As we bid adieu to 2018, allow us to shine a last, lingering reading light on ten highlights: the year’s titles from Anisfield-Wolf Book Award winners. It should surprise no one that several are already acclaimed as the best-of-the-year. All are worth reading.

“American Histories: Stories” by John Edgar Wideman

In the latest literary stroke from an American master, these 21 short stories “are linked by astringent wit, audacious invention and a dry sensibility,” according to one critic. Another calls them “irresistible” and “profoundly moving.” The first, “JB & FD” imagines conversations between John Brown and Frederick Douglass. Another tale takes up with Jean-Michel Basquiat. Still another, “Williamsburg Bridge,” rests with a man contemplating his intent to jump into the East River. When Wideman won an Anisfield-Wolf lifetime achievement award in 2011, he told the crowd a writing life still lay ahead. Now 76, the former Rhodes Scholar from Pittsburgh and MacArthur “genius” recipient speaks the truth still.

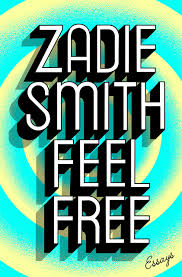

“Feel Free” by Zadie Smith

The exuberant, cerebral novelist collects her essays and landed on six best-of-the-year lists. She arranges the book into five sections: “In the World,” “In the Audience,” “In the Gallery,” “On the Bookshelf” and “Feel Free.” All the writing dates to the Obama administration. Maureen Corrigan describes the best of it, like Smith’s essay “Notes on Attunement” about disliking and then loving Joni Mitchell’s voice, as freeing. Also here is Smith’s much discussed essay on “Get Out,” in which she marks as fantasy “the notion that we can get out of each other’s way, mark a clean cut between black and white.” The cultural critic is often joyful, essentially saying art makes and marks freedom. Smith won her Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for “On Beauty” in 2006.

“Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom” by David W. Blight

This magisterial biography argues that its subject was among most transformative figures of the 19th-century. It begins with President Obama speaking of Douglass’ “mighty leonine gaze” at the 2016 dedication of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It ends with the Robert Hayden’s superb poem “Frederick Douglass” that asserts when freedom comes, it will be “with the lives grown out of his life, the lives/Fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.” Blight, a fluid, graceful writer and Yale historian, has dedicated a lifetime of scholarship to this text. He won his Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2012 for “American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era.”

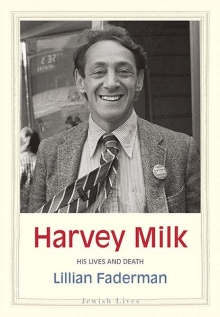

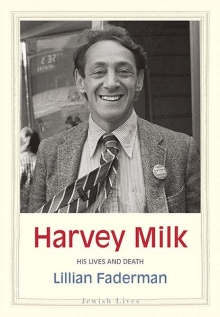

“Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death” by Lillian Faderman

In her crisp, beautifully researched biography, Faderman makes the case that Harvey Milk led many lives before he was martyred: Navy diver, math teacher, Wall Street securities analyst, Broadway gofer. Only in his final few years did he find his footing as a San Francisco politician. She begins by describing him as “charismatic, eloquent, a wit and a smart aleck,” and depicts a complex man with real enemies, real courage, real flaws and boundless energy. Much that animated Milk traces to his Jewish roots, making this portrait a snug fit in the Yale University Press’ acclaimed Jewish Lives series. Faderman won her Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for “The Gay Revolution,” another definitive history, in 2016.

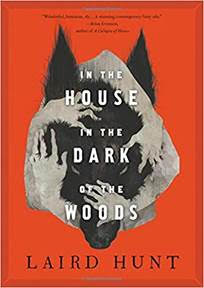

“In the House in the Dark of the Woods” by Laird Hunt

Every good book list should contain a fable, and the gifted Hunt delivers a stellar haunting with his latest, palm-sized novel. It opens in colonial New England with the classic trope: a woman goes missing in a forest. Hunt, a Brown University professor, lets his eighth novel excavate ancient fears of females kidnapped, women straying and maternal abandonment. But here the central figures narrates her own agency: “Through the dark woods I walked, thinking less and less of my son and of my man.” Hunt creates rapt historical fiction, as he did in “Kind One,” his Anisfield-Wolf honored novel from 2013. It serves as the start of a profound Midwestern trilogy, including “Neverhome” and “The Evening Road.”

“Invisible” by Stephen L. Carter

Subtitled “The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster,” this biography of the author’s grandmother astonishes. Eunice Hunton Carter, herself the granddaughter of slaves, was 8 in 1907 when she declared she wanted to be a lawyer “to make sure the bad people went to jail.” A team of 20 crackerjack attorneys assembled to convict Lucky Luciano; the other 19 were white men. Thanks to Carter’s strategy, the prosecution won. The author, a Yale law professor, realized while writing this book that an earlier novel had been an unsuccessful homage to this formidable, intimidating Harlem original. In 2003, he won an Anisfield-Wolf prize for “The Emperor of Ocean Park.”

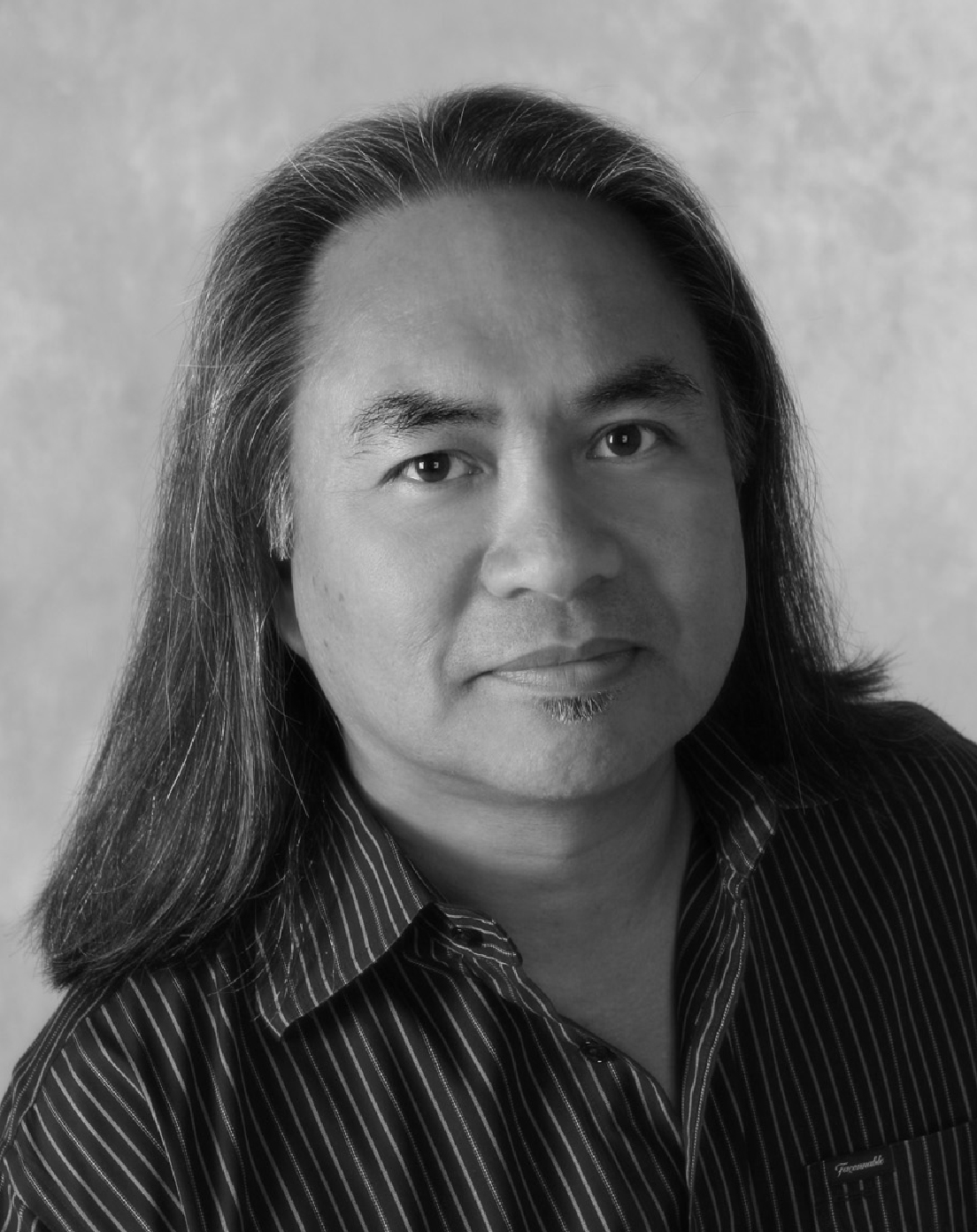

“John Woman” by Walter Mosley

The author thought about this political and philosophical thriller for 20 years. It contains a murder and a disappearance, but it is not, Mosley says, a mystery. Instead it centers on a boy, Cornelius Jones, who is 12 as the story begins. His father is a silent film projectionist in the East Village; his mother is a sensualist backing out of Cornelius’ life. Five years later, Cornelius reinvents himself as “John Woman” and starts an intellectual movement drawing on his father’s notions of the slipperiness of history. The author, who won his Anisfield-Wolf prize in 1998 for “Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned,” describes his new book as “a study of a man who stalks a prey (history) that is at the same time tracking him.”

“A Portrait of the Self as Nation: New and Selected Poems” by Marilyn Chin

In her first book since winning a 2013 Anisfield-Wolf award for “Hard Love Province,” Chin draws together 30 years of dazzling, transgressive, witty work as an activist poet. “From the start of my career I waxed personal and political and have sought to be an activist-subversive-radical-immigrant-feminist-international-Buddhist-neoclasical nerd poet,” she writes from her home in San Diego, where she teaches comparative literature at the state university. Chin is masterful at making pain both visible and less tragic by throwing it into a cheeky, double-vision, East-West light. She writes to her grandfather, on his 100th birthday, “This is why the baboon’s ass is red.”

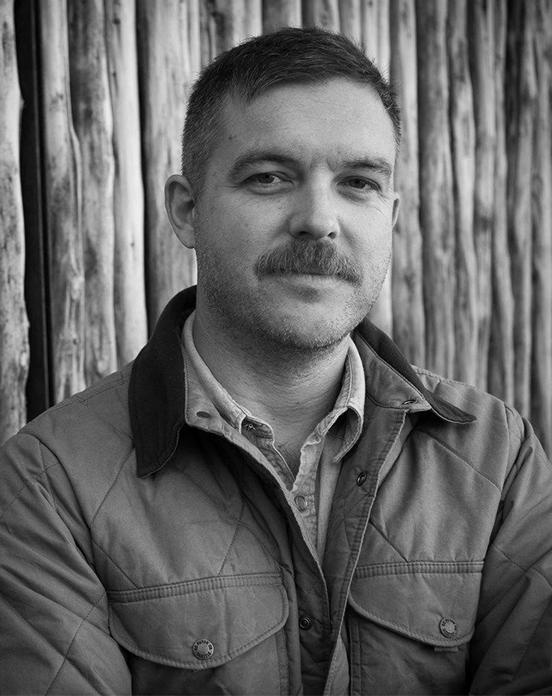

“A Shout in the Ruins” by Kevin Powers

The author of the deeply moving debut novel “The Yellow Birds,” which won an Anisfield-Wolf Book award in 2013, shifts his story-telling onto his home turf of Richmond, Va. He unspools two intertwined tales – one set at the end of the Civil War; the second steps off 90 years later as construction for the Richmond-Petersburg turnpike dismantles the city’s African-American neighborhood. Powers has said that he is drawn to stories of communities responding to violence. Called “gorgeous, devastating” in The New York Times, the novel suggests readers grasp that “the truth at the heart of every story, that violence is an original form of intimacy, and always has been, and will remain so forever.”

“Washington Black” by Esi Edugyan

This picaresque yet deeply haunting third book from a brilliant Canadian author landed on ten best-of-the-year lists. She won an Anisfield-Wolf award in 2012 for her equally stunning “Half-Blood Blues,” a European war novel set to a jazz beat. Both books were short-listed for the Booker Prize. In “Washington Black,” Edugyan begins on a sugar plantation in Barbados, where her title character is an 11-year-old who escapes bondage in a hot-air balloon piloted by the master’s brother. The story is an original in the derring-do explorer’s genre, probing self-invention, betrayal and the gradations of freedom — particularly as it limits both men. And the writing here moves like clear water across landscape and dialogue.

A Shout in the Ruins has a ring to it – both as a book and as a title that a poet would craft.

Novelist Kevin Powers spent six years writing his lyrical and violent story set in “the ruins” of Richmond, Virginia, the place where he was born and raised. The author anchors one narrative strand in the ruins of the Civil War; the second unspools 90 years later, during the ruins of the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike construction that knocked apart the old Jackson Ward neighborhood of the city.

Readers can glimpse a thematic through-line from Powers’ fierce and luminous first book, The Yellow Birds, an elegiac story centered on a U.S. soldier named John Bartle returning from the Iraq war. It won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for fiction, as well as the PEN/Hemingway award.

“I will probably always be interested in the way that violence affects communities, how people respond to those sort of situations and how people put a life together when not all the pieces are intact,” Powers said in 2013 in Cleveland. As a teenager, he served as U.S. army gunner in Mosul and Tal Afar, Iraq.

A Shout in the Ruins has a deep feel for blood-soaked Virginia. It becomes a multi-generational look at racism and intimacy in the context of war and ruin, American edition.

The story follows two couples: Rawls and Nurse, young people enslaved and in love, and their owners, Emily Reid Levallois and Antony Levallois, bound in marriage and unhappiness and treachery. Levallois is the region’s major landowner – his plantation is called Beauvais – and he sows menace in every direction.

As the book opens, Beauvais is burned, Emily either a ghost or an escapee from that place. The narrative scrolls backward to her midsummer birth, with Rawls as a little boy in the yard watching his mother rock the newborn, a “strange girl who would so influence the rest of his life.”

A few pages later, Rawls begins his nighttime courtship of Nurse, who asks him, “Why do you have a gait like a hobbled dog?” He shows her his feet, both big toes “docked,” or sliced off in childhood after he tried to escape. As the couple sits with this, “the common noises of the night returned. The nightjar’s solemn whistle. A fox scream in the distance. The world painted in shades of gray and lit solely by reflection.”

A mere 15 pages into the novel Powers has nestled beauty and horror together.

The second chapter pivots to George Seldom, an elderly black man losing his house to the 1956 turnpike construction. George takes his displacement as the cue to travel – with a copy of The Negro Traveler’s Green Book – toward a memory of the North Carolina cabin of the woman who raised him from a foundling.

At mid-book, the reader learns how George’s history links to Rawls, Nurse and the Levalloises; George never does. Powers alternates the two narrative threads in a way that complicates all their stories.

When Rawls, still enslaved, is brought home by a group of four white men enraged by him, only Antony Levallois is clear about punishment. The other three “had lived a long time under the assumption that the threat of retribution was enough of a deterrent to keep the course of their lives moving in a predictable direction. And further, their hesitance to use violence to enforce their mastery over those they owned was a sign of a deep well of kindness and loyalty that characterized the tangled knot of the relationships of all involved. Among the five men gathered beneath the colorless buds of the sycamore tree, only two were free of this illusion.”

Those two are Levallois and Rawls, “who had decided long before that a kind master was a terrible master to have.”

Powers bring a psychological acuity to A Shout in the Ruins. These insights and their consequences spill through all his characters, reaching George Seldom a century later, reaching Powers’ readers now.

Another son of Richmond, Tom Wolfe, put The Yellow Birds on par with All Quiet on the Western Front. Wolfe died last month at age 88. Let’s hope that Little, Brown & Co., which published both men’s work, delivered an early manuscript to the elder literary lion in time for him to read it.

“Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting” publishes this week, the first collection of poetry from Anisfield-Wolf fiction winner Kevin Powers. Here is the title poem:

I tell her I love her like not killing

or ten minutes of sleep

beneath the low rooftop wall

on which my rifle rests.

I tell her in a letter that will stink,

when she opens it,

of bolt oil and burned powder

and the things it says.

I tell her that Private Bartle says, offhand,

that war is just us

making little pieces of metal

pass through each other.

Powers, who grew up in Richmond, Va., enlisted the day after he turned 17. He served as a U.S. Army machine gunner in Mosul and Tal Afar, Iraq, in 2004 and 2005. Those years informed “The Yellow Birds,” a first novel that writer Tom Wolfe called “the All Quiet on the Western Front of America’s Arab wars.” Private Bartle is its narrator.

The new book contains 34 poems that well out of war, bafflement and remembrance, often speaking of mothers. They touch on rifles, men in bars, stretches of Texas and Nebraska and West Virginia. The book is dedicated to “my friends from the Boulevard.”

When Powers spoke in Cleveland last September, he said he hadn’t kept a journal as a soldier, that he didn’t have the stamina or mental reserves. But the books his mother mailed him were a lifeline, and he wrote some letters. Almost three years ago, a friend brought out one that he’d sent to her.

“I could see the point in the letter where I almost opened up, but didn’t,” he said.

In his penultimate poem, “A Lamp in the Place of the Sun,” Powers concludes with four short lines in plain language: “How long I waited/for the end of winter./How quickly I forgot/the cold when it was over.”

“Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting” is the first book of poetry that Little, Brown & Co. has published in 30 years.

Kevin Powers‘ The Yellow Birds has been called a “beautiful and horrifying trance of a book,” an unnerving look at the cruelty and arbitrary nature of war. He spoke with us in the calm before this year’s ceremony, happy to accept the award that in recent years has gone to Junot Diaz, Louise Erdrich, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Hear his remarks below:

Kevin Powers On Winning A 2013 Anisfield-Wolf Award For Fiction from Anisfield Wolf on Vimeo.

Kevin Powers didn’t flinch when the novelist Thrity Umrigar asked him a pointed question—had he considered incorporating substantial Iraqi characters in his much-honored novel “The Yellow Birds”?

Power’s first book, an impressionist portrayal of combat and its consequences during the Iraq War, won an Anisfield-Wolf book prize this year for fiction. The National Book Award cited it as “an urgent, vital, beautiful novel that reminds us through its scrupulous honesty how rarely its anguished truths are told.”

Umrigar, a professor of creative writing at Case Western Reserve University best known for her novels “The Space Between Us” and “The World We Found,” politely asked if Powers had thought to write a story that “would give the Iraq people agency?”

Powers, 32, nodded vigorously, standing at a lectern on the Case campus, and said he’d weighed that question. “Because I’m telling this single soldier’s story, I wanted to be true to his perspective, his inability to understand the larger picture,” Powers said of his narrator, Private John Bartle. “I wanted to stay true to the distance, the chasm that exists, in an unformed young person, not capable of these interactions.”

Powers himself joined the U.S. Army the day after he turned 17, serving as a machine gunner in Iraq in 2004 and 2005. He was deployed “outside the wire,” backing up infantry and cavalry in units trying to find Improvised Explosive Devices before they found their targets.

Thoughtful, soft-spoken and given to the “y’alls” of his Richmond, Virginia upbringing, Powers took 20 minutes to read the final chapter of “The Yellow Birds” to his Baker-Nord Center audience. It awakened in several veterans a desire to speak about the burdens they bury, and carry, from the killing they did and the dying they witnessed. The atmosphere was tense, and Powers listened long and intently. Three times he responded to statements from veterans with a quiet “absolutely.”

Occasionally, Powers said, someone will object. They will note that “War is hell” and assert there is nothing new to say. But, “it still feels necessary to me,” he said. “Until we can say, ‘War was hell,’ then somebody needs to keep saying it. We shouldn’t have the excuse that we didn’t know how bad it was.”

The writer assured his listeners that the specifics of “The Yellow Birds” “are very different from my own experience,” but acknowledged that he drew upon his own guilt and shame and attempts to make sense of his memories in crafting the novel.

“I spent four years writing it, more or less, in isolation,” he said. “I didn’t know if anyone would publish it or read it.” He often wrote until 3 a.m., persisting, he said, because writing was the way he makes sense of the world.

“I can’t separate reading and writing,” he said. “If I wasn’t a reader, I wouldn’t be a writer. I simply have never found a better way of dealing with the confusion I feel when confronted with the world.”

Powers didn’t keep a journal as a soldier, saying he didn’t have the stamina, or the mental reserves. But the books his mother mailed him were a lifeline, and he wrote some letters. About two years ago, a friend showed him one that he’d sent to her.

“I could see the point in the letter where I almost opened up, but didn’t,” he said.

Next April 1, Powers will publish his first collection of poetry, “Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting.” And he has begun work on a second novel, set in hometown Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, and the ashes of the Civil War.

He notes, “I will probably always be interested in the way that violence affects communities, how people respond to those sorts of situations and how people put a life together when not all the pieces are intact.”

The road home from war is a long journey to rediscover who you are. Author Kevin Powers, who signed up for the Army at 17 and spent time as a machine gunner in Iraq in 2004 and 2005, wrote his award-winning novel, The Yellow Birds, as a way to help him process what he had experienced on the front lines.

“I started initially writing poems about the war,” he said during an interview with PBS NewsHour. “I’ve been writing poems and stories since I was about 13. And I realized that I needed a larger canvas to say what I wanted to say, to answer the question that people were asking me, which was what was it like over there.”

In the novel, we see life in a war zone through the eyes of 21-year-old private John Bartle. He is tasked with watching over Murph, a younger solider with less experience. Through startling imagery, Powers gives civilians a glimpse at the sacrifices service members make while protecting our freedoms. Powers explores the themes of helplessness and fear, of the harsh inequity on the battlefield, and of the struggle to rediscover “normal” after the tour of duty has ended.

The Yellow Birds won the 2013 PEN/Hemingway award for first fiction and was a finalist for the National Book Award. Powers holds an MFA from the University of Texas at Austin.

The jury has spoken and five new authors will join the Anisfield-Wolf family.

Our 2013 winners are:

“The 2013 Anisfield-Wolf winners are exemplars who broaden our vision of race and diversity,” said Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who chairs the jury. “This year, there is exceptional writing about the war in Iraq, slavery on a Kentucky pig farm, the Filipino experience in the U.S., and the complexity of families in which a child is radically different from parents.”

Gates directs the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research at Harvard University, where he is also the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor. He praised the singular achievement of Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian whose writing won a Nobel prize in 1986, three years after he won an Anisfield-Wolf award for his memoir, Ake: The Years of Childhood.

Cleveland Foundation President and Chief Executive Officer Ronald B. Richard said this year’s winners reflect founder Edith Anisfield Wolf’s belief in the unifying power of the written word.

“The Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards rose from the philanthropic vision of one woman who realized that literature could advance the ongoing dialogue about race, culture, ethnicity, and our shared humanity,” Richard said.

The Anisfield-Wolf winners will be honored in Cleveland Sept. 12 at a ceremony at the Ohio Theatre hosted by the Cleveland Foundation and emceed by Jury Chair Gates. Stay tuned this week as we profile each of our 2013 winners.