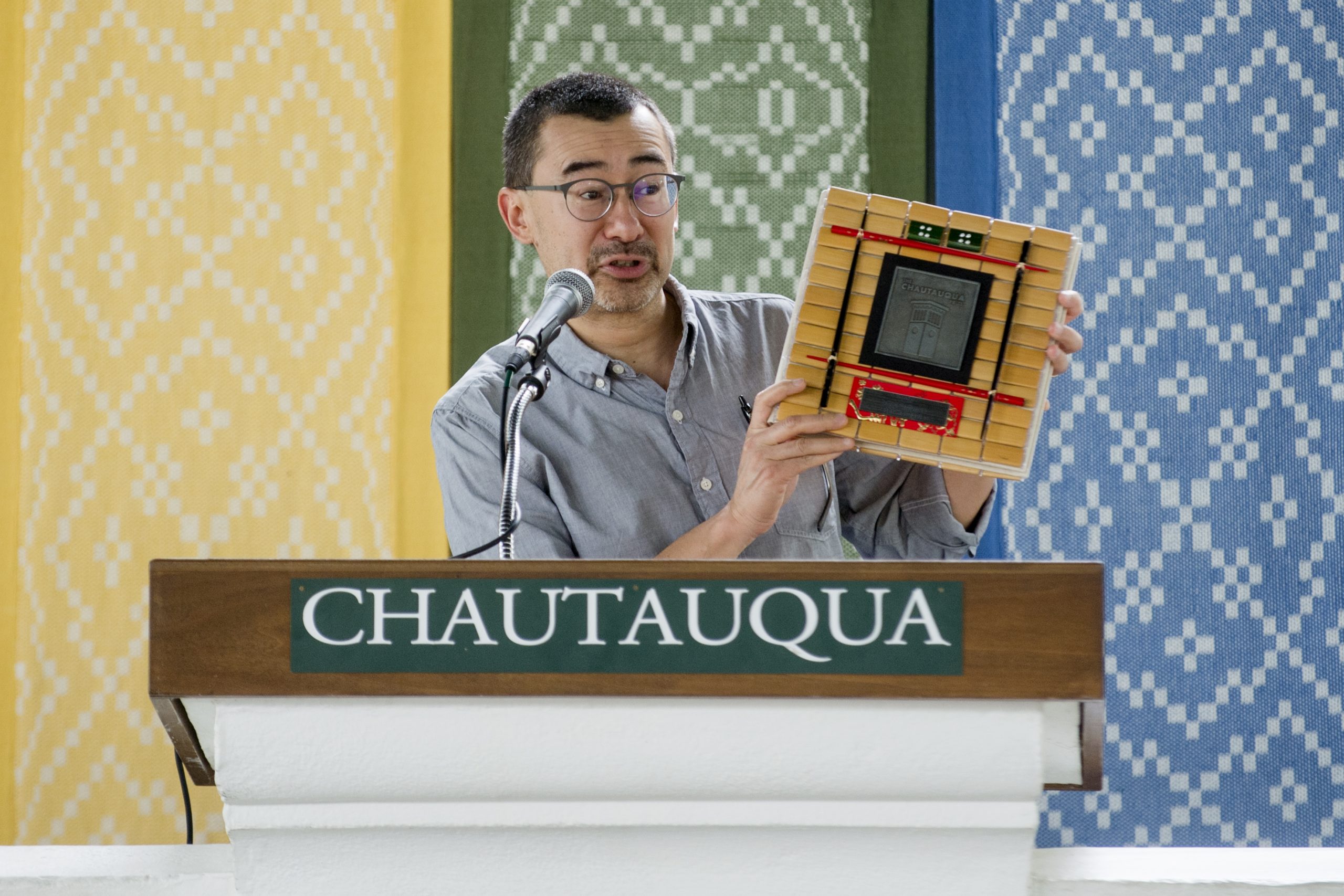

Peter Ho Davies – a gracious, wise and observant British-born fiction writer – welcomed a question about the title of his most recent work, “The Fortunes.” It won both the Chautauqua Prize and an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award this year.

Tentatively called “Tell it Slant,” a reference both to Emily Dickenson and a racial slur against Asians, the edgy title pleased both Davies and his editor. But it gave a large book chain pause. And Davies realized its tone fit just one of the four chapters – short stories in a way – that compose his novel.

Davies, clearly attuned to nuance, told an appreciative crowd at the Chautauqua Institute that he understood the booksellers’ reservations. But he is also intrigued by the phenomena of groups reclaiming labels originally meant to denigrate – “queer” in the LGBTQ vernacular, “suffragette” among feminists and sometimes the N-word among African Americans.

And the June U.S. Supreme Court decision greenlighting the use of “The Slants” as the trademark name for an Asian-American band fits into this language-subverting vein, noted the University of Michigan professor.

“The Fortunes,” Davies said, is a good titular fit: “It captures the Chinese interest in luck and it touches on questions of fate. It is plural, which reflects multiple characters, and it gestures at that most Chinese-American of tokens, the fortune cookie.”

Davies, 50, spent a week at Lake Chautauqua with his wife, novelist Lynne Raughley, and son Owen, to celebrate “The Fortunes” as the sixth winner of The Chautauqua Prize. It recognizes a book annually that contributes to literature and is a pleasure to read.

In four linked sections, “The Fortunes” considers a valet in the 1860s California Gold Rush, the actress Anna May Wong during the 1930s, the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin by a disgruntled Detroit autoworker, and the adoption of a Chinese daughter by contemporary American parents. Each protagonist is a fictional version of a historical figure, including the half-Chinese adoptive father, who has a cluster of characteristics in common with Davies himself.

“The book is an immigrant narrative caught up in an obsession of mine: identity,” said the author, whose dentist mother was Malaysian Chinese and father was a Welsh engineer.

“How do we find ways to get beneath the skin of history to tell someone’s story?” he asked. “I was lucky to come across a reference to a Chinese manservant to Charles Crocker, a baron of the Central Pacific Railroad often credited with bringing in Chinese to build the railroads. His servant, a valet I imagine, is Ah Ling, someone I think of as Asian Zero. And Ling becomes the first example of that problematic category: the model minority.”

Ah Ling came to stand for the burden of racial representation, Davies said, which led him to the famously beautiful actress Anna May Wong. The song “These Foolish Things” was written for her by one of her lovers.

“She’s famous for being Chinese but she is limited in the roles she can depict because she can’t kiss on screen. It is against the anti-miscegenation laws,” Davies explained. And once a white man was cast as the lead in film version of Pearl Buck’s “The Good Earth,” it meant Anna May Wong could not play the role many considered her destiny: O-lan.

The third section of “The Fortunes” ponders the beating death of Vincent Chin, adopted from Hong Kong and mistaken for Japanese by a drunk Detroit autoworker angry over the 1982 economic downturn. Chin, 27, was buried on what was to have been his wedding day.

“We’ve all done this. I’ve done this. It can have comedic implications,” Davies said of mistaken identity among Asians. A reader once approached Davies to inquire if he was the Japanese novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, who in turn was once asked if he was Jackie Chan.

In the final story, the act of adoption brings identify formation to the fore. “The book is hybrid in its form and is about people who are hybrid in their identities,” Davies said. Although he didn’t start intending it, form serves content.

Because everyone has multiple identities, people — especially of mixed race — must wrestle with authenticity: “Who am I? How do others seem me?”

Humor, a Davies trademark, helps a reader navigate weighty topics such as race. The interplay, he believes, lets in some light.