The Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards will expand its reach in 2015 with the addition of a second scholar at Case Western Reserve University teaching about racism and the awards literature, starting in the fall. The Cleveland University posted a description of the fellowship this month.

The individual who is hired will join Dr. Lisa Nielson, a pioneering partner to the book awards. She has been instrumental in bringing Anisfield-Wolf literature into the university canon. A classically-trained musician and scholar, Nielson has won major grants and two university teaching awards since she became the first Anisfield-Wolf SAGES scholar in the fall of 2011.

Her success has bred much success: students who take multiple courses from her, and who have completed original research on some of the writers awarded the prize in the past 80 years. Nielson holds a “bad movie night” for students and ad hoc discussion sessions on Friday afternoons.

In 2014, Nielson wrote a moving essay about her work in the classroom during the last three years, admitting that teaching about racism keeps her up at night:

Listening to my students, I find a generation that thinks creatively about politics, gender, race, sexualities. They consume music and media differently than I do and express themselves in new ways. Their desire for inclusion and capacity for acceptance astonishes me; they inspire me to think more fluidly about myself. They have changed me profoundly as a teacher and as a human being.

Edith Anisfield Wolf created the book awards to recognize literature dedicated to fostering conversations about tolerance and cultural acceptance. Through these books and my students, I am constantly working to hear what I think was her real message: Listen.

“I am not a person preoccupied by race,” said the groundbreaking journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault, instantly believable even in the paradox that her place in history is inextricably tied to race.

Exuding warmth and wit and height – even in low-heeled boots – Hunter-Gault asked about 200 listeners at Case Western Reserve University, “What would Dr. King be dreaming now – in the deep South and in the up South?”

When she was Charlayne Hunter, oldest child of a Methodist army chaplain and his wife, the teenager spotted King on the sidewalk in Atlanta outside his father’s church, Ebenezer Baptist. “I saw Dr. King on the street and I went to him and he said, ‘I know who you are. And I am so proud of you and Hamilton Holmes.’”

The minister embraced the willowy 19-year-old, who was withstanding systemic and very personal hatred leveled at her and Holmes as the first two African-Americans enrolled in the University of Georgia. When the duo arrived in January 1961, a mob taunted them and hurled bricks and bottles to punctuate chants of “Kill ‘em.” The angry segregationists wound up smashing windows in Hunter’s dormitory and a panicked administration expelled the black students “for their own safety.” After the courts reinstated them, Holmes graduated to become an orthopedic surgeon and Hunter went on to a celebrated career in journalism at the New Yorker, the New York Times, NPR and CNN.

Wearing a dramatic shawl that matched impeccable lavender nails, Hunter-Gault at age 72 confided that her childhood ambition ignited as she read the Brenda Starr comic strip, sitting alongside her grandmother in Covington, Ga. Both she and Holmes attended Atlanta’s prestigious black high school, Henry McNeal Turner, where young Hamilton was valedictorian and young Charlayne graduated third in their class.

As her Cleveland listeners warmed to her remarks, Hunter-Gault beamed: “We can do some church here.” Textbooks, she remembered, were missing pages and outdated, passed along from the white schools. Her Atlanta teachers “couldn’t give us a first-class education, but they labored to give us a first-class sense of ourselves.”

When she and Holmes did reach the University of Georgia under historic court order, they were met with a daily barrage of the N-word. Hunter-Gault remembered looking around, unable to believe the hatred was meant for her, a queen in her own mind: “I was wrapped in the armor of the black family. My grandfather was a preacher but my grandmother was a saint.” Under these trying circumstances, Hunter-Gault said, it was easy for her to pray.

And when King praised her on that sidewalk: “My own tears began to flow. He gave me another layer of armor.”

“We have come as far as we’ve come by faith, and our timeless, transcendent values,” she said. “And I mean more than ‘having them;’ I mean ‘living them,’ and refusing to allow a gap between the promise of our ideals and the reality of our times.”

Noting that she had been called to the Cleveland campus to reflect on King and the holiday, Hunter-Gault brought her audience to its feet to sing, ‘Ain’t Nobody Gonna Turn Me Around.”

She looked out past the lectern and made eye-contact around the room: “As a citizen, as a journalist, as a child of the Civil Rights movement, let me exhort you not to leave it alone until next year.”

“Why are we addicted to hate in America?”

That was the simple, provocative question of Rachel Lyon, as she introduced her 2014 documentary to a crowd at the Cleveland Museum of Art. “Hate Crimes in the Heartland” spends an hour exploring two separate, racially motivated killings that occurred nearly a century apart.

The film begins in Tulsa, Oklahoma, following the April 2012 “Good Friday shootings” that took three lives and critically injured two others. Two young men — one white, the other Native American — drove around the city, opening fire on groups of black people. The random slaughter attracted national media attention and stirred the ghosts of another racial atrocity — the 1921 Tulsa race riot.

Rioters obliterated the wealthy black enclave in Tulsa, affectionately known as “Black Wall Street.” Historians still debate what sparked the violence (some say a black man stepped on a white woman’s shoe, others say it was attempted rape), but the outrage of white residents was swift: in fewer than 24 hours, more than 300 people died and more than 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed. Nearly 9,000 black residents were left homeless.

“Hate Crime in the Heartland” features commentary from civil rights activist Jesse Jackson, Harvard law professor Charles Ogletree, Oklahoma NAACP officials and journalists who covered the 2012 shootings. But the survivors of the 1921 riots, only children when their town burned around them, provide the most moving portions of the documentary.

Dr. Olivia Hooker was six years old in 1921. “My grandmother made me these beautiful doll clothes and I remember seeing them burn on the clothesline. My grandmother let me peek out the window. ‘You see those machine guns? That’s your country shooting at you,’ she told me.”

Lyon, who wrote and directed the film, noted that among several race-related massacres in the early twentieth century, Tulsa is best remembered because of an unusual circumstance: Prosperous black residents could afford the cameras that documented the rampage and destruction.

After the screening, Lyon joined a panel discussion that included Rev. Dr. Jawanza Colvin, pastor of the Olivet Institutional Baptist Church; Skyler Edge, an LGBTQ activist; Bettysue Feuer, regional chair of the local Anti-Defamation League; and Rev. Courtney Clayton Jenkins, senior pastor of the South Euclid United Church of Christ.

“I think we underestimate how hard it is to learn from the past,” Lyon said. “Otherwise, we wouldn’t keep repeating it.”

“When we talk about race, we tend to use words that make us comfortable,” comedian W. Kamau Bell told a crowd assembled at John Carroll University. “Words like ‘minority,’ ‘Caucasion,’ ‘colorblind.'” He paused. “We won’t be using any of those words tonight.”

Dressed in a button-down shirt and dark pants, Bell paced leisurely in front of roughly 200 students, community members and administrators as he presented “The W. Kamau Bell Curve,” the keynote of the university’s Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. celebration.

His talk — subtitled “Ending Racism In About An Hour” — was born of frustration in 2007. Bell’s comedy career was stalled, so he rented a theater in San Francisco to present a one-man show. It would be easier, in Bell’s estimation, to talk about race in a theater than a comedy club. His show caught comedian Chris Rock’s attention and landed Bell a show on FX, with Rock as executive producer. Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell ran 64 episodes before its cancellation in 2013.

His “Bell Curve” show may be more than seven years old, but the material is still crisp. Bell sprinkles in breaking news and fresh controversies, making his remarks zing.

Born in Palo Alto, California, Bell moved a lot as a child. His reluctance to make new friends (he figured there was little point) helped him become comfortable being by himself. Young Kamau would immerse himself in comedy specials by his idols, including Eddie Murphy. Building off such influences and adding his own physicality, Bell carved a niche in political comedy, a space he doesn’t always claim as his own. “If you’re black and have opinions and those opinions don’t rhyme, then you’re political,” Bell told Buzzfeed in a 2013 profile.

At six-foot-four, Bell was described in Buzzfeed as “a born sloucher.” In truth, Bell writes in Vanity Fair, he slouches to make himself appear smaller and less threatening.

Now in his early forties, Bell’s humor is piercing and current. Performing less than 15 miles from the spot where police shot and killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice in November, the comedian said “I was excited to see my black president say something. He hasn’t stepped up the way black people would like him to. But it doesn’t matter because we have to defend him due to the racial attacks leveled at him.”

On the John Carroll campus, Bell swung from topic to topic, riffing on diversity in Congress and secret black people meetings (“Don’t worry,” he told a couple black women in the front row, “I won’t tell them where the meetings are.”) He was quick to feed off crowd reaction, and to experiment with new jokes along with the tried-and-true.

Midway through his set, he listed racial words that are too soft, taking particular offense to the word “post-racial.”

“I can disprove the idea of post-racial in two words — Cleveland Indians,” Bell said to applause. “Do Native Americans get any benefit from that? Do they get 10% off tickets? No? Why can’t we just be respectful?” He added: “We wouldn’t name a team the Golden State Arabs . . . Wow, look how quiet it got in here.”

Bell’s take-home: American demographics are changing rapidly, and it’s time to get real about racism. “By 2050, the U.S. will be 30% Latino,” he said. A sole Latina clapped enthusiastically in the back of the auditorium. “That’ll be a lot louder in 2050,” Bell quipped.

Bell ended the evening by transitioning his set to his own family. He told the audience that his two children have given him a fresh lens through which to view himself. “When I first saw my daughter, I knew it was the first time somebody looked at me and didn’t think of me as black. I was just dad. Or, the one without the milk.”

Shakyra Diaz, policy manager for the ACLU of Ohio, asked everyone in a crowded meeting hall who knew someone with a criminal conviction to raise a hand. Almost every person – mostly youth – lifted an arm overhead.

This was a respectable crowd – a City Club of Cleveland forum – and the arms aloft were eloquent. “The land of the free cannot be the land of the lock down,” Diaz said, and a junior at Gilmour Academy jotted the sentence in pencil on her program.

The note-taking at “A Conversation on Race” at the City Club youth forum was no accident. The urgency of police killings in Ferguson, Staten Island and Cleveland had drawn a crowd. Panelist and poet Basheer Jones challenged the hundreds of high school and college students assembled: “There is more we can do. Come prepared to write things down. You won’t remember everything said today. Teachers, have their students bring their weaponry. An African proverb says: ‘Do not build your shield on the battlefield.’”

Diaz and Jones were joined at the front of the room by Jonathan Gordon, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University, and Andres Gonzalez, police chief of the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority.

“Cops, we don’t always get it right,” said Gonzalez, the first Hispanic chief of police in the Northeast Ohio County. “That’s true….A police department is only as strong as the community allows it to be. When the community loses faith in the department that is almost the beginning of the end.”

Diaz zeroed in on system inequity: Cleveland is the fifth most segregated city in the United States; Ohio is sixth in its incarceration rate; fourth for incarcerating women. “This country is number one in the world for incarcerating adults and children,” she said.

Gordon brought forward Michelle Alexander’s groundbreaking book, “The New Jim Crow,” which examines a system that has now put more African Americans behind bars than there were slaves in 1850 before the Civil War. Jones stressed that the students in Collinwood and Glenville High Schools struggle in dilapidated buildings while the new juvenile detention center gleams like a “Taj Mahal.”

Metal detectors in schools condition students for prison, Diaz said, and schools that lack soap and toilet paper telegraph a lack of worth. All this connects, she said, to the Black Lives Matter movement.

When one student asked how to respond to those who claim they don’t see color, Diaz replied curtly: “That’s a lie. If you can see, you see color. What we shouldn’t do and cannot do is deny human dignity.” Echoing Ta’Nehisi Coates, who spoke at the City Club in August, Jones said, “The worst part about racism is that it creates self-hatred; some look in the mirror and don’t like what they see.”

Jones challenged the students to make sure their younger brothers knew more about the ABCs than Waka Flocka lyrics, more math than Usher. He stressed the importance of allies, noting that among the 30 Clevelanders he organized to go to Ferguson were Jews and Hispanics while “there are people in your community who look just like you who are working toward the destruction of it.”

Gordon underscored the importance of action, starting with the reformation of the Cleveland police department. He pointed to the good work of Facing History and Ourselves and the students at Shaker Heights High School who have battled racism. AutumnLily Faithwalker of Laurel School said she wished the panel, while strong, had focused more acutely on what exactly could be done.

Little is more urgent, Jones said. “If not addressed, these issues we are dealing with right now will be the downfall of our country.”

by Terry Pederson

If you dreaded English class and still stumble over there, their and they’re, then Steven Pinker’s “The Sense of Style” may not be the best use of your leisure time. But if you love the English language – if you approach it with reverence, if you delight in translating thoughts into words – then jump right in and enjoy the ride.

Subtitled “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century,” this book refutes the popular notion that the Internet is systematically destroying the language and our ability to clearly express ourselves on paper or screen. In fact, self-appointed scolds have been deploring the perceived decline in proper usage for centuries, as Pinker documents in a series of citations dating to the invention of the printing press.

Conversely, Pinker believes that evolving linguistic standards keep English vibrant and relevant. Far from an inflexible purist, Pinker – chair of the Usage Panel of the American Heritage Dictionary and an Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards juror – generally embraces this progression. He notes that 10,000 new words and word senses made it into the dictionary’s fifth edition, published in 2011.

Yet the real value of Pinker’s new book lies less in refereeing the incessant grammar wars than in probing the magic that permeates fine prose. All writers, he maintains, labor under the curse of knowledge: “a difficulty in imagining what it is like for someone else not to know something that you know.” Hence the impenetrable, jargon-filled corporate announcement or the pompous academic paper that defies understanding. Skillful writers know how to surmount the curse of knowledge.

Proper grammar, word choice and punctuation are potent weapons in this struggle, but Pinker’s opinion of what is acceptable today can seems arbitrary. Thus, he sanctions the increasingly common “comprised of,” which grates on the ear of many a careful writer who believes that the whole comprises the parts, while he nitpicks “parameter” as a synonym for “boundary.”

Such quibbles aside, Pinker is persuasive and writes exceedingly well, enlivening his text with references to that renowned linguistics expert, humorist Dave Barry, and colorful examples of syntactic strife, like a Yale student’s news release advertising “a faculty panel on sex in college with four professors.”

“The Sense of Style” is an entertaining romp with a contemporary message about the timeless gift of clear, graceful writing.

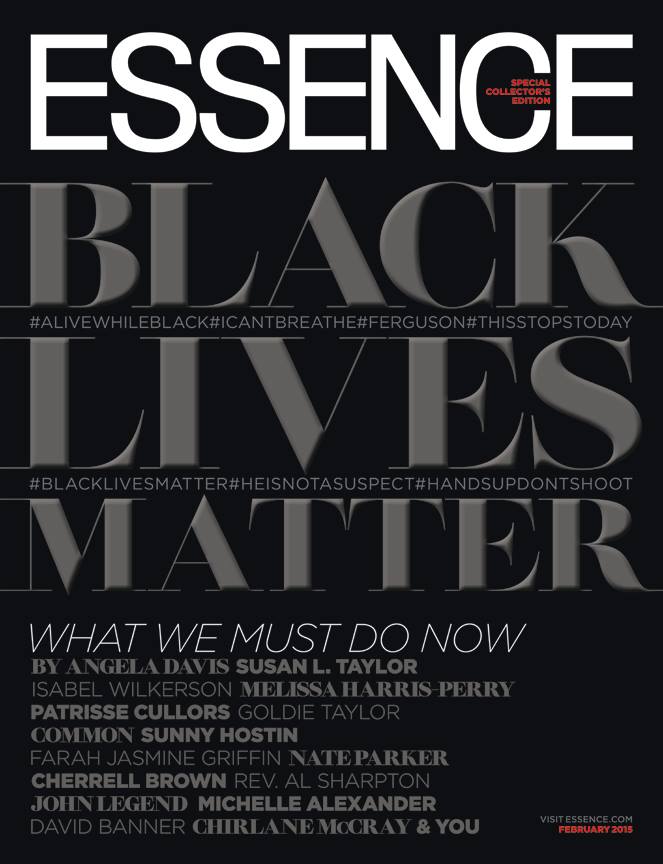

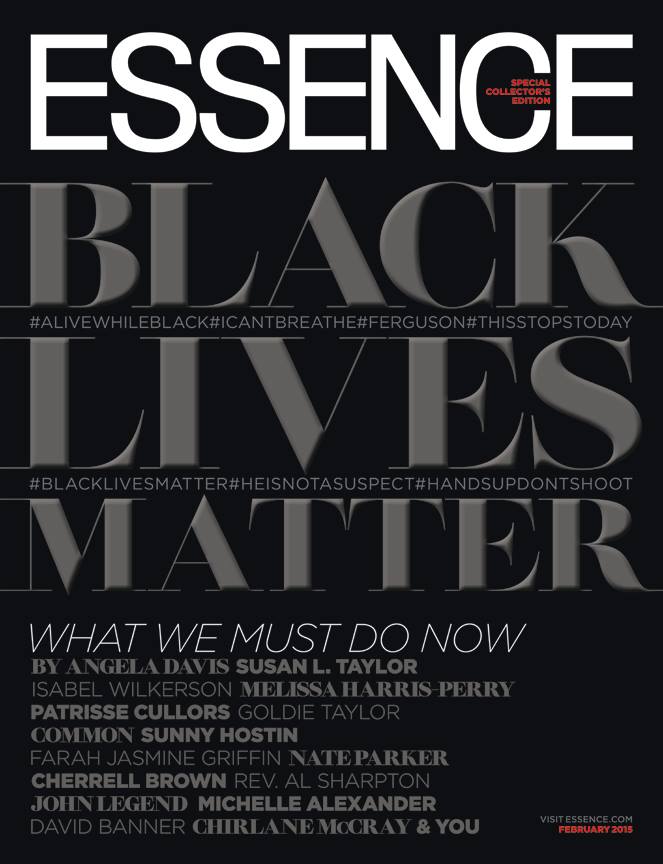

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.

Instead, the African-American publication has dedicated its February 2015 issue to “Black Lives Matter,” the social justice movement that has ignited in the wake of the killing of unarmed black people by law enforcement.

“Pictures are powerful, but so are words,” editor-in-chief Vanessa DeLuca writes in her Letter from the Editor. “After I spoke with the editorial team — with all our souls aching for answers — we knew immediately what we had to do: Tell the story of this tipping point in our history in America. So this February we are focusing our attention on the daring modern-day civil rights movement we are all bearing witness to and making a bold move of our own: a cover blackout.”

Instead, the magazine features essays from MSNBC host Melissa Harris-Perry, The New Jim Crow author Michelle Alexander and Isabel Wilkerson, author of The Warmth of Other Suns, which won an Anisfield-Wolf prize in 2011 for nonfiction.

“We must love ourselves even if — and perhaps especially if — others do not,” Wilkerson writes. “We must keep our faith even as we work to make our country live up to its creed. And we must know deep in our bones and in our hearts that if the ancestors could survive the Middle Passage, we can survive anything.”

This issue will be available on newsstands January 9.

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.

For the first time in its 45-year history, Essence magazine will not use a cover model.