“Call soul food what it is: the edible scripture of the Black aesthetic, the culinary answer to jazz, memory food of a people.”

That’s a tweet from Michael Twitty, a culinary historian from Maryland, who sees Cleveland as “the deep north.” To stay warm, he kept on his light grey jacket as he addressed the audience at the Cleveland Natural History Museum gathered for his December talk, “A Place at the Table.”

He begins with a question: “What if the enslaved could tell their story through food?” The story of American history, he argues, lies within the story of the foods people in bondage ate and the meals they cooked for others. It grieves him that so many hadn’t been properly acknowledged or recorded.

Via his food blog, AfroCulinaria.com, Twitty seeks culinary reconciliation. He has poured years into researching the origins of Southern cuisine and the agricultural connections between West Africa, the Caribbean and North America. His tweets at @KosherSoul are just as rich.

A childhood trip to Colonial Williamsburg sparked young Michael’s interest. The splendor of the kitchen in the Governor’s Palace fascinated the 7-year-old foodie. “My father was a Vietnam vet and all he wanted to see was guns and the cannons going off,” he said. “I had him in the kitchen for an hour and a half, staring at this beautiful pheasant. . . I actually flirted with the pheasant.”

It’s fitting then that the Twitty family – both living and ancestral — features prominently in his work. He started The Cooking Gene, a crowdfunded culinary tour of the South, five years ago, as he traced his family tree through two centuries. Along with a host of scholars and chefs, he visited the lands they worked and in some cases, sought to meet the descendants of the people who owned them.

Twitty’s first book, of the same name, will arrive in 2017. A few prospective publishes worried that Twitty’s identities – a black, gay, Jewish man – would be too much for readers. “This country is the only place I’m possible,” he retorted. “How dare you deny me the one thing America can give me – my uniqueness. My possibility.”

When Twitty hosts cooking demonstrations on former plantations and historical sites, he dons the full 18th century attire of those in captivity. He uses tools that would have been readily available to that population – cast iron skillets feature heavily – and recipes that would have been intimately familiar to the enslaved people on the plantation. Think okra and rabbit soup or mashed black eye pea fritters.

From the lectern in Cleveland, Twitty was careful with his language. He mentioned “enslaved people,” not slaves. “Slaveholders,” not master. They were “freedom seekers,” not runaway slaves. “Better yet, patriots,” he insisted. “Not slave rebels—patriots. They only wanted what America promised.”

In his work as a culinary historian, he has mastered the art of preserving culinary history, deftly maneuvering his way around a reluctant elder to slowly ease down their guard as he tries to capture their recipes. His first tip? Present yourself as a helper, not a pest. “Don’t be lazy; do some work. Wash the dishes, sweep the floor,” Twitty advises. Only then can you sidle up with questions about ingredients. Another tip? “Keep some measuring spoons in your pocket.” All the better to measure what the elders tend to eyeball.

He also brings dearly won kitchen wisdom to our political moment: “With these incidents of hate that we see, we have a choice. And that choice is to feed people. Feed them knowledge. Feed them love.”

Rita Dove is coming home.

The former poet laureate and Akron native will return to the region that raised her to celebrate her new “Collected Poems” and for the 30th anniversary of her Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry collection, “Thomas and Beulah.”

“An Evening with Rita Dove & Friends” serves as an intellectual appetizer for our 2016 awards ceremony, with jury chair Henry Louis Gates and all five 2016 winners — Rowan Ricardo Phillips, Mary Morris, Orlando Patterson, Lillian Faderman and Brian Seibert — scheduled to attend. Poet Toi Derricotte, who won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for “The Black Notebooks” in 1998, will introduce her friend to a hometown crowd.

The evening is co-sponsored by Brews and Prose, the literary series.

Published in 1986, “Thomas and Beulah” is based loosely on Dove’s maternal grandparents and is set in Akron. It traces their lives through the birth of her grandfather Thomas in the early 20th century until the death of her grandmother, whose actual name was Georgianna, in the 1960s.

“This is the quintessential moment to celebrate Rita Dove in her beloved community,” said Karen R. Long, manager of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards for the Cleveland Foundation. “She has served more than 20 years as an indispensable juror, and she has elevated American literature with her poems and teaching and editing. For most of us, that began with ‘Thomas and Beulah,’ which brought a black, middle-class, mid-American couple into our collective literary consciousness.”

The celebration begins at 7:30 p.m. on September 14 in the Maltz Performing Arts Center on the Case Western Reserve University campus. Tickets are free and parking is $7. Tickets for parking and for the event are available here or by calling 216-368-6062.

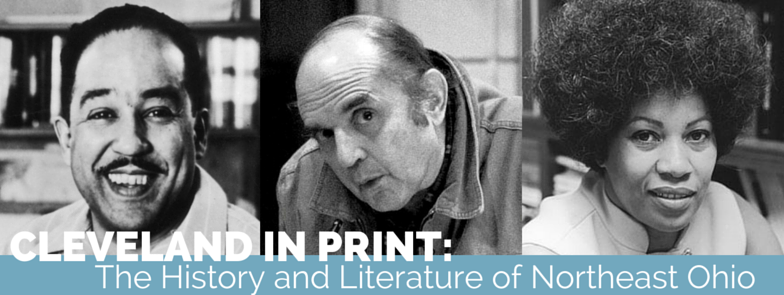

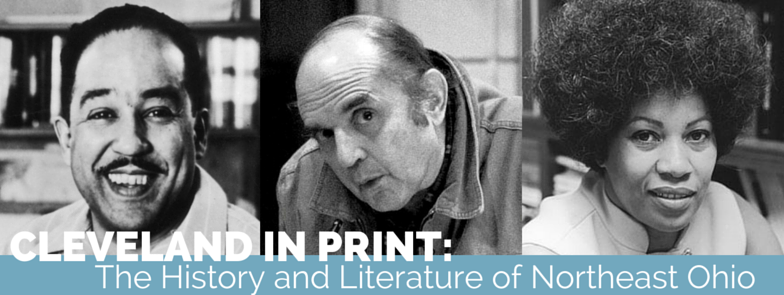

Come learn more about the Cleveland that helped shape Langston Hughes, Toni Morrison, and Harvey Pekar. Teaching Cleveland has teamed up with Literary Cleveland and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards to present “Cleveland in Print: The History and Literature of Northeast Ohio” on Thursday, January 28.

The story of Cleveland in the 20th Century is one of immigrants and migrants, racial tensions, and economic stratification. Join us as we examine three works by these three Northeast Ohio writers and explore the interplay between person, place and perspective; bring a notebook or a laptop and explore your own connections as well.

A light dinner will be served, and participants will receive a book, compliments of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards.

“Here is a unique opportunity to reflect on transcendent American literature tied to the 216,” said Karen R. Long, manager of the book awards. “I have enormous respect for the work of Greg Deegan and Arin Miller-Tait as innovative educators and founders of Teaching Cleveland, and Lee Chilcote for his initiative in bringing Literary Cleveland onto the scene. This night should be worth everyone’s time.”

Register for this event here. We’ll see you on the 28th.

Toledo attorney Lafayette Tolliver, 65, estimates there were fewer than 300 black students on the campus of Kent State University during his four years a half-century ago. “We pretty much knew everyone there because that’s how few of us there were,” he said. “We were there, we did it, we graduated. It was quite an exhilarating time.”

Interested parties can glimpse that mid-American black student experience in a new photography exhibit, “Coming of Age at Kent 1967-1971: A Pictorial of Black Student Life.” Culled from Tolliver’s personal collection, these images depict a pivotal time on college campuses, as black students at predominately white institutions began organizing for more resources, taking cues from the burgeoning civil rights movement. It was also a pivotal time at Kent – the National Guard shot four unarmed students May 4, 1970.

When Tolliver arrived in 1967 to study in small-town Kent, the student-founded organization Black United Students was beginning to solidify. “We were looking to have immediate impact,” Tolliver said, ticking off their goals: more black professors, larger black enrollment, more black studies courses. Their overarching goal was to “make it less of an isolated experience for students.”

Young Tolliver worked on staff for the college yearbook and daily newspaper, majoring in photojournalism. “I was the only black student taking pictures of black life. Whenever you saw me, you saw my camera,” he recalled. He graduated in 1971 with his bachelor’s in journalism, but the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. shifted his career ambitions to law: “I wanted more leverage.” He attended law school at the University of Toledo and practices mostly discrimination, civil rights, and bankruptcy law.

Earlier this year, Tolliver gave the university thousands of negatives from his collection; archivists selected more than 30 to display at the Uumbaji Gallery in Oscar Ritchie Hall. He hopes it will inspire more people to dig into the archives for similar historical context.

“I just wanted to make sure somebody documented this life that we were going through,” Tolliver said. “I wasn’t just taking pictures for my personal use. I wanted to have a record: we were there and we made an impact.”

The exhibit runs from October 11 through October 23, and is free and open to the public. Tolliver will give remarks at a reception 11 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. October 18 during Homecoming Weekend at Oscar Ritchie Hall on the KSU campus. To register, visit bit.ly/tolliver.

Anthony Marra startled the literary world in 2013 with his stunner of a debut, A Constellation of Vital Phenomena. His fresh, Chechnya-inspired book won this year’s Anisfield-Wolf Book Award and will bring its author to Cleveland for the first time. He follows in the footsteps of Iraq War veteran Kevin Powers, who spoke last year about his own war novel, “The Yellow Birds” on the campus of Case Western Reserve University.

Marra, 30, will speak and read at 4:30 p.m. Wednesday, September 10, in the intimate setting of the Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities at Case. “Wars shatter families, relationships, even stories,” Marra has said. “But Constellation is less a story about war than a story about ordinary people rebuilding their lives during and in the aftermath of war. It’s a story not about rebels and soldiers, but about surgeons, nurses, and teachers, each of whom tries to salvage and recreate what has been lost.”

.

The writer first found his way to the Caucuses as an undergraduate abroad. He grew up in Washington, D.C., and now lives in Oakland, Calif., and teaches at Stanford University. His novel, set over five days between the two modern Chechnya wars, has many sources in nonfiction and fiction. One is to the work of assassinated Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya; another is the Anisfield-Wolf winner Edward P. Jones.

In crackling scenes flecked with notes of mordant humor, A Constellation of Vital Phenomena contains six central characters, and begins with an 8-year-old girl hiding in the forest as the Russian federals burn her home and “disappear” her father. A neighbor determines to hide the child in a mostly-destroyed hospital where one doctor and one nurse remains. “When I traveled to Chechnya,” Marra remarked, “I was repeatedly surprised by the jokes I heard people cracking. It was a brand of dark, fatalistic humor imprinted with the absurdity that has become normalized there over the past two decades.”

The novel won the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize, and was long-listed for the National Book Award. Marra earned his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and studied with novelist Adam Johnson at Stanford. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Republic, Narrative magazine, the 2011 Pushcart Prize anthology, and the Best American Nonrequired Reading 2012.

The Baker-Nord event is free and open to the public, but registration is required. Get more information and RSVP for the event HERE.

Poet Adrian Matejka mixed his love of boxing with his love of literature to produce “The Big Smoke,” 52 poems that center on Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight champion. The collection won this year’s Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, and was a finalist for the Pulitzer and the National Book Award.

On September 10, Matejka will bring his words to the Cleveland canvas of the Old Angle Boxing Gym while boxer Roberto Cruz, 11, and Corey Gregory, 42, will each demonstrate the sweet science in separate demonstration bouts. We are proud to collaborate with Old Angle owner Gary Horvath and Dave Lucas of Brews + Prose to welcome the Clark Avenue neighborhood, the boxing community and local literati for a memorable night of sport and poetry.

The evening begins at 7 p.m. and is free. The public is welcome, with registration details available at the event’s Facebook page. Matejka, a professor at Indiana University, will also take audience questions and sign books. He spent eight years researching the storied and much-mythologized life of Johnson before creating the poems—told in the voices of the boxer and the people around him.

“There is a wonderful recording of Johnson narrating part of his 1910 fight with Jim Jeffries,” Matejka told Shara Lessley of the National Book Awards. “As Johnson describes the action, his cadences emulate the fight action in a way that makes him sound like a ring announcer. I used the recording as one of the primary sources for Johnson’s ‘voice’ in the book.”

Matejka, 42, said some of his work, particularly the sonnets, reflect the physicality and cadences of the sport. “The Big Smoke” ends in 1912, a full 34 years before Johnson died. Matejka plans a second volume of poems on the man who, he says, “managed to win the most coveted title in sports, but through the combination of his own hubris and the institutionalized racism of the time, he lost everything. That rise and fall naturally lends itself to the oral tradition of poetry.”

Anti-racism activist Tim Wise joked that he was on his third visit to the University of Akron campus in the past 15 years and was pleased to see the audience increase each time.

Wise, 45, opened the evening by taking note of his privilege as a middle-class, college-educated, heterosexual white man. “I’m here because I fit the aesthetic for what’s necessary for white people to talk about racism in America,” he boomed. “People of color get up and say it all the time, but they get ignored. The real measure of post-racial America is when a black person can stand here and receive the same reception I do.”

Acknowledging his privilege is the cornerstone of Wise’s career. Born in Nashville, Tennessee, he received his B.A. from Tulane University, where he led an anti-apartheid student group. In the early 1990s, he moved south to become a coordinator for the Louisiana Coalition Against Racism and Nazism, whose mission was to extinguish the political future of white supremacist, David Duke. Wise moved on to community organizing in New Orleans’ public housing, and to work as a policy analyst for a children’s advocacy group.

His 2005 memoir, White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son, still sells briskly. It also still fuels debate on the soundness of a white man’s prominence in the anti-racism movement, endorsements by Angela Davis and Cornel West notwithstanding. And White’s public speaking habit of shifting into “white” voice to contrast with his “black” voice can be cringe-inducing.

Still, if there were critics tucked into the Akron crowd of 500 at E.J. Thomas Hall, they stayed quiet. Several African-Americans nodded vigorously as Wise laid out his points. “You can’t solve social problems with silence,” he argued. “I invite white folks to have the difficult conversations.”

Structural inequity should bother everyone, Wise said, and as the country’s demographics shift toward majority-minority, equality is more important than ever. “What binds us as Americans?” Wise asked the crowd. “It’s the myth of meritocracy — that anyone can make it if you try hard enough.”

Wise argued that this simplistic dogma ignores reality. “Here’s one fact for you: 500 white people in this country have the same accumulated wealth as 41 million black people,” Wise said. The crowd fell silent. “If you think that’s because those 500 people just somehow worked harder…no amount of education will help you.”

Wise swiveled his focus to a 1963 Gallup poll, when two-thirds of white Americans believed that blacks had equal opportunity for fair housing, education and employment, even as the civil rights movement was bubbling to a fever pitch.

Wise didn’t hesitate in calling such respondents out. “They were delusional,” he said, voice rising. “But there wasn’t any penalty for being ignorant of black and brown issues. It’s not on the test. Whatever white folks think is important, black people have to learn that. That will damn sure be on the test. White folks write the test. That’s the luxury of being the norm.”

Junot Diaz did not dress up for his talk. He wore black jeans, worn boots and his white shirttails out beneath a charcoal sweater, front and back. On an October Friday afternoon, he walked into the terraced auditorium at Cleveland State University, and leaned companionably against the wall, sipping coffee out of a disposable cup as Professor Antonio Medina-Rivera introduced him.

Medina-Rivera ran through Diaz’s dizzying credentials: a full professor at M.I.T., a 2012 MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellow, a Pulitzer Prize for his vibrant first novel “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” which also won an Anisfield-Wolf book award. In addition, his host reported, Diaz volunteers at Freedom University, a new institution that attempts to meet the needs of undocumented college students in Georgia.

The 44-year-old Diaz took the stage and gradually built a case for embracing ambivalence and imperfection. “I am never trying to be right,” he said. “I’m trying to be the launch pad for somebody to be righter.” He mocked the preening persona-building on Facebook. He smiled and joked, even as he delivered some withering political remarks. Here is one sample:

“The elites are running rough-shod over us. They are engineering forced income transfers to the top. Elites are gutting the middle class, and that gets a shrug. But say, ‘A Mexican is taking your job,’ and everybody has an opinion.”

Diaz read the same passage from “Oscar Wao” that he selected in 2008 when he appeared at the Cleveland Public Library: three pages at the start of Chapter Two that describe Oscar’s sister Lola called to the bathroom by their mother to feel for a lump in the matriarch’s breast. It is a gorgeous passage, and one of the few stretches in the book without profanity or explicit sexual asides.

When Diaz finished, a student asked him if he thinks in Spanish. The writer was born in Santo Domingo, a third child in a neighborhood without electricity. His mother brought him to Parlin, N.J., to rejoin his father when he was six.

“Spanish is my birth language, and everything that means,” Diaz answered. “English is my control language, and everything that means. I can’t be super-smart in Spanish. In Spanish, I am less guarded.”

Asked how he perfected Lola’s voice, Diaz observed that poor children come-of-age in front of each other, in packed living quarters. In the comfort of the American middle class, adolescence happens privately behind closed doors.

“Most of us have so many aspects of ourselves, it is almost impossible to reconcile,” Diaz said, recounting his own years pumping iron as a young man, only to be caught out for his nerdy, Dungeons and Dragons-loving side by a dorm mate at Rutgers. There he fell under the literary influences of Toni Morrison and Sandra Cisneros, even as he worked full-time delivering pool tables, washing dishes, and pumping gas to cover tuition.

Diaz poked fun at peers who name Charles Dickens when asked who is their favorite author. He made a point of praising contemporaries – Ruth Ozeki for her new novel, “A Tale for the Time Being,” and Edwidge Danticat for “Claire of the Sea Light” calling it “unbelievable, the best one she has done.” (Danticat won an Anisfield-Wolf award for “The Dew Breaker” in 2005.)

Everyone, Diaz claimed, is searching for the place where “all the parts of us can be present and safe.” For him, that place was reading. “I write because I love books,” he said. “Writing is just my expression of my excess love of reading.”

Still, he warned his listeners against unbridled enthusiasm. “Love something too much and you know the kind of kids you raise. . .

“It is OK to be involved in a practice you are ambivalent about. Some of the best parents are ambivalent about being parents. . . I am deeply ambivalent about the craft of writing. Anyone who grew up in the shadow of the (Dominican Republic) Trujillo dictatorship can’t see stories as only good. There is a cost to everything. I am always aware of the shadows that lurk in every artistic practice, and I’m always troubled by them.”

Then the sober mood broke. In a different conversation, Diaz allowed that he had been texting pictures of Cleveland. He sent one to his buddy Christopher Robichaud, a lecturer in ethics at Harvard’s Kennedy School. Robichaud grew up in Euclid and Chardon, and graduated with a degree in philosophy from John Carroll University. The two men bonded over “tabletop role-playing games, horror movies, superhero comics,” Robichaud said.

And yes, he answered Diaz: the structure the writer photographed was indeed the West Side Market that Robichaud had described in their chats about childhood.

Eugene Gloria says that he is fascinated by failure. He was quick to describe a particular poem or two as failed, and even his book, “My Favorite Warlord,” which won a 2013 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, as a failure of his original idea to describe 1967.

“I ran out of ideas for 1967, became bored,” Gloria told listeners at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland. “I ran out of gas, even though I was obsessed by it. The idea of failure is fascinating to me.”

And yet, 1967 is a fulcrum in “My Favorite Warlord” – the year his family arrived in San Francisco from the Philippines, the year his future wife was born in Detroit, the year that Wole Soyinka is “being hauled to jail/on trumped-up charges” as Gloria writes in “Allegory of the Laundromat.” He told the MOCA audience that he was thinking about soul music as he wrote it.

Harvard University’s Henry Louis Gates, Jr., praised this very poem as he introduced Gloria to the sold-out audience gathered at the Ohio Theatre Sept. 12 for the Anisfield-Wolf awards ceremony:

“What I find so resonant in all of these poems is the idea of multiplicity, that we possess many identities stemming from the many diverse forces that have shaped us,” Gates said. “In Gloria’s case, he is shaped by a Filipino background, though education among the nuns in a Catholic school, to coming of age in the same neighborhood in which he found ‘Janis Joplin shoring up supplies/from our corner Chinese grocer.’”

Gloria, 56, has taught for 13 years at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. He read his poem, “Here, On Earth” for both the crowd at MOCA and the throng at the Ohio Theatre. He told his listeners that it captures his relationship to Indianapolis. The final two stanzas:

Here, on earth we are curtained by rain.

A subset in the far corners floating

toward the center. We are an island

in landlocked America. We are

Thai, Filipino, and Vietnamese.

We are, all of us, post exotics.

At MOCA, Gloria followed a reading from Kazim Ali, an Oberlin College professor who started with his poem “Fairytale.” It concludes, “All the sacred words/are like birds wheeling in the sky./Who knows where they go?” The political nature of Ali’s reading inspired Gloria to start with “Elegy with Ice and a Leaky Faucet.” He called it “one of the oddball poems in my collection; it failed as a political poem.”

And yet “Elegy with Ice and a Leaky Faucet” is many reader’s introduction to Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American man beaten to death on the eve of his wedding by Detroit auto-workers enraged at the ascendancy of Japanese cars in the U.S. market. “The dialectics of fists and ball bats/turned his wedding party into a funeral” Gloria writes.

When Ali and Gloria perched on tall stools together at MOCA, Ali spoke about the context for two of his newest poems, which focus on Bradley Manning, convicted in July for violating the U.S. Espionage Act.

“We are political,” Ali said. “We can notice it or not notice it.”

“Amen to that brother,” Gloria responded. “We try to avoid being cliché. The struggle is taking an overt political position in an art that calls so much attention to language can be problematic. But like Kazim says, we are all political.”

The men riffed on Shelley’s famous maxim that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” suggesting that the “unacknowledged legislators of the world” may well be the secret police.

Before he returned to Indiana, Gloria said, “The idea of identity is always going to be a subject. I have no choice. Identity is so multi-layered and I am obsessed.”

Meet our esteemed manager, Karen R. Long, at the Cleveland Public Library’s Brown Bag Book Club on Wednesday, August 21 at noon.

Long, the former Plain Dealer book editor, will introduce Cleveland to the four 2013 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award winners. Beginning Wednesday, September 4, a more in-depth discussion of each book will occur weekly:

Tickets to the Sept. 12 awards ceremony are sold out, but Long will raffle off six at her library talk.

Karen R. Long served as book editor of The Plain Dealer for eight years before becoming the manager of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Long is a vice president for the National Book Critics Circle, where she is a judge for its six annual prizes, awarded each March in New York City.

Karen will give her talk on the 2nd Floor of the Main Library Building, in the Literature Department. Interested guests will be able to check out the featured books after the talk. Questions? Call the library at 216-623- 2881.

Please call 216-623- 2881 with questions.

Gary Schmidt, the lanky author of winning children’s novels such as “The Wednesday Wars” and “Okay for Now,’ stood up before a dining hall at Kent State University and admitted to choking up early in the day. He had caught a 5 a.m. flight south from Grand Rapids, Mich., where he teaches at Calvin College, to join the Virginia Hamilton Conference, the longest-running event in the United States to focus exclusively on multicultural literature for children and young adults. It is held annually at Kent State in the spring.

Once in his airline seat, Schmidt got out his copy of “First Part Last,” a luminous book by the conference keynote speaker, Angela Johnson. “I’ve taught this book eight times to college classes,” he said. “And I got to the part where Bobby tears up the adoption papers and I start to well up. The people sitting next to me in seats 11 B and C asked if I was alright. They offered to sit with me if necessary.”

Schmidt paused and shook his head. “I was completely humiliated,” he deadpanned. “Thank you for that Angela.”

Johnson, the recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2003 for her own children’s fiction, laughed. When it was her turn at the lectern, she let the audience imagine her at age 15, one year younger than Bobby, the mesmerizing narrator of “First Part Last.” He tells of teen fatherhood from a boy’s point-of-view.

Young Angie was angst-y. She wore a necklace made of razorblades. She stormed around her small town home in Windham, Ohio, threatening her brother with decapitation if he entered her room. Her writings were rejected by the school literary magazine for being too grim, too full of rats in tumbled down buildings. (What the adult Johnson didn’t mention was she was also a Windham High School cheerleader.)

Into this potent adolescent moment came Valerie Barley, “an old Beatnik teacher,” who commanded the attention of her students, including Angie, whose tastes ran to detective stories. “She got us to love the Beats,” Johnson said. “She got us to read about people on the road.”

The audience of about 150 was rapt. Johnson, 51, doesn’t own a car and rarely accepts speaking invitations. She joked that her Kent neighbors perceive her as a wacky character wearing “a hoodie and pajama bottoms” throughout the day.

She claimed to have overhead one woman whispering, “It’s OK. I think she’s a writer.”

That writer’s beginnings predate high school. Johnson said that she “didn’t say much as young child. I was a born listener. I was the child who sat under the table while my aunts talked – full of inappropriate stories, by the way. They’d throw their heads back and laugh and their laughs made me want to tell stories.”

Her first book, “Tell Me a Story, Mama,” started as a manuscript discovered by Cynthia Rylant, of “Henry & Mudge” fame. The older woman met a college-age Johnson when Rylant advertised for child care. The women got to know each other and Johnson remembered shelves of children’s books and “real food in the crock pot.”

Then, unbeknownst to the babysitter, Rylant copied the Mama story and mailed it off to her own publisher. The editor at Orchard Press offered to buy it on the spot.

More than 40 titles later—with three Coretta Scott King awards for “Toning the Sweep,” “Heaven” and “First Part Last”—Johnson still commands a room. In warm, mellifluous tones, she retold a family ghost story for the Kent State audience, describing the red dirt of Alabama caked on the feet of her father as a child. Every table was leaning in.

“Kids and teens are so much more interesting than adults,” Johnson once told the African American Literature Book Club. “Life is happening when you are a teenager. One minute you’re a child, the next you’re allowed to go out in the world by yourself. Who knows what will happen?”

Looking out on the audience in Kent, Johnson said, “I sometimes still feel like a confused teen or a small child stumbling. But the quest goes on, and I write on.”

After a rich discussion between philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah and museum director Johnnetta Cole, the final question in Oberlin’s Finney Chapel was a zinger.

Appiah, who won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 1993 for his influential collection of essays “In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture,” had been turning over questions of identity and art with Cole, an anthropologist who leads the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art. The duo’s last question came from Kelsey Scult, 20, an Oberlin African Studies major, who just completed a January internship at the Northwest African American Museum in Seattle.

Looking at Cole, the white student asked, “If I was up for a job at your museum against someone of African descent, I would think they should probably get the job.”

Without hesitation, Cole told Scult she had asked “an absolutely wonderful question. When you go for the job, I would urge you to identify with all of humanity. And all of humanity came from only one place—the African continent.”

Cole, 76, who grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, said her mother understood something about common humanity. “My mother didn’t have positive experiences with white folk, but whenever she did, she’d say, ‘You know so-and-so, that white man, he must have a touch of color.’ I live for the day when we dwell more on our connectedness than our differences. If you’ve done your work, and you know how to move with respect, then it should be your job.”

Appiah, 58, president of Pen America and a Princeton University professor, agreed. He reminded Scult that the W.E.B. Du Bois sought out white experts in compiling his Encyclopedia Africana, and that museum staffs are not segregated. “Identity is not the main thing that matters in scholarship, although identity does matter,” he said, noting that a cadre of white men weighing the intellectual rigor of women might be suspect.

The February 7 evening in Finney Chapel began with Appiah’s slide show of exteriors of renowned museums. He noted that these institutions were forming during the 19th Century’s infatuation with Romanticism, a reaction to the Enlightenment that yoked artistic expression to nationalism. Appiah argued that contemporary peoples aren’t shed of this link, using an example from the Guggenheim Museum that grouped El Greco and Picasso as exemplars of Spanish art, even when the biographical facts confound such claims.

“One of the great philosophical misunderstandings about art is that it is an expression of a nation, a culture, and not the work of an individual,” Appiah said. This is just as true for literature, which borrows liberally from other wells, as William Shakespeare did from Italian sources, he said.

Cole, who had left the stage for Appiah’s opening remarks, returned to ask him, “If museums did not exist, would it be necessary to invent them?”

Appiah looked slightly startled. “That’s a great question,” he murmured. “The things that museums do, we’d have to do—care for precious objects that come from the past, help interpret them, introduce young people to this great human heritage and research those objects about which we don’t know enough.” He said the key meaning of the arts lies in the act of preserving and passing on the masterpieces worth responding to.

For identities to matter, Appiah said, they must be taken up, interpreted and mediated by outside reactions. He said if he began wearing a dress around the Princeton campus, there might be mild surprise, but little more. A student came to the microphone and challenged him, saying in academics, gender bending would frequently provoke hostility.

Cole, who graduated from Oberlin in 1957, said she was smitten by the student’s moxie. Several times, she circled back to quote an Appiah truism: “Things are always more complicated than they seem, and some complexities we don’t like to confront.” When the same student asked how First World museums, which own stolen objects, justify exhibits that amount to “celebrations of colonialism, exploitation and displacement,” Appiah said the crux was not ownership, but access.

“Not everything that started out in a colonial place was stolen,” he said. “What’s really important is if you live in Mali, you don’t have much of a shot at the cultural artifacts that a person in London or New York or Berlin has a chance to see.” Appiah said he was cheered by some of the lending now from the British Museum to institutions in Kenya and China, whose curators are keen to exhibit not just indigenous objects, but want examples of English and European art to share.

In international exchanges, Appiah noted wryly, “Every threat can be re-described as an offer.”

On December 6, Toni Morrison will deliver the Ingersoll Lecture on Immortality at 5 pm in Sanders Theatre on the Harvard campus. Throughout the fall semester, Harvard Divinity School has hosted a working group on the religious dimensions of Morrison’s writings. Watch the video here.

If you’re interested in attending, tickets may be requested from the Harvard Box Office. Limit of 2 tickets per person. Tickets are available by phone and internet for a fee, or in person at the Holyoke Center Box Office. Call 617.496.2222 or reserve online at www.boxoffice.harvard.edu. Limited availability. Tickets are valid until 5:00 pm on the day of the event.

The event will be live-streamed via a link on the Harvard Divinity School home page beginning at 5:15 pm.

If you are in the area and able to attend, let us know your thoughts on Morrison’s lecture!

We are roughly a month away from the 2012 Anisfield-Wolf ceremony and is customary, we are alerting fans to several opportunities to meet our 2012 winners.

Cuyahoga County Public Library, Beachwood Branch (In the Meeting Room)

25501 Shaker Boulevard

Beachwood, Ohio 44122-2398

Corner of Richmond & Shaker Boulevard

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

7:00 PM – 8:30 PM

Registration is recommended. Click here to register.

Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities (Clark Hall Room 309)

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

4:30 PM – 5:30 PM

This event is free and open to the public.

Registration is recommended. Click here to register.