About a year ago, I noticed a number of black women I follow online all wearing the same “Black Girls are Magic” t-shirt in their social media profiles. Launched by @ThePBG on Twitter, the t-shirt line was created in “celebration of the beauty, intelligence and power of Black women everywhere.”

It’s not hard to imagine those magical black women nestled somewhere reading journalist Tamara Winfrey Harris‘ first book, ‘The Sisters Are Alright: Changing the Broken Narrative of Black Women in America.” Her thesis is that black women are “neither innately damaged nor fundamentally flawed,” but instead are aching to be recognized for their full humanity.

So what is Winfrey Harris pushing back against? In a brisk 123 pages, the Indiana native investigates the “three-headed hydra” of black women stereotypes—the sassy Sapphire, the subservient Mammy and the hypersexual Jezebel— interspersing her own narrative with interviews from other black women. “Black women are not waiting to be fixed,” she writes. “They are fighting to be free — free to define themselves absent narratives driven by race and gender biases.” (Sound familiar?)

Winfrey Harris breaks these broad stereotypes into smaller, more nuanced discussions. She examines the sudden re-emergence of the natural hair movement and the back-breaking albatross that is the “strong black woman” syndrome. As one exasperated subject tells the author, “When are they going to realize I’m a complete phony? I just want to go back to bed. I don’t want to do this, because what if I’m not strong? What if I want to cry? What if I want to admit that things hurt? Who do I admit that to?”

I was most drawn to the chapter on parenting and the ways in which black women are chastised for their reproductive choices, from slavery to the present, despite the acknowledgement of the hurdles black women uniquely face. One anecdote was particularly haunting: a mother teaching her son to scream out his first and middle name if ever he was confronted by someone looking to harm him, a lesson she thought wise to impart after the confusion over who was screaming in the Trayvon Martin/George Zimmerman confrontation. This is “parenting while black” in the age of #BlackLivesMatter.

Harris’ work is not merely reactive. While she does push back on the negative stereotypes, her book is as much affirmation as it is repudiation. Nestled within each chapter are a few “Moments in Alright” vignettes, highlighting black women who created their own spaces and their own success stories.

There is something innately familiar about this work, starting with the old-school cover illustration of four happy black girls. As a black woman reading a text written by a black woman about being a black woman in America, it was the most invigorated I’ve felt in a long time.

And the timing couldn’t be better. When Ta-Nehisi Coates was asked about the lack of black women in his blockbuster Between the World and Me, published a week after Winfrey Harris’ book, he responded that the best answer was to “have more books” that can speak to all facets of the black community. Here’s hoping that some of those who rushed to buy Coates’ work find out The Sisters Are Alright too.

Anisfield-Wolf award winners are—almost by definition—civic minded.

They continue a generous tradition of adding extra public conversations each September in Cleveland. For those readers whose schedules don’t allow them to attend the awards ceremony or who want more than one chance to hear these gifted writers, here are the details:

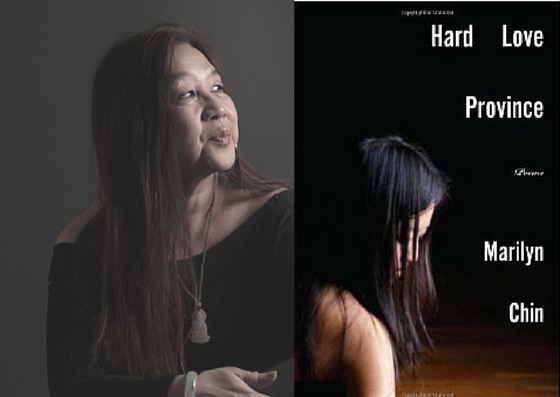

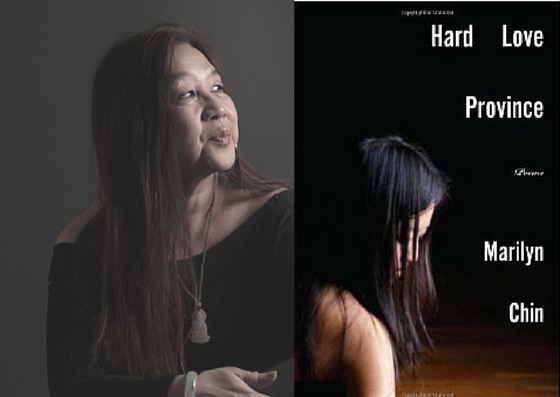

Poet Marilyn Chin, a professor at San Diego State University, will read and discuss her work in Hard Love Province. She will appear alongside John Carroll University’s Phil Metres, whose recent book, Sand Opera, has also drawn national honors. Both writers ponder identity, culture and Diaspora. They will appear at noon Wednesday, September 9 in the atrium of MOCA Cleveland, 11400 Euclid Ave.

Historian Richard S. Dunn will give a multi-media presentation on his landmark book, A Tale of Two Plantations: Slave Life and Labor in Jamaica and Virginia at 5 p.m. Wednesday September 9 at the Baker-Nord Center of Case Western Reserve University. Dunn spent more than four decades researching thousands of individuals over three generations, yielding ground-breaking insights into daily plantation life.

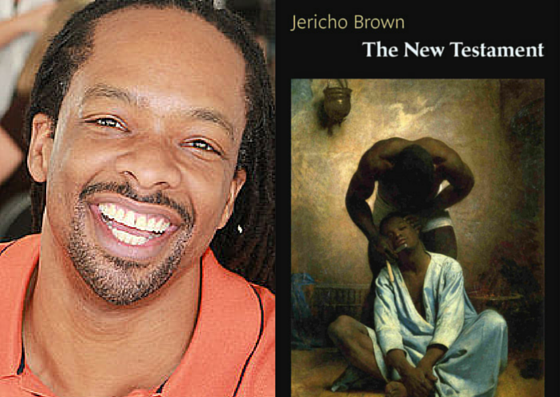

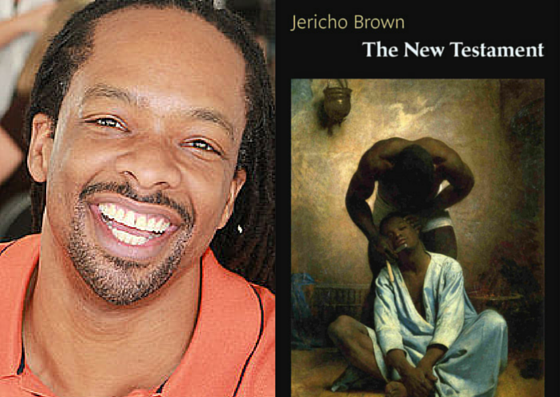

Poet Jericho Brown will read from his second book, The New Testament, at 7 p.m. Wednesday September 9 in the nave of Trinity Cathedral, 2230 Euclid Ave. in downtown Cleveland. This will be the first sacred setting for Brown’s musical poems. Brews and Prose is co-sponsoring this reading and the noon appearance of Chin and Metres.

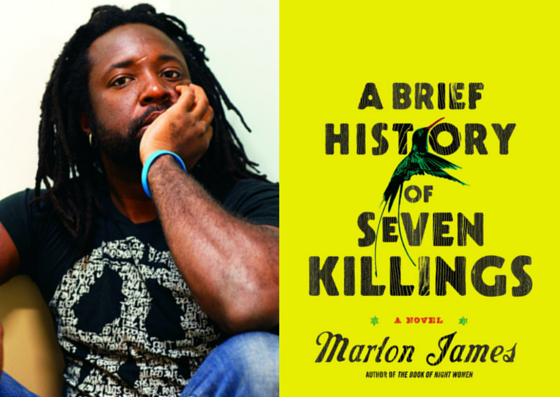

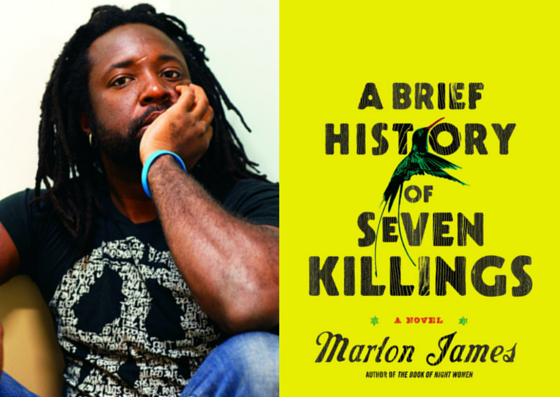

Novelist Marlon James will speak about his life and work at the City Club of Cleveland at noon Friday September 11. HBO optioned his Anisfield-Wolf winning book, A Brief History of Seven Killings, in April. James will take a sabbatical this upcoming academic year from teaching at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn., to write the screenplay.

The first three events are free. Registration is requested for the Dunn presentation. Those keen to hear Marlon James at the City Club should buy a lunch ticket or tune into the broadcast on WCPN 90.3 FM.

When a Missouri grand jury decided not to indict police officer Darren Wilson for killing 18-year-old Michael Brown, journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates watched his 15-year-old son Samori slowly stand up and walk into his own Baltimore bedroom to cry.

As Coates recounts this story in Between the World and Me, he writes that he followed his son, but did not hug or console him: “I did not tell you it would be okay, because I have never believed it would be okay. What I told you is what your grandparents tried to tell me: that this is your country, that this is your world, that this is your body, and you must find some way to live within all of it.”

Originally conceived as a collection of essays on the Civil War, Between the World and Me arrived four months ahead of its scheduled publication with a more urgent focus. Coates writes about the physical and psychological toll of being black in America, in the form of six letters/chapters to his son. Publisher Speigel and Grau bumped the release date up in response to the massacre of nine churchgoers in Charleston, as Between the World and Me “spoke to this moment.”

But the rush to get the book on shelves didn’t preclude Toni Morrison: “I’ve been wondering who might fill the intellectual void that plagued me after James Baldwin died,” Morrison had written. “Clearly it is Ta-Nehisi Coates.”

If Coates record-breaking 2014 reporting in “The Case for Reparations,” an Atlantic article, can be considered an intellectual appetizer, Between the World and Me serves as the entree.

Inspired by James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Coates has delivered a work that is as authoritative as it is inquisitive. Why can’t we, as a nation, come to terms with what we have wrought? Why do we constantly discuss “race” when we need to be eradicating racism? And perhaps most importantly, will we get it right anytime soon?

The Baltimore native connects his son’s disappointment in the Wilson non-indictment and the incident that hastened his own disillusionment with the American criminal justice system. In 2000, a Prince George’s County officer shot and killed Prince Jones, a Howard University student and friend of the author. This scorched Coates’ soul and psyche and he spends a sixth of his book writing about Jones.

He frames Jones’ slaying as an exemplar of what can befall the black body even in the best case scenario: a young man with a bright future, educated at some of the nation’s best schools, nurtured from birth toward greatness, bleeding to death outside his fiancee’s house in a case of mistaken identity. “Prince Jones was the superlative of all my fears,” Coates writes. “And if he, good Christian, scion of a striving class, patron saint of the twice as good could be forever bound, who then could not?”

Jones’ death is part of the reason Coates avoids shackling his son with “twice as good” generational mantra of black folks everywhere: “It struck me that perhaps the defining feature of being drafted into the black race was the inescapable robbery of time, because the moments we spent readying the mask or readying ourselves to accept half as much, could not be recovered….It is the raft of second chances for them and twenty-three-hour days for us.”

Not all in this book is grim. The most encouraging chapter centers on Coates’ undergraduate years at “The Mecca,” Howard University. Here he takes us on a virtual campus tour, leading up to the transformation many young adults undergo when they are learning on their own terms for the first time. He devours books three at a time and marvels that he’s walking in the footsteps of alumnae Lucille Clifton and Toni Morrison. Coates meets the woman he will marry, Kenyatta Matthews, a Chicagoan with a bit of wanderlust. (She inspired his first trip to Paris, where later this year, the couple and their son plan to relocate for a year.)

Read through my own lens as a black parent of black children, Between the World and Me is sobering. It offers no sense that the job will be made easier by magical conversations on how to navigate life safely in America. Coates’ parenting is blunt: “I have always believed that my job was not to hide the world from you but to guide you through it and this meant taking you into rooms where people would insult your intelligence, where thieves would try to enlist you in your own robbery and disguise their burning and looting as a celebration or a wake.”

One nitpick: In certain passages, Coates meanders around a subject as if figuratively speaking, he forgets his son is in the room. The message is still there, but the receiver is not so clear. Other reviewers have called into question whether Between the World and Me is too male-centric. Buzzfeed editor Shani O. Hilton writes that she was disappointed that the “black male experience is still used as a stand in for the black experience.”

Nevertheless, this book is a masterpiece, and here is a postscript: I would still like to read that Civil War book. What does one of the most fertile and curious minds of our era have to say about our nation’s deadliest war? He gives us a tease here, but let’s hope a full-bodied work is still on the way.

Between the World and Me goes on sale Tuesday, July 14.

“I’ll tell you what freedom is to me—no fear,” Nina Simone wistfully told an interviewer in 1968. “If I could have that half of my life…”

This search for freedom haunts each beat of “What Happened, Miss Simone,” the new Netflix-commissioned documentary on the award-winning singer, pianist and activist. The film, book-ended by Simone singing her classic “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free,” traces her journey from a piano prodigy in small town North Carolina to an international force of blues and soul.

“What Happened, Miss Simone” reaches viewers months before the highly controversial “Nina” biopic—in which Afro-Latina actress Zoe Saldana dons facial prosthetics to more closely resemble Simone. Simone’s only child, Broadway actress Lisa Simone Kelly, prefers the documentary: “[This film] reboots everything to what it’s supposed to be in terms of mom’s journey and mom’s life the way she deserves and the way she wants to be remembered in her own voice on her own terms.”

Born Eunice Waymon in 1933, the young girl’s early aptitude for music inspired a rare communal pride in her segregated town: both black and white residents contributed to a fund to send her to the Juilliard School in New York. When she applied to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, the admissions office turned her down. “It took me six months to realize it was because I was black,” Simone said. (The institute would later award her an honorary degree two days before her death in 2003.)

Fresh out of money, the 19-year-old took the first job she could find—playing piano in an Atlantic City bar: “The owner came in the second night and told me if I wanted to keep the job, I had to sing. Ninety dollars was more money than I ever heard of in my life, so I sang.”

She changed her name to Nina Simone to avoid having her preacher mother discover she was playing secular music for a living. Yet it was the classical training that made her stand out. Soon she found herself performing at jazz festivals, drawing attention with her booming vocals.

“What I was interested in was conveying an emotional message, which means using everything you’ve got inside you, sometimes to barely make a note, or if you have to strain to sing, you sing,” she explained. “So sometimes I sound like gravel and sometimes I sound like coffee and cream.”

Her then-husband Andrew Stroud quit his job as a New York City police sergeant to oversee her career. Mutual friends described him as a man who could spook you with one word; their love affair quickly turned violent.

“Andrew protected me against everybody but himself,” she spat in one interview. “He wrapped himself around me like a snake.”

While Simone aspired to commercial success, the relentless pressure of being the breadwinner for an entire entourage— at one point she counted 19 people on her payroll—exhausted her: “Inside I’m screaming, ‘Someone help me’ but the sound isn’t audible – like screaming without a voice,” she wrote in her journal. “Nobody’s going to understand or care that I’m too tired. I’m very aware of that,” she later said.

Stroud recounted a story of Simone having a mental breakdown before a performance. “She had a can of shoe polish. She was putting it in her hair. She began talking gibberish and she was totally out of it, incoherent.” No one took her to get help; instead, Stroud took her arm and escorted her to the piano on stage. The show must go on.

Kelly, who also produced the film, uses her screen time to “explain” her mother, to smooth some of the controversial aspects of the entertainer’s life. For the most part, she is successful: “She was happiest doing music. I think that was her salvation. It was the one thing she didn’t have to think about.”

As her marriage imploded, Simone entered the burgeoning civil rights movement, flourishing in the company of contemporaries like James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry and Langston Hughes. “I could let myself be heard about what I’d been feeling all the time.” The 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four little girls enraged her. She wrote “Mississippi Goddam,” which soon became her best-known song and an anthem of the movement.

As Simone’s priorities shifted to what she called “civil rights music,” promoters shifted away and her career stalled. After stints in Barbados and Liberia, she settled in Europe to mount a comeback. Friends took in her disheveled appearance and odd behavior and took her to the doctor, where she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a disease many suspected she struggled with most of her life.

It’s never quite clear how close Simone would have considered some of the individuals tapped to interview; director Liz Gruber’s decision to gloss over their connection weakens the film. But the inclusion of Simone’s journal entries—she talks about contemplating suicide, of taking pills simply to function—gives an unvarnished insight into a woman of genius whose complexity makes her difficult to sum up, or pin down.