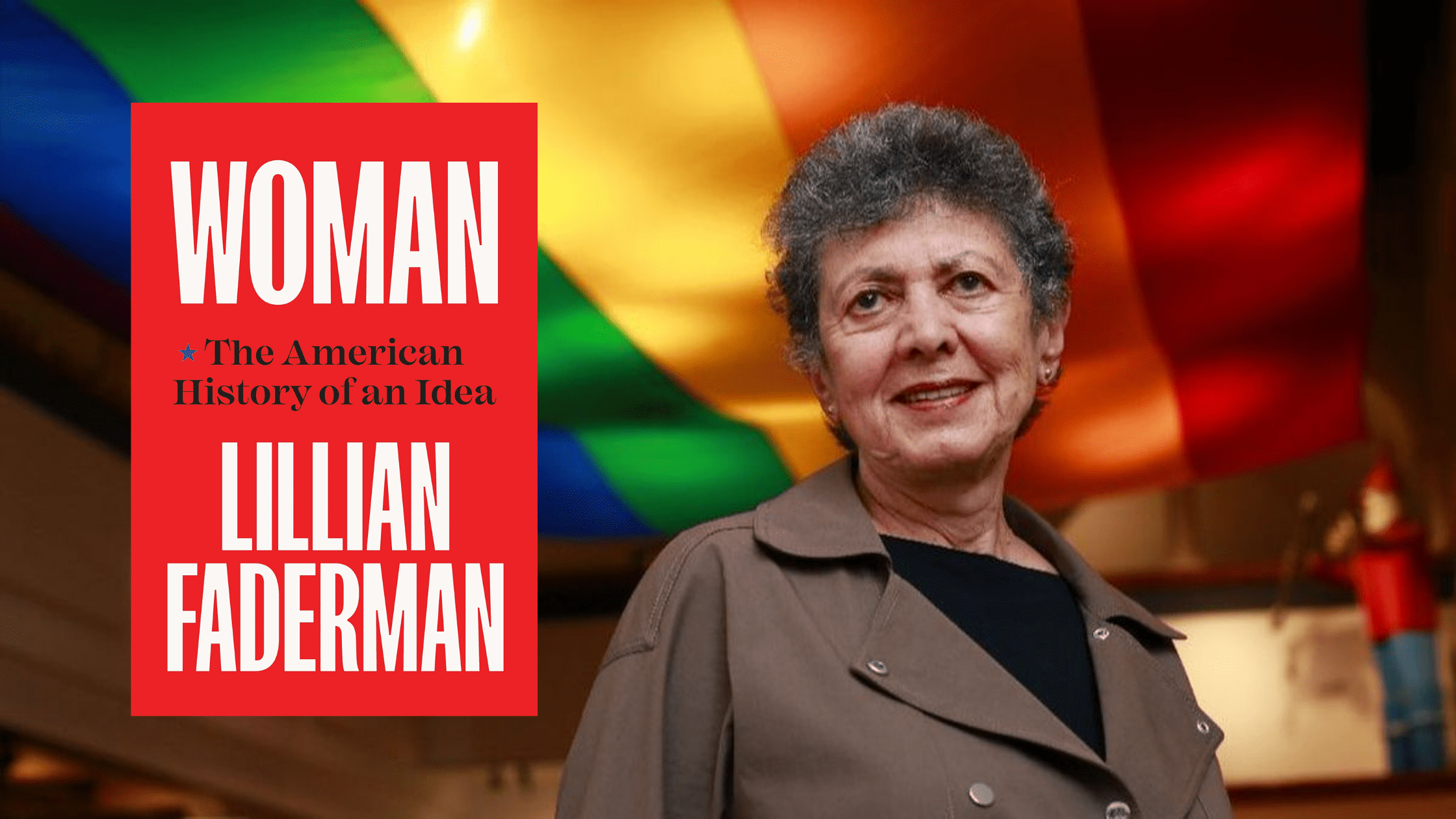

What connects American Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet across 400 years to rapper Cardi B? The answer, for Lillian Faderman, is the concept of womanhood, as she explores in her sharp, scrupulously-researched new book, “Woman: The American History of an Idea.”

Faderman, a professor emerita at California State University, Fresno, draws a line across 500 pages between the two icons. And she brings the same exhilarating vigor found in her 2015 book, “The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle.” It earned the Anisfield-Wolf nonfiction prize the following year.

“Woman” began in questions that Faderman’s adolescence posed to her. Born in 1940, the author recalls her junior high school classmates with their “short, tight skirts and see-through nylon blouses” in open rebellion against the mid-century television norms of women like Harriet Nelson and June Cleaver.

The most unruly ones ended up at the Ventura School for Girls, where they were sent to charm classes and church services meant to “reform the girls by inculcating in them the dominant culture’s ideal of womanhood.” This book wonders “how, when and why had that ideal of woman been created.”

Faderman wastes no time sharing who created the ideal: “For centuries, the men with the megaphones did not simply describe ‘woman,’ they prescribed who she must be. They left out of their prescription those who were beneath their concern.”

Faderman begins in the 17th century, exploring the Puritanical influences on white women in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the tyranny Black women faced on forced-labor estates in the Deep South, alongside the leadership some Indigenous women assumed in their nations. The scholar shifts her lens masterfully throughout the book, contrasting the experiences of privileged women with those disenfranchised. A standout is her chapter on women in higher education, full of nuggets such as the fact that Spelman College was named after Laura Spelman Rockefeller, Ohio abolitionist and wife of John D. Rockefeller.

Finalized over the course of the coronavirus pandemic, “Woman” touches on its still-unfolding effects on women’s economic agency. “The pandemic forced a recognition of how tenuous the expansion of women’s lives beyond the bounds of domesticity might be,” Faderman writes, noting the number of daycare centers that had shuttered. “Women can move out into the world only if they are childless or if their young children can be watched over.”

“Woman” closes with an examination of the ways womanhood has morphed within the last 20 years, touching on the expansion of gender identity among Gen Z and the ascent of Vice President Kamala Harris. There is no tidy conclusion.

Perhaps that’s the point, as Faderman writes in the epilogue: “It remains to be seen whether ‘woman’ will always be the default concept that takes hold in times of duress or whether ideas of ‘woman’ have now mutated so completely that there will never be a long return to the prison of gender.”

Readers rooting for the latter would do well to take up this book.