Huffington Post’s Black Voices rounded up 50 books the editors think every African American should read (they added on Twitter that of course the list has value to everyone, but these books focus primarily on the black experience in America). We were thrilled to see how many Anisfield-Wolf winners were on the list, proving to us once again that our winners stand out in the crowded literary field.

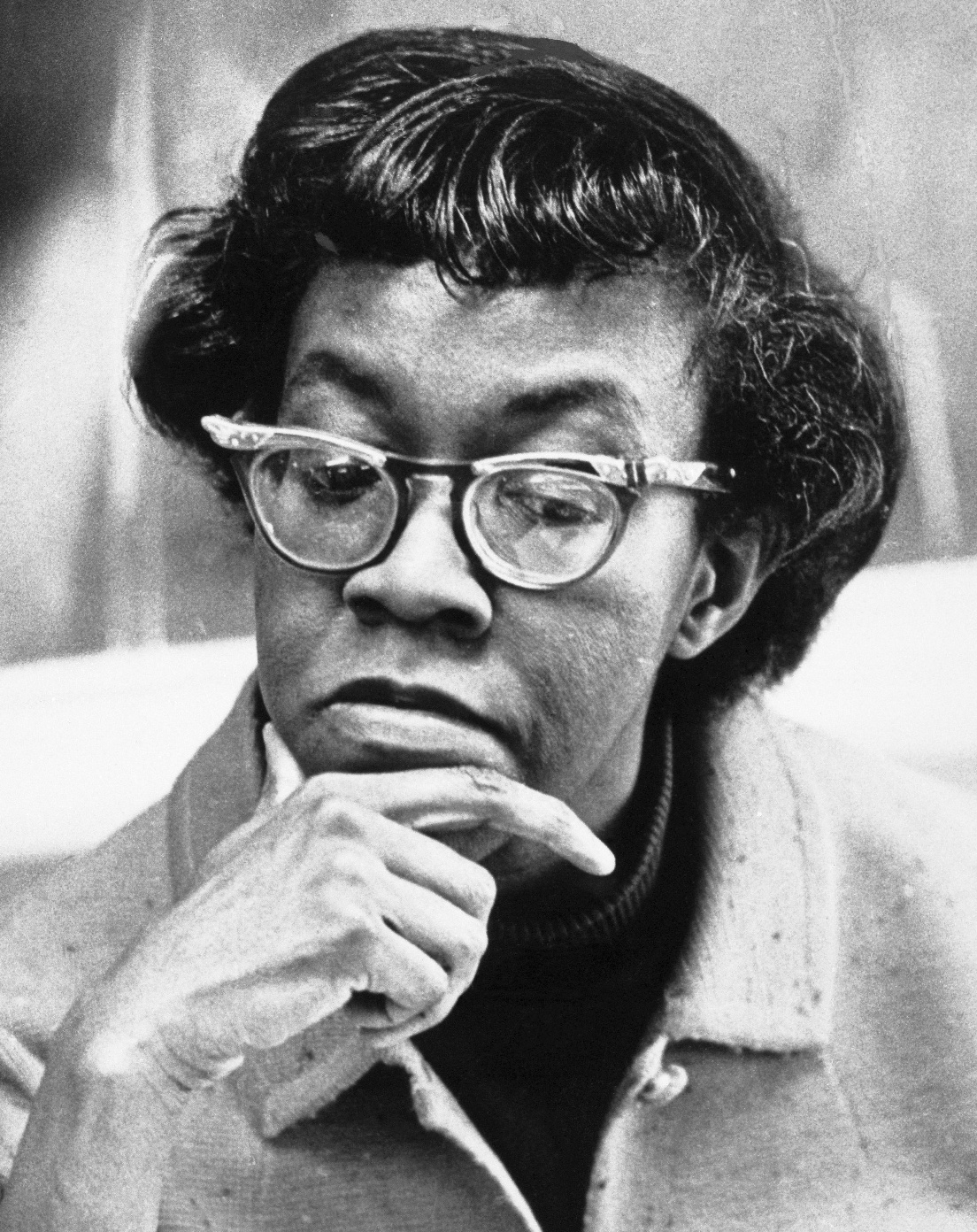

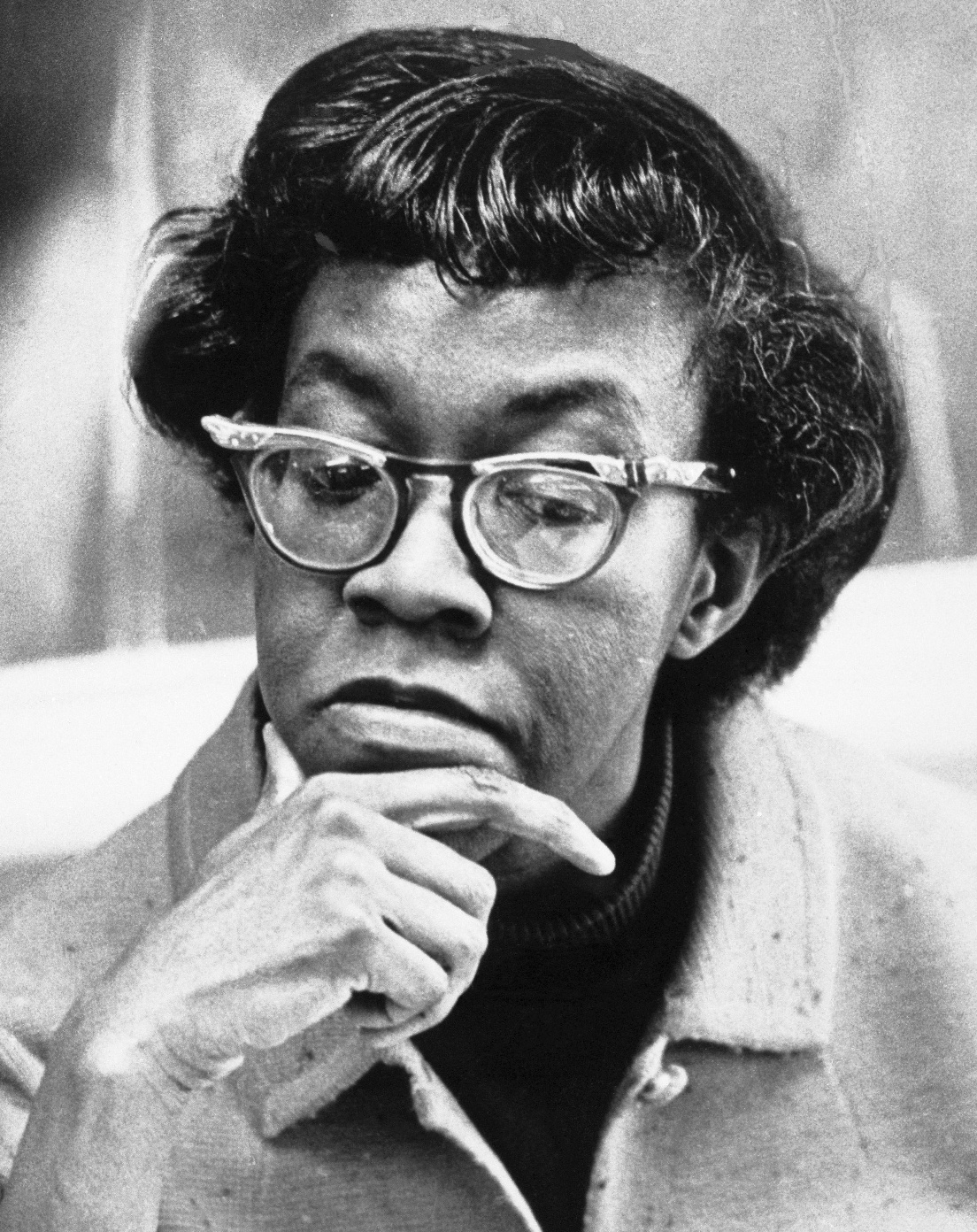

Gwendolyn Brooks

“Annie Allen” (1949)

Edwidge Danticat

“Breath, Eyes, Memory” (1999)

Chimamanda Adichie

“Half Of A Yellow Sun” (2008)

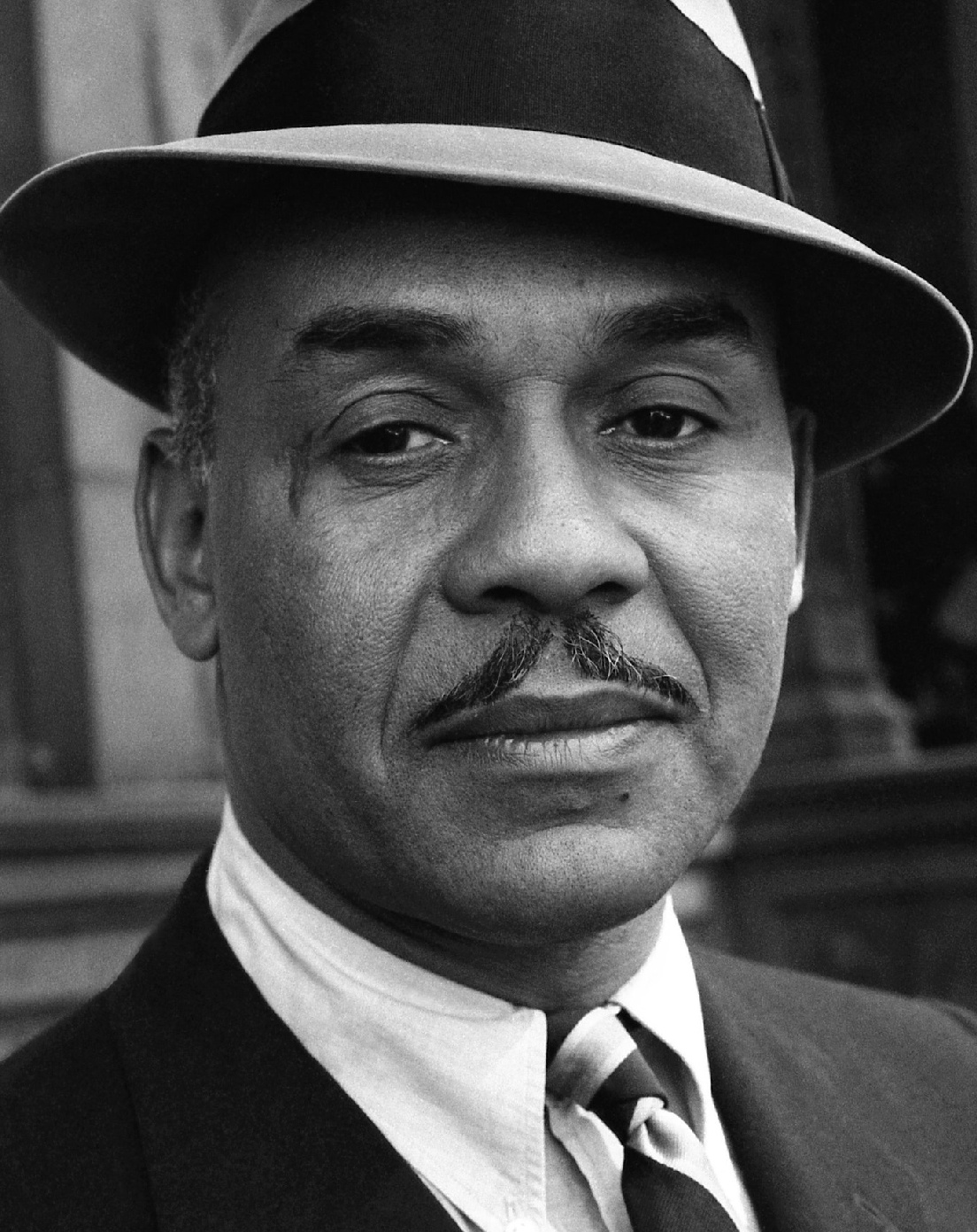

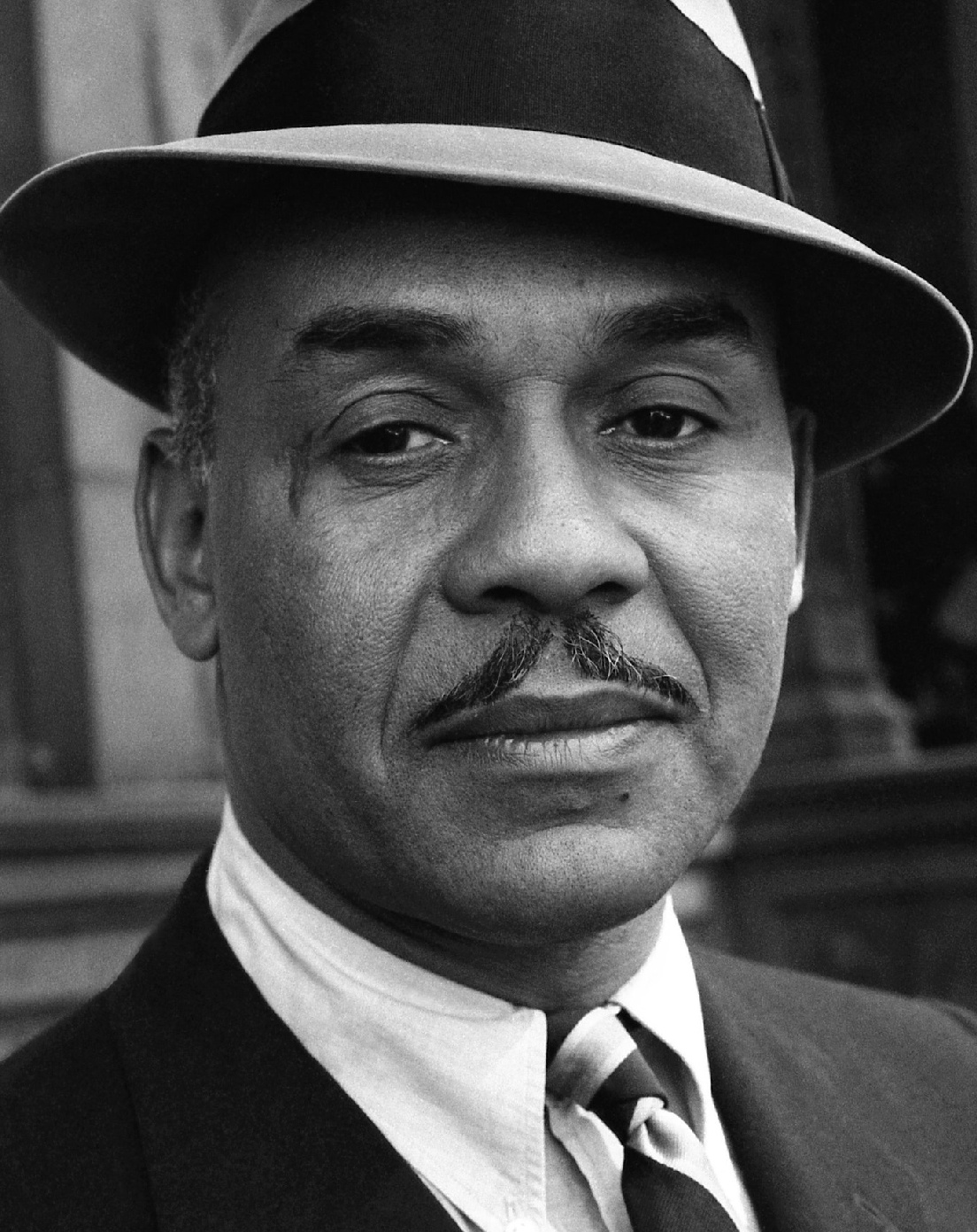

Ralph Ellison

“Invisible Man” (1952)

Edward P. Jones

“The Known World” (2003)

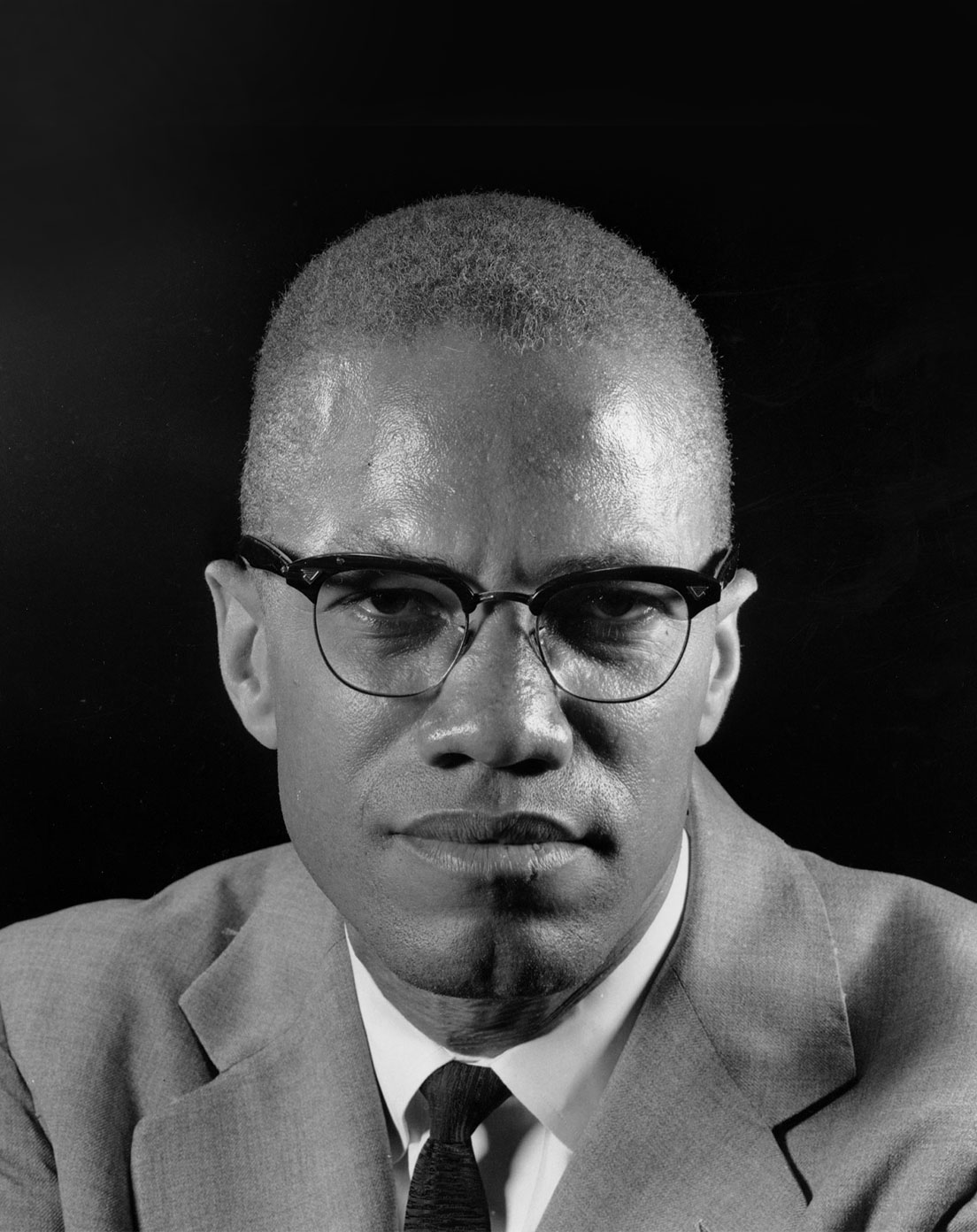

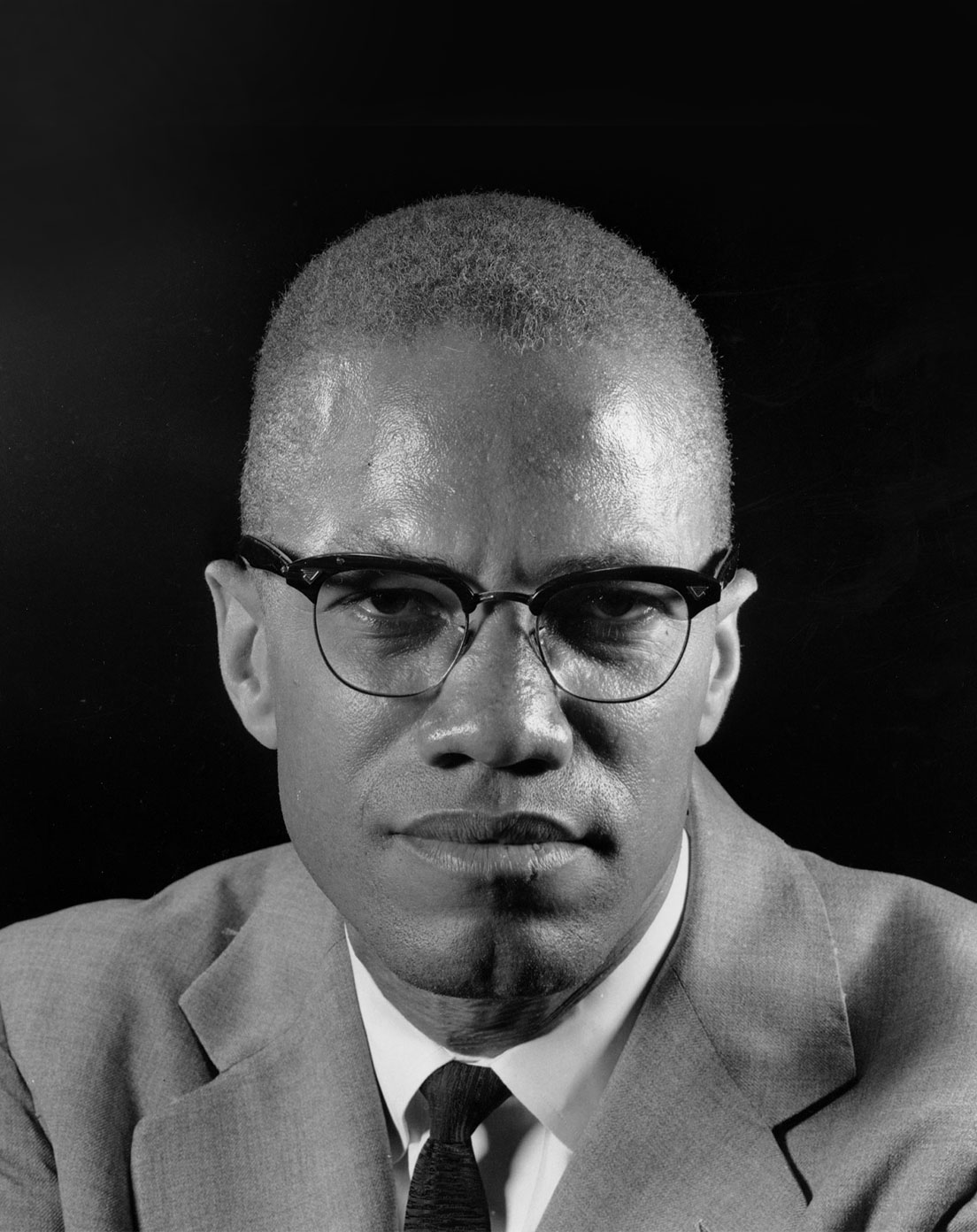

Alex Haley

“The Autobiography of Malcolm X” (1987)

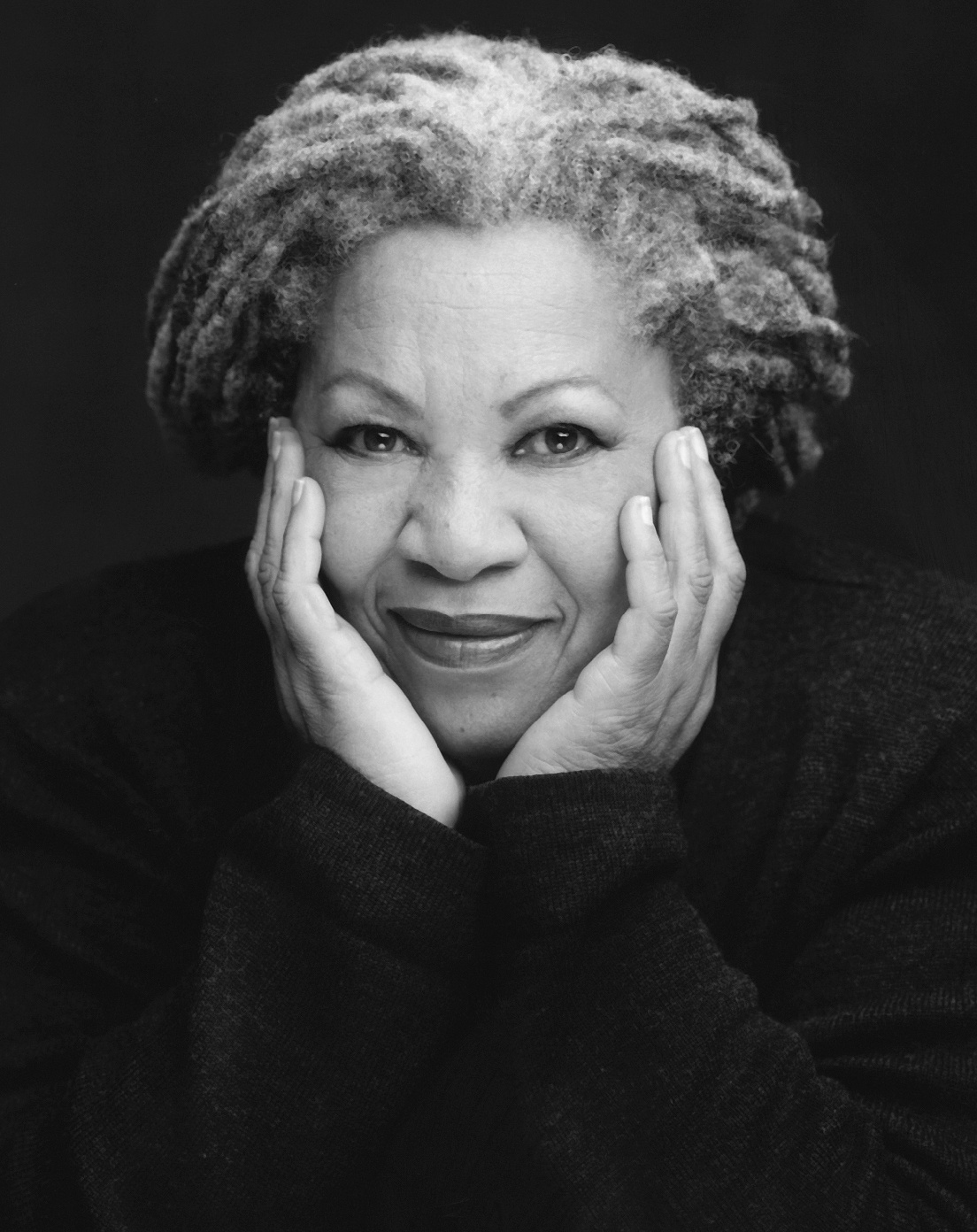

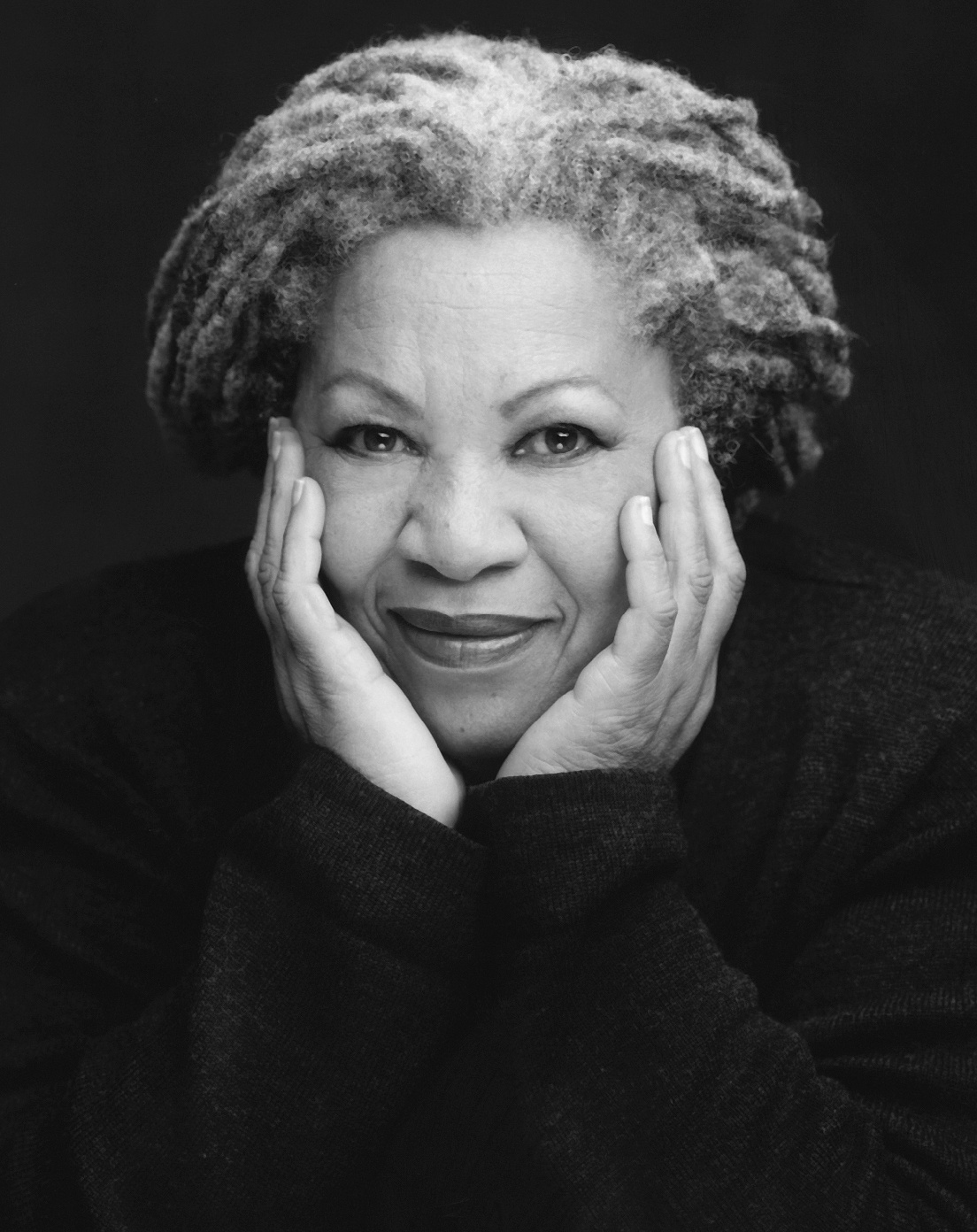

Toni Morrison

“Song of Solomon” (1977), “Sula” (1973) and “The Bluest Eye” (1970)

Langston Hughes

“The Weary Blues” (1925)

Zora Neale Hurston

“Their Eyes Were Watching God” (1937)

Zadie Smith

“White Teeth” (2000)

Isabel Wilkerson

“The Warmth of Other Suns” (2010)

Walter Mosley

“Devil in a Blue Dress” (1990)

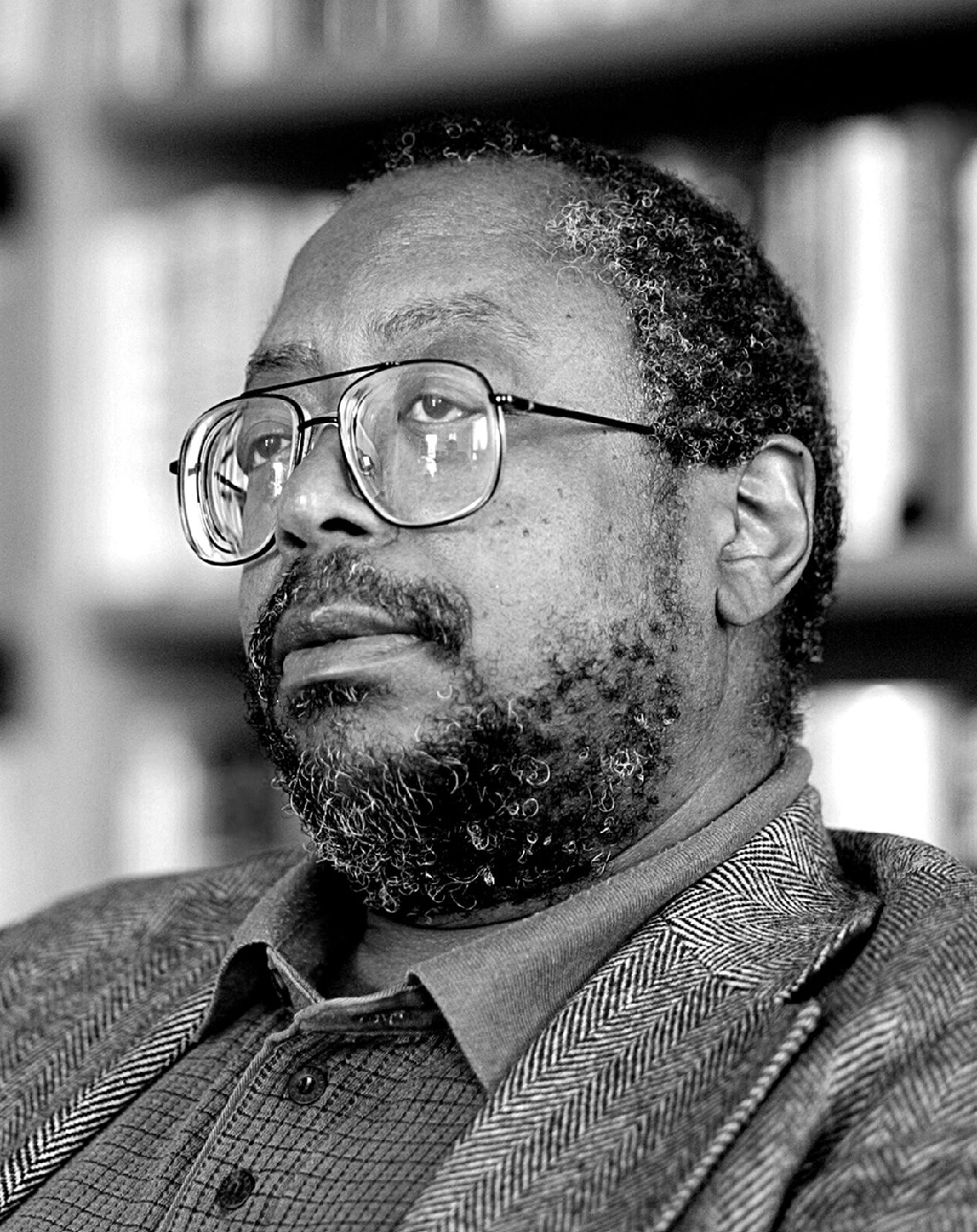

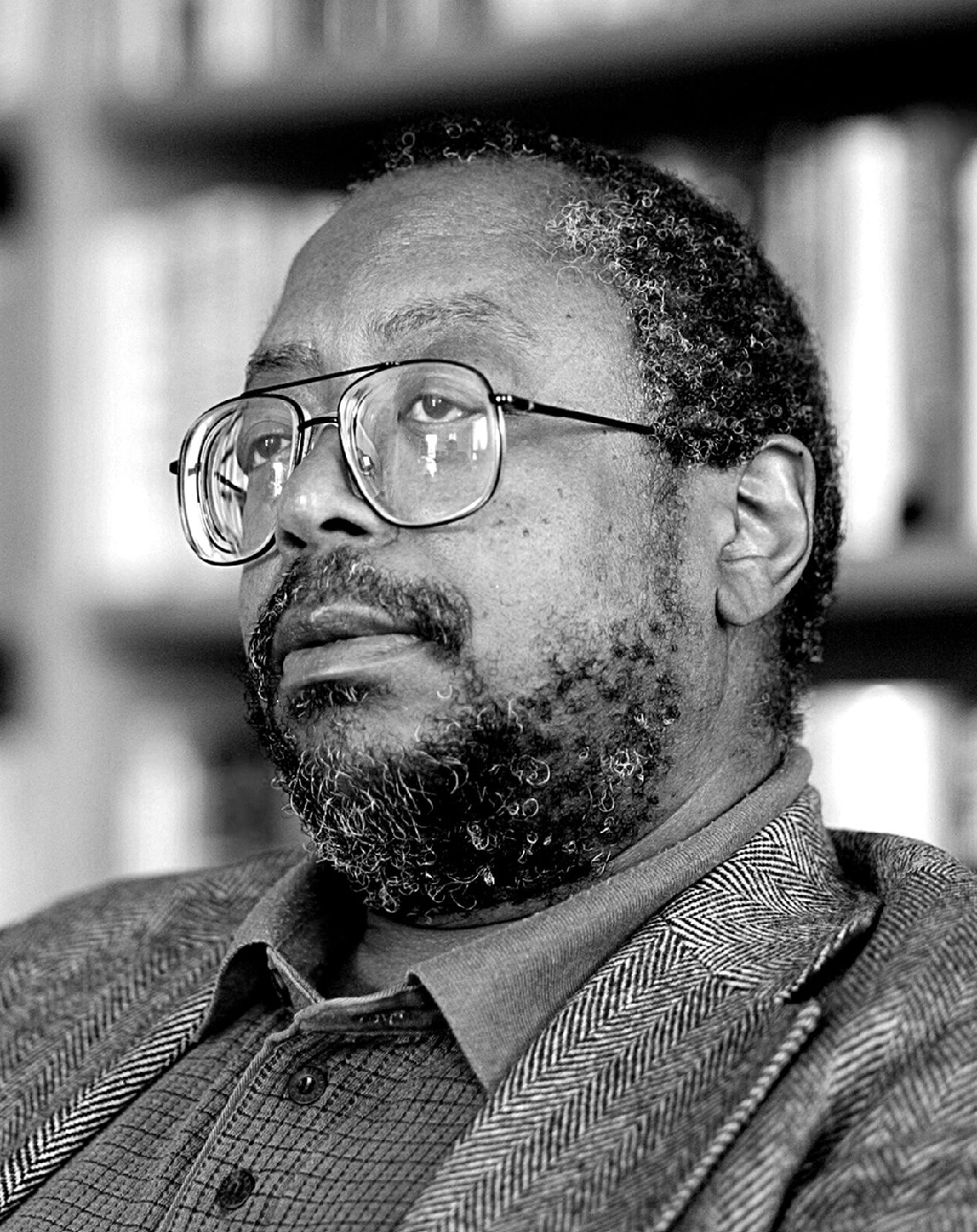

Ernest J. Gaines

“A Lesson Before Dying” (1993)

We realize the headline is a bit of hyperbole but in researching Mr. Gaines for this week’s exploration of his life and works, we realize that he has a tremendous way with words. Not just on the page, but in interviews as well. English rolls off his tongue in a way that to the ear often sounds like poetry, and his fingers create rich worlds without burdening the reader with five-dollar words. We gathered some of his best quotes from interview past so you could see for yourself how he does it:

I write as well as I can and I learned from reading people like Hemingway, and others, that writing less is better. If I can say something in five words instead of seven words, I’ll use five. Sometimes it’s a little difficult for some people to understand it if they don’t read very much.

I’m not one of those people who has a large, wide brush for canvas. I can’t use words, words, words. I try to get as few words as I possibly can to express myself. I believe in telling a story when I’m writing. I’m not just giving a philosophy or an ideology or social writing. I try to be honest with all my characters whether they’re good or bad, cowardly or brave.

Does the writer capture description well? Does he use dialogue well? Are things believable? Is the writer prejudiced when describing blacks or whites, males or females? I think readers look through all these things and then draw their own conclusions. You know, readers see things their way. You might have a good story and you don’t know how to write it. You can have a bad story and not have a thing in the world to say, but you can write so well. . . . I’ve had those kinds of students. They have nothing to say, but they’re good at writing.

I did not know I wanted to be a writer as a child in Louisiana. It wasn’t until I went to California and ended up in the library and began reading a lot that I knew I wanted to be a writer. I read many great novels and stories and did not see myself or my people in any of them. It was then that I tried to write. There were very few people on the plantation who had any education at all, especially the old people my aunt’s age and my grandmother’s age. They had never gone to school, and they didn’t have any books. I used to write letters for them. I had to listen very carefully to what they had to say and how they said it. I put their stories down on paper, and they would give me teacakes. If I wanted to play ball or shoot marbles, I had to finish writing fast. So I began to create. I wrote about their gardens, the weather, cooking, preserving, anything. I’ve been asked many times when I started writing. I used to say it was in the small Andrew Carnegie Library in Vallejo, California, but I realize now that it was on the plantation.

What I would like people to say is that he wrote as sincerely as he could possibly write. He could have done more writing and that’s the way I feel about myself. I could’ve done more. I’m proud of most of what I’ve done, but I could have been better. I might have studied harder and written longer. I could’ve spent a longer time at my writing desk.

My six words of advice to writers are: “Read, read, read, write, write, write.” Writing is a lonely job; you have to read, and then you must sit down at the desk and write. There’s no one there to tell you when to write, what to write, or how to write. I tell students if they are going to be writers, they must sit down at a desk and write every day.

Each week, we’ll be helping you to get to know our winners better (what a great bunch they are) and highlighting the best of their work, interviews and essays. This week, our focus is on Ernest J. Gaines, our 2000 Lifetime Achievement winner.

“…to me, without books, life would be a mistake.” In this video with the National Endowment for the Arts, Ernest J. Gaines sat down to talk about one of his most popular books, A Lesson Before Dying. He talks about getting paid to write letters for the less-literate members of the community (getting a nickel or a tea cake for his efforts), about learning from white writers, about his humble beginnings. It’s worth watching if you value good conversations about literature.