Almost a year before Matt de la Pena won the latest Newbery Medal—the highest honor in children’s literature—he told National Public Radio that his picture book about a young boy riding a bus with his grandmother wasn’t a story about diversity.

“That’s very important to me,” de la Pena told NPR. “I don’t think every book has to be about the Underground Railroad for it to be an African-American title.”

This observation from the author of “Last Stop on Market Street” drew an emphatic Amen from Professor Michelle H. Martin, the Augusta Baker Chair in Childhood Literacy at the University of South Carolina.

“I find it encouraging that this award winner tells a quiet story about an African American boy’s day in the city with his Nana that isn’t about 1) slavery, 2) the fight for civil rights or 3) famous black Americans, because if you strip those children’s and YA books out of the American literary record, you have a paltry list left,” Martin told a gathering in Cleveland. “We need more books like ‘Last Stop on Market Street,’ ‘One Word from Sophia’ and even Ezra Jack Keats’ 1965 ‘The Snowy Day’ that are about the dailiness of being a child of color in America.”

Martin delivered a pointed and eloquent case at the Schubert Center for Child Studies of Case Western Reserve University. She titled her remarks, “Brown Gold: African American Children’s Literature as a Genre of Resistance.”

Turns out that Toni Morrison, Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes—all Anisfield-Wolf winners—also wrote children’s books. So did Alice Walker, bell hooks, W.E.B. DuBois, Nikki Giovanni, Maya Angelou and James Baldwin, according to the research of Cara Byrne, newly awarded a doctorate in English from Case Western Reserve.

Martin focused her remarks on the groundbreaking children’s books of Langston Hughes and his collaborator Arna Bontemps. They published “Popo and Fifina: Children of Haiti” in 1932. This book, she noted, “combats the prevailing notion that black Americans and those in the African Diaspora spoke broken English reminiscent of slavery, that they were shiftless and lazy and that their broken families left their children to their own devices”—all tropes that still bedevil the white imagination.

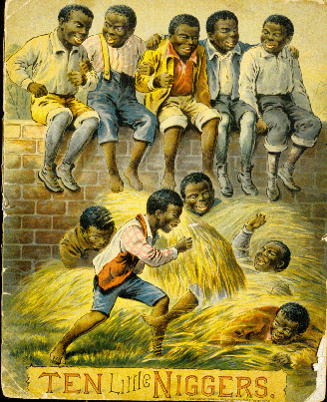

Before Martin began her talk, she played a tinny recording—featuring a woman’s soprano and then a man’s tenor—merrily singing “Ten Little Nigger Boys,” a nursery rhyme tittering about the annihilation of black children. It was enormously popular among whites until the mid-20th-century, showing up in stage plays, minstrel shows and on Ebay today. It stands with “A Coon Alphabet” and other children’s books so violently racist that their covers and content drew gasps from Martin’s audience.

Watching and listening seemed like a corollary to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ now famous observation in “Between the World and Me,” addressed to his son: “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body – it is heritage.”

For Martin, “African-American children’s literature has always been a genre of resistance.” She cited “Clarence and Corrine” and “The Brownies’ Book Magazine” as vital counter-stories that “resist by telling from the inside and inviting readers to understand, not mock.”

But while the quality of literature produced by African Americans and other writers of color is often “tremendous,” Martin said, “the quantity is still shamefully low.” She offered numbers to illustrate this state of affairs:

Nearly 40 percent of American children are non-white and almost half under the age of five are children of color. But among the 3,500 titles sent to the Cooperative Center for Children’s Books in 2013, less than three percent were about black people and less than two percent were written by black authors.

Martin presented three tools to combat the status quo:

- Buy books by and about people of color

- Raise readers

- Openly challenge summer reading lists and book stores and libraries to feature stories that are, in the words of Rudine Sims Bishop, mirrors, not merely windows.

“I have a 12-year-old who reads on a 12th grade level, who ‘eats’ books on her own, but her dad and/or I read to her every night,” the professor said. “It’s the best way to improve her ‘ear reading’ and to expose her to books and genres she isn’t yet willing to venture into on her own.”

A recent study by the Packard and MacArthur Foundations found that the average middle class child enjoys 1,000-1,700 hours of one-on-one picture book reading, compared to a low-income child’s total of 25 hours.

Deborah McHamm, president of A Cultural Exchange, stressed that not all books containing a brown face are worthwhile, and that reading is a political act. “Let’s remember,” she said, “that it used to be against the law for black and brown children to read.”

John Newbery, a printer who is said to have invented children’s literature in 1774, took as his motto the Latin “delectando monemus” or “instruction with delight.” Martin suggested that the phrase is still pertinent in crafting books that benefit all children, as de la Pena accomplished in his Newbery book.

It also requires mindfulness to do so.