Coretta Scott King begins her posthumous new memoir with a terrific metaphor: “Most people know me as Mrs. King. The wife of, the widow of, the mother of, the leader of. . .Makes me sound like the attachments that come with my vacuum cleaner.”

When she died in 2006 at age 78, 12,000 people came to her eight-hour Georgia funeral, including four U.S. presidents. In this sweeping memoir “My Life, My Love, My Legacy” King details her rise from a restricted childhood in Marion, Alabama, to become one of the most visible leaders of the Civil Rights movement. But as King plainly states, most people were still unable to separate her legacy from her husband’s, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

She writes that this never bothered her: “We did not have a his-and-hers mission. We were one soul, one goal, one love, one dream. The movement had become embedded in my DNA. It was not something I could choose — or refuse.”

As a young girl in the segregated south, she encountered injustice early. When she was 15, racists burned her family’s Alabama home to the ground on Thanksgiving. Huddled around the melted vinyl, her father instructed them to pray for the arsonists. This incident was “my first taste of evil, the kind that shows up at your door in such a way that you can never forget its smell, its taste, its sting.”

She moved north soon after, enrolling at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where she received her first taste of life outside of Jim Crow. Her studies then took her to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where she met Martin, a charismatic doctoral student who declared on their first date she would make a great wife.

They married in 1953 and had four children in succession — Yolanda, Martin III, Dexter and Bernice. King found it difficult to balance caring for young children and her music career while her husband was often orchestrating demonstrations, but she refused to be a stay-at-home mother. “I love being your wife and the mother of your children,” she shared with her husband one day, “but if that’s all I am to do, I’ll go crazy.”

Throughout the book, King bristles at being reduced to a background player. Her Freedom Concerts, well-attended international affairs in which she would use her classically trained voice to sing and tell stories about the movement, were one of the main fundraisers for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She notes that she was the one who first began collecting her husband’s speeches and notes, the first to intuit their value. She was brave and outspoken in ways her husband couldn’t be, she wrote, noting that she began speaking out against the Vietnam War years before he felt comfortable doing so.

But her presence in the movement wasn’t always well-received. One incident, in which she accompanied the men to the gate of the Kennedy White House in a limousine, only to have to hail a cab back to the hotel, particularly stung. Men at the top, including her husband, were often reluctant to give female leaders public credit. In this memoir, she praises organizers Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Juanita Abernathy and others for their ability to lead from the shadows.

For the most part, King’s memoir is beautifully written but cautious. She veers away from controversial topics such as her husband’s rumored extramarital affairs or the in-fighting between leaders. When she becomes introspective, on the verge of sorrow, she doesn’t linger there. Sadness and pity are luxuries she sets aside here, despite the horrors she endured.

King mentions just a few vacations with her husband during the height of the movement, always noting that they were “following doctor’s orders.” Toward the end of her life, she took a few trips with good friends Betty Shabazz, widow of Malcolm X, and Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of Medgar Evers. The trio offered each other a particular sisterhood. When they were together, their main goal was to “enjoy not being in charge of anything,” King wrote.

King closes the book with a call to action: “Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it with every generation.” This book may very well be the blueprint.

Sixty-six writers and artists – including seven Anisfield-Wolf recipients and two jury members – wrote an open letter to President Donald Trump asking him to desist from broadly banning travel to the United States by people from seven predominately Muslim countries. The letter, sponsored by PEN America, is timed to influence the president before he issues a second version of his original, sweeping travel ban, which is now stayed by the U.S. District Court of Appeals.

“Preventing international artists from contributing to American cultural life will not make America safer, and will damage its international prestige and influence,” wrote the signatories, who include poet Rita Dove and historian Simon Schama, panelists on the five-member Anisfield-Wolf jury.

The letter continues: “Arts and culture have the power to enable people to see beyond their differences. Creativity is an antidote to isolationism, paranoia, misunderstanding, and violent intolerance. In the countries most affected by the immigration ban, it is writers, artists, musicians, and filmmakers who are often at the vanguard in the fights against oppression and terror. Should it interrupt the ability of artists to travel, perform, and collaborate, such an Executive Order will aid those who would silence essential voices and exacerbate the hatreds that fuel global conflict.”

Anisfield-Wolf novelists who put their name to the letter include Chimamanda Adichie, Sandra Cisneros, Nicole Krauss, Chang-rae Lee and Zadie Smith. Nonfiction honorees include philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah and Andrew Solomon, president of PEN America.

“As writers and artists, we join PEN America in calling on you to rescind your Executive Order of January 27, 2017, and refrain from introducing any alternative measure that similarly impairs freedom of movement and the global exchange of arts and ideas,” they write.

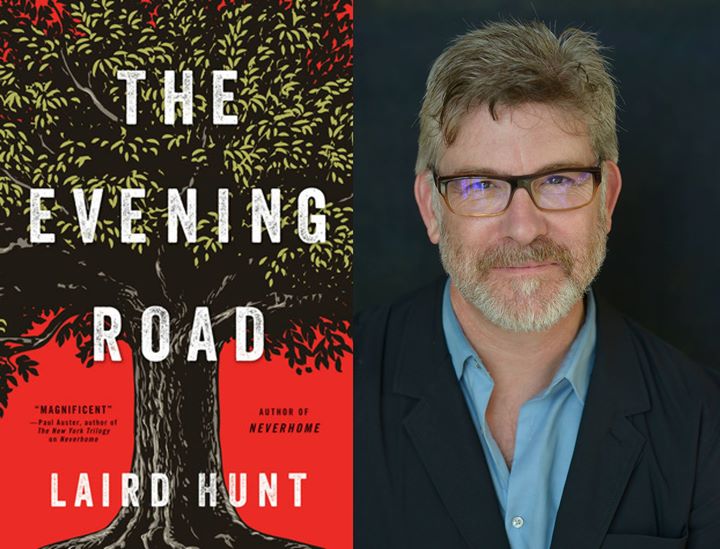

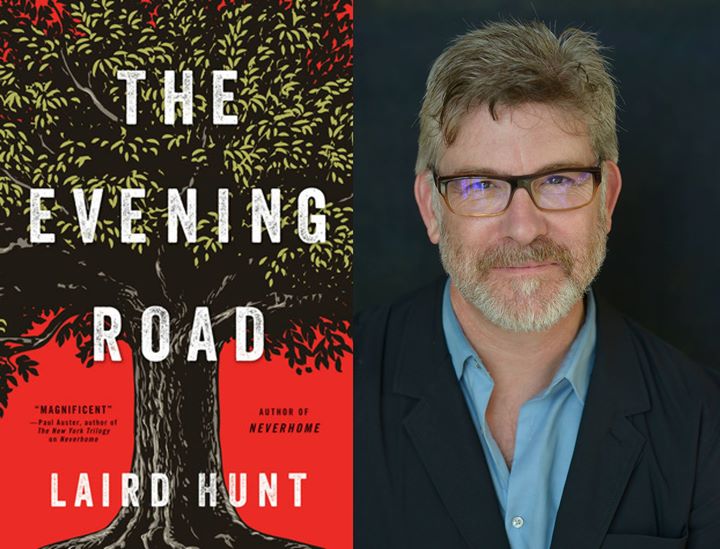

Laird Hunt, Wikipedia will tell you, “is an American writer, translator and academic.” True, as far as that goes. But readers of Hunt’s haunted, touched-by-the-fantastical fiction know it goes much deeper, and farther back.

At 48, Hunt’s beard has grayed, and he’s updated his stylish glasses since 2013, when he won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for his antebellum novel “Kind One.” Today he describes that work as the beginning of a triptych, which grew to include his mesmerizing Civil War story “Neverhome” and the newly minted “An Evening Road.” This third book unspools in 1930 over a single August day and night in a sweltering rural Indiana that became notorious for a double lynching.

Laird himself was a seventh-grade boy living in London who found himself abruptly transferred to his grandmother’s Indiana farm, about an hour from the spot where 40 years earlier the racist killings in small-town Marion were memorialized in souvenir postcards circulated around the world. Hunt said his family never spoke of these events within his earshot.

Indiana figures in all three novels in the triptych. “I am drawn to stories that are under-told, untold or under-represented in some way,” Hunt told a gathering at the Beachwood branch of the Cuyahoga County Public Library. “All the narrators of these novels are women – perhaps an audacious decision.”

And all these voices are informed by the inflection and character and humorous cast of his grandmother’s speech in her youth. “When she was angry or tired, her accent thickened and she dropped words,” Hunt said. No actual person spoke the way his characters do, “but they are meant to evoke what a 21st-century ear might expect from the past, not a slavish imitation.”

Bobbie Louise Hawkins, a short story writer who mentored Hunt, cautioned him against overdoing the vernacular. Indeed, one of the most dated aspects of “The Red Badge of Courage,” Hunt said, was Hart Crane’s thick hand with dialogue that wound up sounding as if he “stuck a big hayseed in his mouth.”

For “The Evening Road,” Hunt returned to Marion – which he calls Marvel in the novel – for extensive research. The jail from which the lynched men were dragged is still standing. “The jail looks like a medieval castle, with turrets and gargoyles,” he said. “In the ‘80s, it was turned into condos, if you can imagine.”

Hunt managed to enter a side door into the condominium building, now gone slightly to seed, to discover some of the jail’s original tilework and iron gating – “it is really haunting.”

Flannery O’Connor would feel at home here, and her fiction influences Hunt’s. “Strange things occur in all of our minds when we’re telling stories,” he said. In “Neverhome,” the narrator Ash Thompson suggests that she and an African-American woman might share the road for a spell, a preposterous notion in 1862 or 1863. Some sixty years later, the road is still preposterous for the two narrators of Hunt’s most recent novel – one anxious to get to the lynching, one anxious to flee.

Pigs loom in all three books, a creature young Laird smelled often in his rural adolescence. “They just keep appearing,” he mused. “Clearly, something has moved into my psyche. They stay present in my fiction—victimized, repulsed and yet desired.”

Hunt said his novel in progress, centered on witches in the 17th century, already contains a pair of pigs, unsettled and up on their hind legs.

Seven years ago, Hidden Figures author Margot Lee Shetterly discovered a great untold story in her own hometown.

Shetterly, 47, grew up in Hampton, Virginia surrounded by “extraordinary ordinary people,” men and women who toiled daily at NASA’s Langley Research Center, including her own father. But it wasn’t until a holiday visit when her husband asked a question—prompting her father’s story about the black women who calculated the trajectories of the first orbital space flight—that the gravitas really sunk in.

“These women’s lives intersected so many of the signature moments of what we call the American century,” Shetterly noted, “so why has it taken decades for us to tell their story?”

Flanked by colorful NASA backdrops and a full off-white astronaut’s suit, Shetterly shared her “aha moment” in front of a record-breaking crowd at Case Western Reserve University’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. convocation. Several schools bused in students. NASA employees milled around the lobby, passing out literature about other “hidden figures” and giving stickers to young people in attendance.

The four women at the center of Hidden Figures were NASA mathematicians who broke barriers—”intrepid women of science who also saw themselves as instruments of social change,” Shetterly said. “They exemplified your MLK theme this year of hope and solidarity.” Dorothy Vaughan was the first black supervisor in NASA history, heading up a team of “human computers.” Katherine Johnson worked with the Space Task Group, calculating the launch of astronaut John Glenn’s first orbit around the Earth, while Mary Jackson integrated the University of Virginia to become NASA’s first black aeronautical engineer. Christine Darden became one of the leading experts on sonic boom research.

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.”

As Shetterly dug into the research, the number of women who had worked at NASA began to rise exponentially. “A thousand women working as professional mathematicians, getting up and going to work at NASA, every day for decades,” she said. “Why didn’t we turn them into professional role models and use them to pull generations of young people, particularly young women, into science careers?”

Johnson, as a black woman born in 1918 in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, had just a two percent chance of finishing high school and a life expectancy of 35. Today, she is a lucid 98-year-old. “These women had excellent educations at HBCUs [Historically Black Colleges & Universities],” the author said, “and when the doors opened, they were as prepared as well as anyone.”

Shetterly, herself comfortable with calculations, landed in the financial sector after graduating from the University of Virginia, working at investment banks J.P Morgan and Merrill Lynch, before switching gears to publishing. In 2005, she moved to Mexico City with her husband Aran, where they spent 11 years publishing an independent magazine, Inside Mexico.

Shetterly sold the Hidden Figures book proposal to William Morrow in 2014, and received a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation to support the research. Almost immediately, Hollywood came calling. Within months, she was working as an historical consultant on the film adaptation before her book was even finished. It landed in theaters this winter and, to date, Shetterly has watched the movie six times and counting.

“I’m thrilled with how it translates to the screen,” she said, beaming. Academy voters agree with her — the adaptation has been nominated for three Oscars, including Best Picture.

So why did these black women remain in the shadows? Part of it was the classified nature of the work, Shetterly conceded. But the most egregious reason was the unrelenting segregation of the workplace itself, with separate offices, bathrooms and lunchrooms. The human computers wore skirts and heels every day, “their hedge against being mistaken for the cafeteria worker or the cleaning lady.”

Sexism also played its part. Computing was considered women’s work, Shetterly said, and defined as sub-professional. It often meant women solved the same problems and carried the same workload as their male counterparts, but were relegated to less pay, prestige and credit: “If today’s America gets a case of double vision when trying to focus its gaze on a black female mathematician or scientist, just think of the blind spot these women existed in sixty years ago.”

Of the four women Shetterly featured in the book, Johnson and Darden are still alive.

Last May, NASA honored Johnson’s three-decade career with a new 40,000-square-foot Langley research facility named for her. “I have always done my best,” she said at the ceremony. “At the time it was just another day’s work.”

The Evening Road returns Laird Hunt to Indiana, where the Anisfield-Wolf winner lived on his grandmother’s farm during his high school years, and where his feel for the rural Midwest and its uncelebrated people has few equals in American literature.

The Evening Road returns Laird Hunt to Indiana, where the Anisfield-Wolf winner lived on his grandmother’s farm during his high school years, and where his feel for the rural Midwest and its uncelebrated people has few equals in American literature.

This seventh novel springs from one of the nation’s most troubled wells. Hunt tells it over a single summer night, anchored in the bloody lynching of two men – Abram Smith and Thomas Shipp — in Marion, Indiana August 7, 1930.

“The events of that evening gave rise to the poem ‘Strange Fruit’ by Abel Meeropol, which was made famous as a song by Billie Holiday,” Hunt, now 48, writes about the source of his new novel. “At least 10,000 people (some put the number as high as 15k) flooded into the medium-sized town to attend the lynching, while the considerable African-American population of the town either stayed indoors or got out of town. While I don’t know if any of my family members attended the lynching that day/night, I found it strange and troubling that in all the years I lived with my grandmother on the farm, I never heard a whisper about what was an event of national significance and implication.”

Into that silence flowed The Evening Road, a haunting and disturbingly lyrical novel told in the voices of three women: a red-headed, big-chested secretary named Ottie Lee Henshaw trying to reach the lynching; Calla Destry, a light-skinned, intelligent and angry adolescent caught up in the mayhem, and, for the final 13 pages, the “touched” Sally Gunner, known for conversing with angels after she took a blow to her head.

Hunt is marvelous at characterization – Neverhome, his Civil War novel, rests on the mesmerizing authenticity of Ash Thompson, an Indiana farm woman who passes as a man to fight for the Union. And Kind One, his Anisfield-Wolf winner, gives readers two sisters who overthrow their 19th-century bondage on a remote Kentucky pig farm, then chain up and work the owner in return.

The Evening Road runs closer to home, chronologically, although Hunt is still liquid with his coordinates: an old crone recounts a version of Kind One almost as a spell while she is fixing Ottie Lee’s hair. Ottie Lee herself is a foul-mouthed, small town beauty with a lecherous boss and a quarrelsome husband. She falls in with three men trying to reach Marvel, as Hunt calls the town. She has wit and resourcefulness, as well as a cruelty that seems rooted in the grim past.

“The world can shut your mouth for you sometimes,” Ottie Lee reflects, having stumbled on a Quaker prayer vigil that mixed blacks and whites. “Get so big right there in front of you that it won’t fit in your eyes.” She also hears out a politician, firing up a picnic crowd he plans to lead to Marvel. He calls the lynchings “a torch of clarity to burn bright across the countryside during hard days. . . It is a difficult thing, a harsh thing, but it will burn things clear. Bring us back into balance. The hardest things always do.”

After 140 pages, Hunt leaves Ottie Lee. The second half of the book belongs to 16-year-old Calla, whose parents died in a laundry fire and who is boarding with a foster family in Marvel. She has stubbornly defied them to meet a beau, and winds up alone on the road trying to leave, but not before the crowd envelopes her: “Some were laughing like it was a true carnival, and others had on hard faces like they were marching to war. Some didn’t have on any expression at all, like they were killed folk had clawed themselves out of the cemetery just to walk into town and look glass-eyed up into the courthouse trees.”

Calla commits three brazen acts of defiance as she travels, and Hunt lets readers ponder how she and Ottie Lee run in parallel and diverge. Sudden blooms of violence pock the story, even as Hunt refrains from depicting the murders in Marvel. Instead, Calla wonders why whites “thought they needed to lift people up into the air to kill them. Their saints and sinners both. . . I hadn’t read the papers yet, hadn’t heard any accounts to turn the sky of my memories black and send me drifting forward through the dark. That would be during the days to come.”

The Evening Road may be a bucolic title, but its beckoning is urgent. Once more, Hunt draws up sorrow and dark light from the murderous past. The politician’s mother says “place like this glues itself to your bones; you don’t scrape it off.” Rather like Hunt’s masterful new novel itself.

Editor’s note: Laird Hunt will read from “The Evening Road” Monday, February 13 at the Beachwood branch of the Cuyahoga County Library. Join us.

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.”

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.” The Evening Road

The Evening Road