by Charles Ellenbogen

by Charles Ellenbogen

With all of the recent discussion about the changing faces on U.S. currency, some controversy emerged over a seemingly safe and definitely popular choice – Harriet Tubman. How many people, some asked, did she really lead to freedom? Do we really want the story of slavery memorialized on money? And, most persuasively, would Tubman herself have wanted this honor?

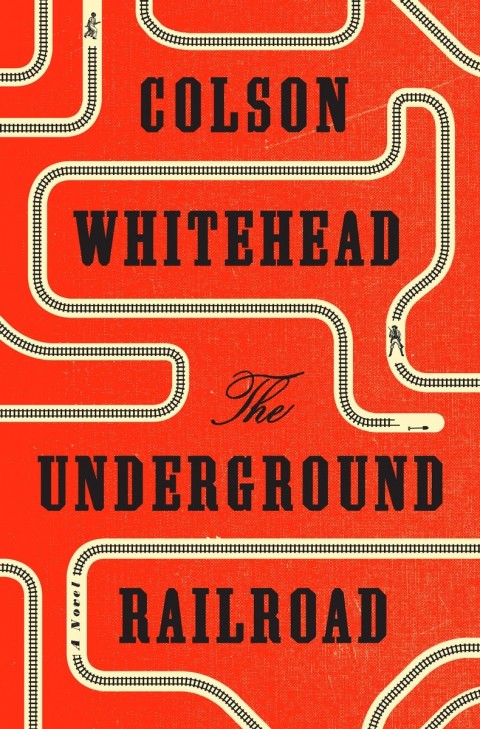

By not bringing up her name in his breathtakingly great new book, The Underground Railroad, Colson Whitehead, winner of the 2002 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for John Henry Days continues this conversation. Like most movements, the Railroad was made up of both the heroic conductors such as Tubman and the many nameless others who aided escaping slaves. Cora, Whitehead’s protagonist, and Caesar, who inspires Cora to run, make use of the Railroad on their escape.

But this is not Tubman’s railroad. Whitehead has, instead, imagined an actual train that runs underground. This is in keeping with Whitehead’s fictional moves elsewhere – he takes reality and winds it even more tightly to create a hybrid. This is not magical realism; this is Whitehead’s world. It is life intensified.

As with many journey stories, there are echoes of the Odyssey here. Indeed, Whitehead even has named a 10-year old former slave Homer. He drives a carriage for Ridgeway, a kind of Inspector Javert of slave hunters. Having failed to catch Cora’s mother, Mabel, Ridgeway is obsessed with capturing Cora, who is escaping from Georgia. Homer, having been freed, stays with Ridgeway; he has nowhere else to go. In fact, “Each night with meticulous care, Homer opened his satchel and removed a set of manacles. He locked himself to the driver’s seat, put the key in his pocket, and closed his eyes. Ridgeway caught Cora looking. ‘He says it’s the only way he can sleep.’” The soul aches. Absolutely.

While he does not shy away from the intricate details of suffering (you’ll want to look away, but you won’t), Whitehead’s language is both spartan and evocative. Near the novel’s beginning, Whitehead recounts the story of Ajarry, Cora’s grandmother being captured and sold. He explains that two “yellow-haired sailors rowed Ajarry out to the ship, humming. White skin like bone.” The language evokes the bones of the Middle Passage that Ajarry is about to take. We register the harshness – humming while taking someone to be sold – and the abruptness of the word ‘bone.’ The sailors, having lost their humanity, have become skeletons of human beings. When it comes to Whitehead’s writing, less is definitely more. Much more.

In the end, though, The Underground Railroad is not just Cora’s story. Or even the story of her family. It is a story about stories – the stories we tell each other, the stories we tell ourselves, the stories our documents give us, the stories we find in libraries and museums and on money, the stories that are forbidden to us, the stories of America. “Truth was a changing display in a shop window,” Whitehead writes, “manipulated by hands when you weren’t looking, alluring and ever out of reach.”

In Lies My Teacher Told Me, James Loewen offers a test of this premise. He suggests choosing one element in American history to track how it is treated in different sources over time. I chose John Brown. In some textbooks, he was absent or limited to a brief mention as a lunatic. In other texts, he earned several paragraphs and was depicted as a hero. “Cora blamed the people who wrote it down. People always got things wrong, on purpose as much as by accident,” Whitehead writes. This happens in textbooks. Novels too. Whitehead has gotten the Underground Railroad wrong, deliberately wrong, but to fault him is to miss the point. We must look, and we cannot look away. Whether we read, see an exhibit or watch a movie, we should do both and we should ask ourselves why we need to do both.

Whitehead is already racking up acclaim for this novel. Oprah chose it for her book club. The New York Times chose excerpts from it for its first broadsheet. There are, I am sure, more prizes in his future.

And I am happy for Whitehead’s success. It is time to move past considering him as a one or two-hit wonder — he wrote Zone One and Sag Harbor — and to start considering his work as a whole. If you haven’t read any of his work, The Underground Railroad is a great place to start. Some reviewers have noted how the novel resonates with today’s headlines. While this is true, such comments diminish the book. This novel will outlast headlines. It speaks to the truths underneath them. I read The Underground Railroad and was moved. Things I thought I knew shifted, sometimes slightly and sometimes violently. I was spectator, bystander, and, as hard as it is to admit it, participant. The novel is a journey, from captivity to freedom, from south to north, from past to present. It’s quite a ride.

Charles Ellenbogen teaches English at John F. Kennedy – Eagle Academy in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District.