Jill Lepore is restless.

The Harvard historian prefers to walk while she thinks, and stand when she talks. And so she stood before perhaps 800 guests gathered in Cleveland to hear her ponder whether a divided nation can own a shared past.

“A nation born in contradiction, liberty in a land of slavery, will fight forever over the meaning of its history,” she writes in These Truths: A History of the United States, a 1,000-page civics lesson that W.W. Norton will publish in September.

Sweeping American histories were once common, particularly in the 1930s, Lepore said. They mustered an argument for American democracy, a rebuttal in the teeth of Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and their ilk. Now the nation is divided down the middle, she observed, with the hero of one half – Barack Obama or Donald Trump – serving as the villain of the other.

Asked about economic inequality, Lepore acknowledged its rise since 1968. But it is race, not class, in her estimation, that undergirds our systems: “Race is the foundation of our politics in a way that is mainly horrifying,” she said. “I put race squarely at the center of the history of the United States – it really is the driver of our political change.”

With her third history, New York Burning, Lepore won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2006. It explores 18th-century, pre-Revolutionary War Manhattan, specifically the winter of 1741, when ten fires beset the seaport village. With each blaze, panicked whites saw more evidence of a slave uprising. In the end, 13 black men were burned at the stake, 17 hanged, and more than 100 black women and men were thrown into a dungeon beneath City Hall.

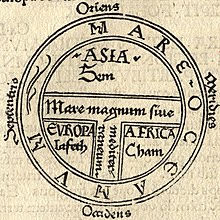

In her Cleveland presentation, Lepore, 51, started earlier still, noting that the very decision of where to begin a history is political. She flashed up an image on the multiple screens of the Maltz Performing Arts Center. Called the T-O Map (left), it dates to Medieval Spain and is considered the first conceptual map Westerners made of the world.

In her Cleveland presentation, Lepore, 51, started earlier still, noting that the very decision of where to begin a history is political. She flashed up an image on the multiple screens of the Maltz Performing Arts Center. Called the T-O Map (left), it dates to Medieval Spain and is considered the first conceptual map Westerners made of the world.

Next came the 1507 Waldseemuller map, made by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemuller. Its enormous popularity helped cement the name “America” for the new lands. “Like much of history, the naming was a crapshoot,” Lepore said.

She flashed up a painted portrait with a globe meant to cement Queen Elizabeth’s dominance over the new world (1588) as well as Powhatan’s Mantle (1607), meant to illustrate something similar about the regency of a Chesapeake chief.

The physical Constitution itself, widely printed and distributed in 1787, is a kind of map that argues “the people are sovereign by virtue of reading, a wholly new idea that sticks,” Lepore said. “The debate over the Constitution was really a strong one with Alexander Hamilton asking if people can rule themselves by coming up with a set of laws that govern by reason and choice instead of accident and force.”

One of the scholar’s favorite images portrays Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and feminist, knitting the nation – made in 1864, a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. The outline of the United States lies in yarn on her lap.

One of the scholar’s favorite images portrays Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and feminist, knitting the nation – made in 1864, a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. The outline of the United States lies in yarn on her lap.

Eight years earlier came a depiction that embraces the “technological sublime,” the idea that a technological fix could bind up the nation. In 1856 that was the transcontinental railroad. In 2000, it was an issue of Wired Magazine arguing that the internet would heal the nation’s political divisions in ten years.

As for the present, “historians make terrible prophets,” Lepore declared.

She noted that guns and abortion were apolitical topics a half-century ago. Now they serve as mirrored partisan gold-standards: Conservatives see guns as freedom and abortion as murder and liberals see guns as murder and abortion as freedom.

Lepore preferred, in writing the nation’s history, to dwell on a conversation between Henry Longfellow and his close friend Charles Sumner, during the perilous year 1848. The poet shared his new work, “The Building of the Ship of State,” in which the country is wrecked and sinks. Sumner implored Longfellow to give it a more optimistic cast. And when the poet did, it contained the famous lines: “Thou, too, sail on, O Ship of State!/Sail on, O Union, strong and great!”

Abraham Lincoln read these lines and wept. Sumner’s argument for optimism spoke deeply to Lepore. She deplores the fashionable radical pessimism – right or left – that characterizes our day, calling it “a kind of political cowardice.”

She cited a survey indicating that in the last year, only one in four Americans has had a political conversation with someone with whom they disagree – a perilous fact in itself.

Ever the historian, she suggested that citizens “wrestle with the facts, presume good will, use debate, examine the materials and make some arguments about the evidence.”