The Cleveland Foundation today unveiled the winners of its 83rd Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Marlon James, a 2015 Anisfield-Wolf honoree, made the announcement. The 2018 recipients of the only national juried prize for literature that confronts racism and examines diversity are:

- Shane McCrae, In the Language of My Captor, Poetry

- N. Scott Momaday, Lifetime Achievement

- Jesmyn Ward, Sing, Unburied, Sing, Fiction

- Kevin Young, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News, Nonfiction

“The new Anisfield-Wolf winners deepen our insights on race and diversity,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., who chairs

the jury. “This year, we honor a lyrical novel haunted by a Mississippi prison farm, a book of exceptional poetry on

what freedom means in captivity, and a breakthrough history of the hoax that speaks to this political moment. All is

capped by the lifetime achievement of N. Scott Momaday, the dean of Native American letters.”

We invite you to join us September 27 as we honor these winners at the State Theatre in Cleveland, in a ceremony emceed by Jury Chair Gates. The ceremony will be part of the third annual Cleveland Book Week, slated for September 24-29. Join our mailing list to be the first to know when the free tickets are available.

Shane McCrae

Shane McCrae interrogates history and perspective with his fifth book, In the Language of My Captor, including

the connections between racism and love. He uses historical persona poems and prose memoir to address the

illusory freedom of both black and white Americans. “These voices worm their way inside your head; deceptively

simple language layers complexity upon complexity until we are shared in the same socialized racial webbing as

the African exhibited at the zoo or the Jim Crow universe that Banjo Yes learned to survive in (‘You can be free//Or

you can live’),” says Anisfield-Wolf Juror Rita Dove. Raised in Texas and California, McCrae taught at Oberlin College for three years before joining the faculty of Columbia University last year. He lives in Manhattan with his

family.

N. Scott Momaday

N. Scott Momaday remade American literature in 1966 with his first novel, House Made of Dawn. It tells the story

of a modern soldier trying to resume his life in Indian Country. The slim book won a Pulitzer Prize, but Momaday

prefers writing poetry, the form his work most often takes. Anisfield-Wolf Jury Chair Gates says Momaday “is at

root a storyteller who both preserves and expands Native American culture in his critically praised, transformative

writing.” He is also a watercolorist, playwright, scholar, professor and essayist. Momaday was born a Kiowa in

Oklahoma and grew up in the Indian southwest. He earned a doctorate at Stanford University, joined its faculty,

and taught American literature widely, including in Moscow. In 2007, President George W. Bush awarded

Momaday a National Medal of Arts. He lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Jesmyn Ward

Jesmyn Ward is the only woman in American letters to receive two National Book Awards, one for her first novel,

Salvage the Bones, and another last year for Sing, Unburied, Sing. Both are set in fictional Bois Sauvage, a place

rooted in the rural Gulf Coast of Mississippi. Critics have compared Bois Sauvage to William Faulkner’s fictional

Yoknapatawpha County and Ward’s prose to Toni Morrison’s. Sing, Unburied, Sing serves as a road book, a ghost

story and a tale of sibling love. Anisfield-Wolf juror Joyce Carol Oates called it “a beautifully rendered,

heartbreaking, savage and tender novel.” Ward, who won a MacArthur “genius grant” last fall, lives with her family

in Pas Christian, Miss. She is a professor at Tulane University.

Kevin Young

Kevin Young is a public intellectual, the editor of eight books and the author of 13, including Bunk: The Rise of

Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News. He spent six years researching and writing

this cultural history of the covert American love of the con, and its entanglement with racial history. After 12 years

teaching at Emory University, Young became the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,

and the poetry editor for The New Yorker. Anisfield-Wolf Juror Steven Pinker calls Bunk “rich, informative,

interesting, original and above all timely,” and Juror Joyce Carol Oates says “it should be required reading in all

U.S. schools.”

Matthew Desmond thinks America can’t see itself clearly.

“We’re the richest democracy with the worst poverty. There’s not another advanced society that has the kind of poverty we have,” the sociologist said as he paced the stage at the State Theater in Cleveland’s Playhouse Square.

Dressed casually in a black pullover, Desmond’s talk was the marquee event for One Community Reads, the three-month book club for Greater Cleveland residents to rally around “Evicted,” his Pulitzer prize-winning book on poverty and housing inequality. It is focused on two neighborhoods in Milwaukee and is subtitled “Poverty and Profit in the American City.”

More than 2,000 came out to hear the Princeton University professor. Desmond spent more than a year embedded in Milwaukee’s poorest neighborhoods, charting the challenges of eight families and their landlords.

The statistics for Milwaukee are dire — nearly 1 in 8 renters have experienced at least one eviction. In Cuyahoga County in 2016, some 27,000 families were officially evicted, reported Judge Ronald J.H. O’Leary of Cleveland Municipal Housing Court. That year, one in five renting families in Euclid were forced out of their homes, he said February 23 at the City Club of Cleveland.

Once evictions were rare enough to gather crowds and protests, Desmond writes. But in the last decade, the number has skyrocketed. As an ethnographer, Desmond wanted to know why.

The professor, 38, became a MacArthur Foundation fellow in 2015, the same class of “genius” grant winners that honored playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda and writer Ta-Nehisi Coates. His soft speaking voice contains a hint of Southern twang, despite his upbringing in Winslow, Arizona, the son of a preacher and his wife.

As a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he began laying the groundwork for “Evicted.” While in Milwaukee, Desmond followed landlords as they collected rent and handed out eviction notices; he accompanied renters everywhere — to church and AA meetings, shelters and funerals.

He also accompanied them to housing court, where he quickly noticed a stark pattern: single black mothers, often returning again and again, stuck in a cycle of poverty and unstable housing. Drawing a parallel to the crisis of mass incarceration, Desmond noted in Cleveland: “Poor black men were locked up. Poor black women were locked out.”

Eviction pushes families deeper into disadvantage, he argues, adding that eviction is a cause of poverty as much as it is a consequence. The stress of losing a roof over your head — and the logistics of replacing possessions, routines and stability — can hurt job performance and mental health.

“With unstable shelter, everything else falls apart,” Desmond said. “How do we deliver on that obligation?” He wants the federal housing program expanded to include all households below the federal poverty line. Currently, 74 percent of poor families receive no housing assistance, forcing them into grim decisions between paying rent and buying practically anything else. Poor families who achieve stable housing shift their dollars most urgently into food.

Ideally, Desmond said, poor households should spend no more than 30 percent of their income on housing. Some now pay as much as 70 to 80 percent, heightening their risk for eviction.

To pay such a federal expansion, Desmond suggests capping the mortgage tax deductions for the wealthy, who account for about 6 percent of homeowners. “That would fundamentally change the face of poverty in America,” he said. “It would drive down family homelessness. It would make eviction rare again.”

Continuing the discussion on poverty and housing inequality, young student artists from Twelve Literary Arts will host a staged reading of “Evicted” at the East Cleveland Public Library on Wednesday, April 4, at 10 a.m. It’s free and open to the public.

The thrill of writing as clear as water ran through this year’s National Book Critics Circle awards, bookended by the valedictory appearance of nonfiction master John McPhee and the bracing arrival of poet Layli Long Soldier.

McPhee, who has sharpened the reading lives of generations and taught hundreds of journalists at Princeton University, was gracious and brief in accepting the Ivan Sandrof Award for Lifetime Achievement at the New School in Manhattan. He paid homage to former New Yorker editor Wallace Shawn, whose careful edit of McPhee’s first piece in 1963 was marked by Shawn’s deliberate words: “It takes as long as it takes.”

“A lifetime of writing. How did that happen?” asked McPhee, 87, as he accepted the prize. National Public Radio host Stacey Vanek Smith praised her mentor’s prose as “writing in the absence of intruding artifice.” She said she had thought at least 1,000 times of certain passages in “Coming into the Country,” McPhee’s classic work about the Alaskan backcountry.

Layli Long Soldier won in poetry for “Whereas,” mesmerizing the audience at the New School in Manhattan with a reading of a poem in which a grown daughter mistakes her father’s cry for a sneeze – having never heard him cry. She is a member of the Oglala Lakota nation and lives in Santa Fe.

Another first-time author, Carina Chocano, won in criticism for her 21 essays called “You Play the Girl: On Playboy Bunnies, Stepford Wives, Train Wrecks and Other Mixed Messages.”

The funny, incisive Los Angeles writer said she formed the idea for this book in 2008 when, as a movie critic, she was imbibing a steady diet of pop images of women in film. “Still, I was afraid to write this book, a woman speaking against the official line.”

NBCC board member Walton Muyumba observed, “We seem to tell ourselves movie and TV stories, Chocano suggests, in order to perpetuate old lies about gender, generally, and women, specifically. In fact, we seem to find deep pleasure in their continuous repetition. . . Chocano doesn’t send the readers down the rabbit hole (we’re living in Wonderland already) so much as she uses these pieces like smelling salts to awaken us to our collective gas-lighting.”

Biography honored another kind of cultural exemplar: Laura Ingalls Wilder, captured in the marvelous book “Prairie Fires” by Caroline Fraser. Wilder transformed her family’s struggle with poverty, disappointment and loss into fiction that has never gone out of print, has been translated into 45 languages, and sold more than 60 million books, Fraser said. The “Little House” titles cemented American pioneer mythology with a darkly libertarian streak.

“Laura Ingalls Wilder endures,” notes NBCC board member Elizabeth Taylor, ”and now future generations can read Fraser’s marvelous biography and understand her vision of how Ingalls dreams of the frontier. Caroline Fraser has brilliantly recast our understanding of Laura Ingalls Wilders’ life and times, and affirmed her influence in shaping the myth of the iconic West.”

A dissemination of a different set of ideas is characterized in Frances FitzGerald’s “The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America.” It won in nonfiction. FitzGerald quoted Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s admonition as a potent form of prosperity theology: “If you pray for a camper, tell Him what color; you don’t make God do your shopping.”

Taylor writes, “In convincing detail, FitzGerald charts the evolution of evangelism from a religious to a political movement.” The author thanked Jerry Falwell and his church in Lynchburg, Va., for their welcome and patience with her journalism.

In autobiography, the London-based filmmaker Xiaolu Gau won for “Nine Continents: A Memoir In and Out of China.” Critic Marion Winik describes it as “a thrilling, fist-pumping kind of story” about the author’s escape from cruelty and poverty in Communist China, salted with “a funny and entertaining disquisition” on why it is so hard for Chinese people to learn the English language.

Two Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards writers were among the 30 finalists: Edwidge Danticat for her exquisite book about mortality and her mother’s cancer, “The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story;” and Mohsin Hamid for his evocative and genre-bending novel “Exit West.”

Joan Silber won the fiction prize for “Improvement,” her seventh novel. It follows a single mother in New York, her four-year-old son, her free-spirited aunt and a boyfriend with plans to smuggle cigarettes across state lines. “There is not a wasted word in the novel’s 227 pages, which nevertheless contain multitudes,” writes NBCC board member Tom Beer.

“I’m always happy when someone describes my fiction as generous,” Silber said as she accepted the prize. “If nothing else, fiction reminds us that others have interior lives.”

For the first time in NBCC history, the winners across all six book categories were women.

Can the United States transition “from being an occupier to being a neighbor”?

So asks gkisedtanamoogk, a Native man living in Maine. He poses this question in “Dawnland,” a moving 90-minute documentary that the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards is proud to sponsor this year at the Cleveland International Film Festival.

The documentary follows four key participants in a truth and reconciliation commission entered into five years ago by the Wabanaki people and the state of Maine. It centers on the consequences of decades of government policy that ripped Native children from their families and placed them in foster homes.

The commission, which ran for 27 months, reported that between 2002 and 2013, Native children in Maine were five times more likely to be forced from their homes than non-Native children.

“Our film,” says Bruce Duthu, a Dartmouth professor of Native studies, “reveals a practice of state power that is ongoing, state action directed at the heart of the family and depriving individuals of something that I think most of us take for granted: the idea not only that we can have children but raise them the way that we want to.”

Duthu looks into the camera to say, “When state power deprives people of that right, we should all be concerned.”

The documentary will screen at Tower City Cinemas on three dates: 8:30 p.m. Friday, April 13; 1:20 p.m. Saturday, April 14 with a film forum and 9:20 a.m. Sunday, April 15. You will receive a $2 discount per ticket using the Anisfield-Wolf code: ANW0. Tickets go on sale March 23.

“It is hard to fathom for many in Maine that genocide occurred here,” the commission report states, “much less that it continues to occur in a cultural form.”

Jill Lepore is restless.

The Harvard historian prefers to walk while she thinks, and stand when she talks. And so she stood before perhaps 800 guests gathered in Cleveland to hear her ponder whether a divided nation can own a shared past.

“A nation born in contradiction, liberty in a land of slavery, will fight forever over the meaning of its history,” she writes in These Truths: A History of the United States, a 1,000-page civics lesson that W.W. Norton will publish in September.

Sweeping American histories were once common, particularly in the 1930s, Lepore said. They mustered an argument for American democracy, a rebuttal in the teeth of Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and their ilk. Now the nation is divided down the middle, she observed, with the hero of one half – Barack Obama or Donald Trump – serving as the villain of the other.

Asked about economic inequality, Lepore acknowledged its rise since 1968. But it is race, not class, in her estimation, that undergirds our systems: “Race is the foundation of our politics in a way that is mainly horrifying,” she said. “I put race squarely at the center of the history of the United States – it really is the driver of our political change.”

With her third history, New York Burning, Lepore won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2006. It explores 18th-century, pre-Revolutionary War Manhattan, specifically the winter of 1741, when ten fires beset the seaport village. With each blaze, panicked whites saw more evidence of a slave uprising. In the end, 13 black men were burned at the stake, 17 hanged, and more than 100 black women and men were thrown into a dungeon beneath City Hall.

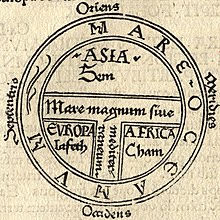

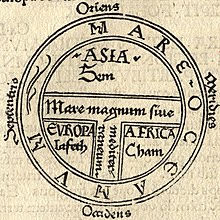

In her Cleveland presentation, Lepore, 51, started earlier still, noting that the very decision of where to begin a history is political. She flashed up an image on the multiple screens of the Maltz Performing Arts Center. Called the T-O Map (left), it dates to Medieval Spain and is considered the first conceptual map Westerners made of the world.

In her Cleveland presentation, Lepore, 51, started earlier still, noting that the very decision of where to begin a history is political. She flashed up an image on the multiple screens of the Maltz Performing Arts Center. Called the T-O Map (left), it dates to Medieval Spain and is considered the first conceptual map Westerners made of the world.

Next came the 1507 Waldseemuller map, made by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemuller. Its enormous popularity helped cement the name “America” for the new lands. “Like much of history, the naming was a crapshoot,” Lepore said.

She flashed up a painted portrait with a globe meant to cement Queen Elizabeth’s dominance over the new world (1588) as well as Powhatan’s Mantle (1607), meant to illustrate something similar about the regency of a Chesapeake chief.

The physical Constitution itself, widely printed and distributed in 1787, is a kind of map that argues “the people are sovereign by virtue of reading, a wholly new idea that sticks,” Lepore said. “The debate over the Constitution was really a strong one with Alexander Hamilton asking if people can rule themselves by coming up with a set of laws that govern by reason and choice instead of accident and force.”

One of the scholar’s favorite images portrays Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and feminist, knitting the nation – made in 1864, a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. The outline of the United States lies in yarn on her lap.

One of the scholar’s favorite images portrays Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and feminist, knitting the nation – made in 1864, a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. The outline of the United States lies in yarn on her lap.

Eight years earlier came a depiction that embraces the “technological sublime,” the idea that a technological fix could bind up the nation. In 1856 that was the transcontinental railroad. In 2000, it was an issue of Wired Magazine arguing that the internet would heal the nation’s political divisions in ten years.

As for the present, “historians make terrible prophets,” Lepore declared.

She noted that guns and abortion were apolitical topics a half-century ago. Now they serve as mirrored partisan gold-standards: Conservatives see guns as freedom and abortion as murder and liberals see guns as murder and abortion as freedom.

Lepore preferred, in writing the nation’s history, to dwell on a conversation between Henry Longfellow and his close friend Charles Sumner, during the perilous year 1848. The poet shared his new work, “The Building of the Ship of State,” in which the country is wrecked and sinks. Sumner implored Longfellow to give it a more optimistic cast. And when the poet did, it contained the famous lines: “Thou, too, sail on, O Ship of State!/Sail on, O Union, strong and great!”

Abraham Lincoln read these lines and wept. Sumner’s argument for optimism spoke deeply to Lepore. She deplores the fashionable radical pessimism – right or left – that characterizes our day, calling it “a kind of political cowardice.”

She cited a survey indicating that in the last year, only one in four Americans has had a political conversation with someone with whom they disagree – a perilous fact in itself.

Ever the historian, she suggested that citizens “wrestle with the facts, presume good will, use debate, examine the materials and make some arguments about the evidence.”

Leila Chatti, a poet who grew up in Michigan, will be the first Anisfield-Wolf Fellow in Writing and Editing, beginning her appointment this fall at the Cleveland State University Poetry Center. She has dual citizenship in Tunisia and the United States.

She was chosen from among almost 90 applicants.

“I am drawn to this fellowship in particular because I almost did not become a writer,” Chatti explained in her application. “As a child, I loved books, but because I had never encountered any written by or about people like me, I didn’t believe I would be able to write them; I thought writing was an occupation for other kinds of people, and that, by extension, my experience — my story — was not worth telling.

“It wasn’t until high school that I saw myself reflected on the page. An English teacher one day brought me a stack of books by Naomi Shihab Nye, and it was as if the world shifted. For the first time, I felt I, too, could do it — because I had seen it existed, I now knew it was possible.”

Chatti is currently living in Madison, Wis., where she is the Ron Wallace Poetry Fellow at the state university. Her poems are collected into two forthcoming chapbooks, Ebb and Tunsiya/Amrikiya, the 2017 Editors’ Selection from Bull City Press. Readers can find her work now in Ploughshares, Tin House, The Georgia Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, New England Review, Kenyon Review Online, Narrative, and The Rumpus.

The fellowship will have a community engagement piece that Chatti will design in Cleveland as she works on her first book.

“Once I was discouraged from writing early in my career for being too female and too Muslim, by those who were neither,” Chatti told the selection committee, “an instance of the systemic silencing in writing establishments and publishing that I hope to combat.”

Caryl Pagel, director of the CSU Poetry Center, called Chatti “a very gifted writer” and expressed her enthusiasm for the new position. “We hope to help address the longstanding lack of diversity in U.S. publishing, expand our literary service to the Cleveland community, and help raise our city’s profile as a center for innovative poetry and prose,” Pagel said.

Her sentiment was echoed by Karen R. Long, manager of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards: “The U.S. publishing industry is structured so that its members are 89 percent white, according to a 2014 industry-wide survey,” Long said. “We are delighted to address this inequity with something new under the sun: an editing and writing fellowship housed in the resurgent Cleveland State University Poetry Center. We see this as a new on-ramp that will benefit the literary arts, Cleveland and Leila Chatti herself.”

The fellowship runs two years and will bring the poet closer to her hometown. “I have a deep love for the Midwest, and a sense of responsibility to give back in any way I can,” Chatti said between sessions at the annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference. “I am so thrilled to return to my part of the country, the part that raised me.”

Here is her poem, “Fasting In Tunis”:

Longing, we say, because desire is full

of endless distances.

– ROBERT HASS

My God taught me hunger

is a gift, it sweetens

the meal. All day, I have gone without

because I know at the end I will

eat and be satisfied. In this way,

my desire is bearable.

I endure this day

as I have endured years of days

without the whole of your affection.

Your desire is one capable of rest.

Mine keeps its eyes open, stalks

through heat that quivers,

waits to be fed.

The sun burns a hole through

the sky and I am patient.

The ocean eats and eats

at the sand and still hungers.

I watch its wide blue tongue, knowing

you are on the other side.

What is greater: the distance between

these bodies, or their need?

Noon gapes, a vacant maw—

there is long to go

until the moon is served, white as a plate.

You are far and still sleeping;

the morning has not yet slunk into your bed,

its dreams so vast and solitary.

Once, long ago,

I touched you,

and I will touch you again—

your mouth a song

I remember, your mouth

a sugar I drink.

In her Cleveland presentation, Lepore, 51, started earlier still, noting that the very decision of where to begin a history is political. She flashed up an image on the multiple screens of the Maltz Performing Arts Center. Called the T-O Map (left), it dates to Medieval Spain and is considered the first conceptual map Westerners made of the world.

In her Cleveland presentation, Lepore, 51, started earlier still, noting that the very decision of where to begin a history is political. She flashed up an image on the multiple screens of the Maltz Performing Arts Center. Called the T-O Map (left), it dates to Medieval Spain and is considered the first conceptual map Westerners made of the world. One of the scholar’s favorite images portrays Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and feminist, knitting the nation – made in 1864, a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. The outline of the United States lies in yarn on her lap.

One of the scholar’s favorite images portrays Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and feminist, knitting the nation – made in 1864, a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. The outline of the United States lies in yarn on her lap.