Riders heading to downtown Cleveland on the RTA’s Red Line may have noticed quite a few more pops of color adorning the city landscape over the past two weeks. The colors have a story, and each story comes from a work or writer in the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award canon.

Inter|Urban, the collaboration among the City of Cleveland, the Cleveland Foundation, North East Ohio Area Coordinating Agency, RTA and LAND studio, has filled the 19-mile stretch from Cleveland Hopkins International Airport and into downtown Cleveland with bright, vibrant murals. Coming up in time for the Republican National Convention in July will be two photo installations. All the art is inspired by Anisfield-Wolf texts and writers.

Seventeen artists from around the world converged on Cleveland in June for a public art blitz, creating an outdoor gallery and anchoring installations at the airport and Terminal Tower. Eight artists are based in Cleveland, with the others representing South Africa, Michigan, Pennsylvania, California, Hawaii, and Florida.

“This marvelous project moves the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards out into the city, showcased through original art spaced along the everyday paths of thousands of commuters,” said Karen R. Long, who manages the prize. “We expect the murals and the photography to start important conversations and serve as gateways to the books themselves, and the galvanizing ideas they contain.”

View the artworks below and hear from the artists in their own words how each piece came to be. Photos, unless otherwise specified, taken by Brandon Shigeta:

INSPIRATION: “Sophie Climbing the Stairs,” a poem from Dolores Kendrick’s The Women of Plums, which won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 1990, and consist of poems in the voices of slave women. LOCATION: Lorain Avenue underpass

San Francisco muralist Aaron De La Cruz drew inspiration from a selection of Dolores Kendrick’s “Sophie Climbing the Stairs,” about an enslaved woman sneaking off to read. The passage evoked a memory of his parents speaking in Spanish to keep their conversations a mystery to the young De La Cruz and his brother. Drawing off the theme of literacy, his mural features deconstructed letters and punctuation marks.

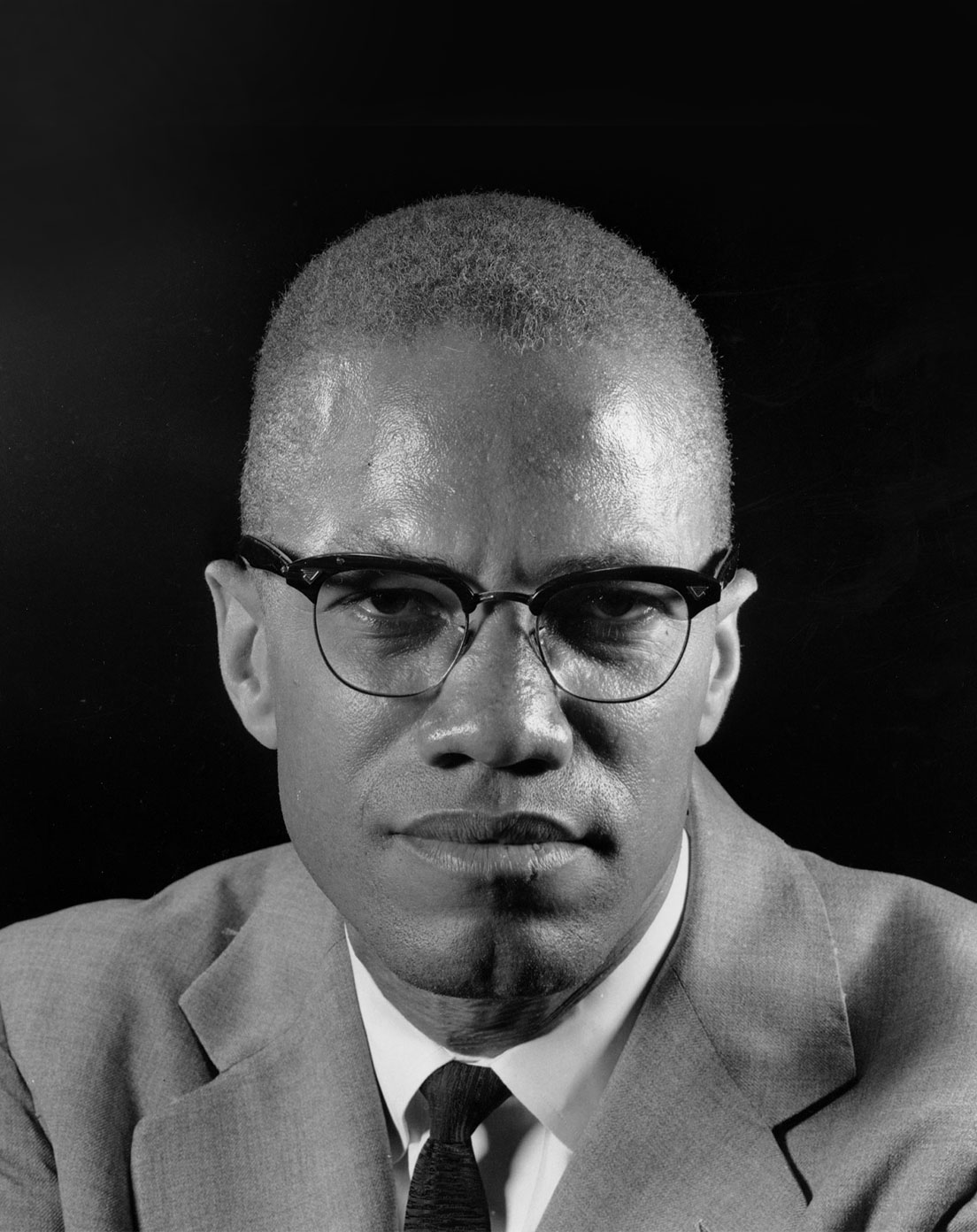

INSPIRATION: The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Alex Haley, a 1966 Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards winner

LOCATION: W.25th and Columbus Street

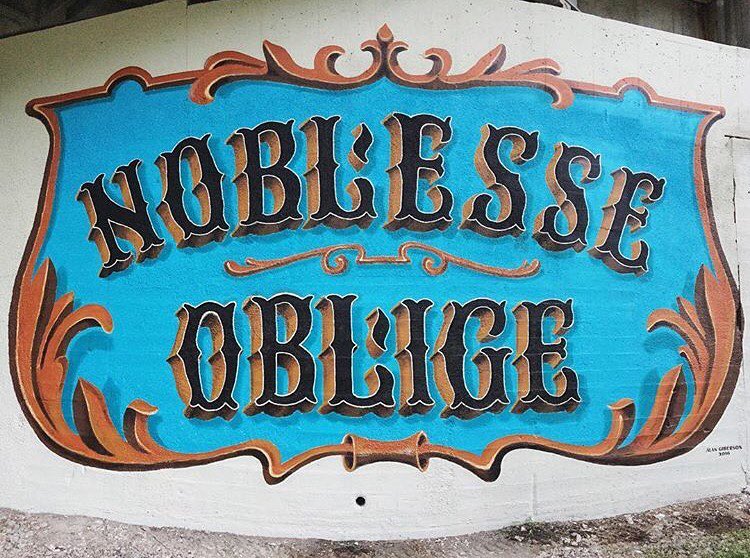

Cleveland artist Alan Giberson’s mural came from a brief scene in The Autobiography of Malcolm X, when a New York Times reporter meets the civil rights leader for the first time. “Noblesse Oblige” is a French phrase referring the responsibility of those with privilege to extend generosity to those less fortunate. The artist, who specializes in hand-painted signage and gold-leaf lettering, was eager to tackle this project. “This was a big challenge, being the largest thing I’ve ever painted.”

INSPIRATION: The End by Elizabeth Alexander from American Sublime. The poet won for Lifetime Achievement in 2010.

LOCATION: East 9th Street Wall, east of Tower City Station

Amber Esner, a Cleveland illustrator, was struck by Alexander’s ode to the dissolution of a relationship, as she lists the items left behind after a breakup. “My concept is based around the process of how people deal with loss by letting go of — or holding on to — specific objects,” she writes.

Cleveland illustrator and writer Margaret Kimball drew upon Martha Collins’ White Pages, a collection of untitled poems that explore white privilege and the ongoing racial divide in America. Kimball latched on to the repetition of the phrase “Yes, but” within the poem and used a minimalist color scheme to make one word prominent—YES. “The word is inclusive and strong and in this case has no strings attached, nothing to interrupt it,” Kimball writes.

If you happen to be in the passenger seat as you’re driving to and from Cleveland Hopkins airport, take a look around to see if you can spot these 35-foot tall overpass pillars, designed by Detroit artist Louise Chen. “The totem pillars are a celebration of the way cultures represent themselves in the language of ornament, with design inspired by many different cultures spanning the world,” she writes.

The Philadelphia-based artist describes this piece, titled “Unmask,” as “a visual metaphor about self-awareness, self-reflection and perception.”

INSPIRATION: Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (2011) by David Eltis and David Richardson & A Holocaust Called Hiroshima by Ronald Takaki, who won an Anisfield-Wolf award in 1994

LOCATION: East 9th Street Wall, east of Tower City Station

Cleveland artist Osmad Muhammad used his mural to make a statement about national and global atrocities. The burning woman in foreground is a reference to Hiroshima and the burning ships depict the slave trade throughout the Americas.

INSPIRATION: Montage of a Dream Deferred by Langston Hughes

LOCATION: W.25th and Columbus Street

Published in 1951, Langston Hughes‘ Montage of a Dream Deferred reads like a jazz record, full of conflicting rhythms and short bursts of animation. Cleveland artist Ryan Jaenke took Hughes’ melody and translated it to this mural on Cleveland’s west side. Hughes won his Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 1954.

INSPIRATION: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz, winner of both a Pulitzer Prize and an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2008

LOCATION: Old Abutment West, east of Tower City Station

Jasper Wong, Hawaiian artist and co-curator of the Interurban project, explored the themes of luck that featured prominently in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. He peppered his mural with black cats and broken down cars (symbols of bad luck) and rabbits (symbols of good luck).

INSPIRATION: “The Danger of a Single Story” — Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2009 TED talk She won an

Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for her novel “Half of a Yellow Sun” in 2007. LOCATION: Underpass pillars on I-90W

Detroit artist Ellen Rutt used bold geometric patterns to transform these underpass pillars. Her “Patchwork Cleveland” mural was inspired by Adichie’s call to avoid “making generalizations about culture based on a singular experience or limited knowledge.” When Rutt moved to Detroit in 2011, she quickly realized the broader narrative about the Rust Belt city was flawed. “It was in Detroit, surrounded by amazing street art, that my interest in murals grew from awefilled admiration, to an unstoppable desire and ultimately, an incredibly important part of my art practice,” she writes.

INSPIRATION: The Rain by John Edgar Wideman, who won a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011

LOCATION: New East 9th Street Wall, east of Tower City Station

A Cleveland native, Darius Steward is a graduate of the Cleveland Institute of Art. His mural features yellow as a primary color, the prominent color from John Edgar Wideman’s short story, “The Rain.”

INSPIRATION: Language as a boundary by Wole Soyinka. He won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 1983 for his memoir Ake: The Years of Childhood, and again for Lifetime Achievement in 2013.

LOCATION: Old Abutment East

South African artist Faith47 brought her international murals to Cleveland as part of her Psychic Power of Animals series, which attempts to “bring the energy of nature back into the urban metropolis.”

“There’s an inherent irony in recreating nature on cement, so the series is a nostalgic reminder of what we’ve lost but also an attempt to reintegrate that into the present,” Faith47 writes on her website. “We have become so distanced from nature, so these murals are an attempt to reconnect us with the natural world.”

INSPIRATION: The Boat by Nam Le This short story collection won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2009.

LOCATION: Mirrored wall

San Francisco artist Brendan Monroe took cues from the dangerous sea voyage in Nam Le’s The Boat as he created this expansive mural. Look closely and you can see a child overboard.

INSPIRATION: The short story “5 Dollar Bill” from Dorothy West’s collection The Richer the Poorer. West won our lifetime achievement award in 1996.

LOCATION: New East 9th Street Wall, east of Tower City Station. Photo by Amber Esner

“My father and I had a complicated relationship like the one in the story,” Kosman wrote, “and he died when I was fairly young, but he taught me most of the lessons I use now in my everyday life.”

If Edith Anisfield Wolf were alive today,” Detroit artist Pat Perry wrote, “I think she’d be encouraging us all to take direct aim at the great moral and social crises of our time. I can earnestly say that I think she’d be proud to see folks employing ideals taught to us by the past, in order to tackle issues of the present.”