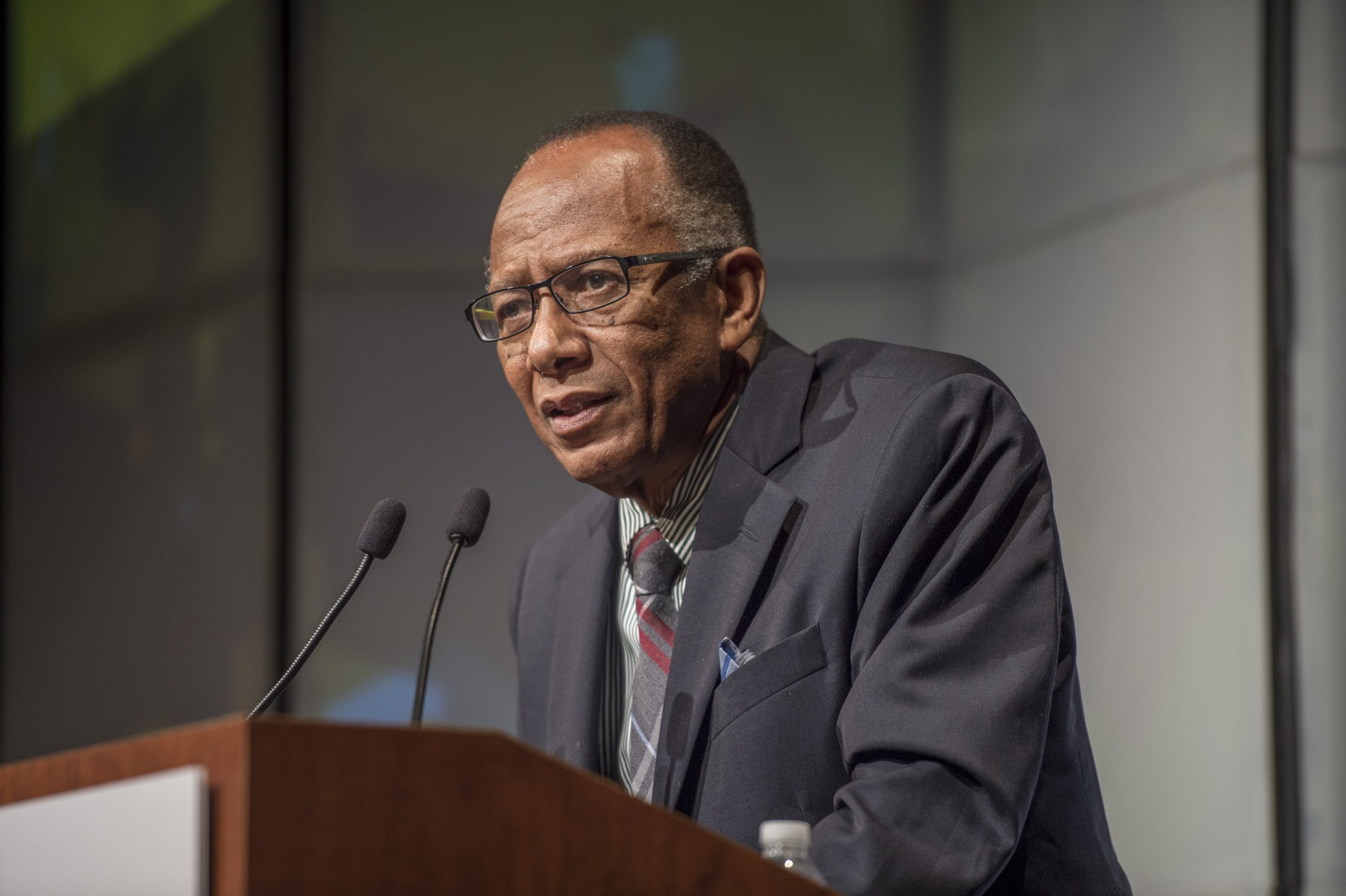

Orlando Patterson, the public intellectual and Harvard University sociologist, made a deep impression on his audiences in Cleveland in September. He received a rousing standing ovation, capping the awards ceremony in the Ohio Theatre of Playhouse Square. A few listeners walked out – which is also in keeping with the tenor of the reception to his globally influential scholarship.

“At Harvard, neither personal comfort nor false harmony have ever been his goal; he has always challenged his fellow faculty with his outspoken and fearless ideas,” said Anisfield-Wolf Jurist Steven Pinker as he introduced Patterson. “As colleagues, we have all found him forthright and reliably engaged; however, his gracious manner, and the musical Jamaican lilt of his penetrating discourse, often mask the uncomfortable truth that we have just been served.”

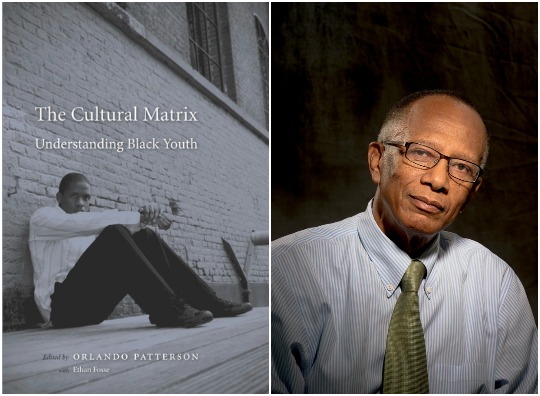

Patterson, 76, commanded his Cleveland audiences in just such manner, both during his acceptance and his lecture the preceding afternoon at the Baker-Nord Center for Humanities’ Harkness Chapel. Both set of remarks, in turn, rest on “The Cultural Matrix,” a set of essays Patterson edited with his doctoral student, Ethan Posse. He also applied them to an essay after the response in Baltimore to Freddie Gray’s death in police custody in the New York Times.

At the awards ceremony, Patterson told Clevelanders, “Few other groups, with the possible exception of Jews in Europe, have contributed more to the culture of the group that dominated and excluded them than black Americans – in music, dance, theatre, literature, sports and more generally in the style and vibrancy of its dominant culture, America is indelibly blackish. Trying to imagine America without blacks is like trying to imagine Lake Erie without oxygen.”

Here are Orlando Patterson’s full remarks at the 2016 Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. If you’d like to watch his acceptance speech, click here:

Thank you very much for that generous introduction, Steve. I am deeply honored by this award, made all the more gratifying by the fact that one of my dearest and most esteemed friends and colleagues is the person chosen to introduce me, based on remarks prepared by another greatly admired colleague and friend, Henry Louis Gates.

Cleveland Foundation President Ronald Richard, organizers and jury members of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, Ladies and Gentlemen, in the few minutes that I have your attention, I want to reflect aloud with you on two great paradoxes of “race” in American civilization.

The first is the fact that, going back to the earliest years of the Republic, we find that Black Americans, while being exploited as slaves and workers, and while being shunned socially into rural and urban ghettos, have nonetheless been embraced culturally. Few other groups, with the possible exception of the Jews of Europe, have contributed more to the culture of the group that dominated and excluded them, than black Americans—in music, dance, theatre, literature, sports and more generally in the style and vibrancy of its dominant culture, America is indelibly blackish. Trying to imagine America without blacks, is like trying to imagine Lake Erie without oxygen.

The second paradox of race in America came with our glorious civil rights revolution. And it was a revolution, let us not forget it, as we seem prone to do today in expressing our outrage at the brutality of our penal and security system. In righting the racial wrongs of its past America did what no other white majority society in the world has been able to do—it opened its public and civic space to its once shunned black minority. Today black Americans are major players in the nation’s political and civic life, the election of President Obama being the capstone– a monumental one to be sure–but the culmination, nonetheless, of this great struggle by our civil rights fathers to achieve what Martin Luther King called the beloved community. Let us give praise where praise is due: our great nation is the supreme model for the rest of the world of how the polity of a great nation, the most powerful on earth, can integrate into the innermost corridors of power, the leaders of its once shunned minority.

Cultural integration and influence out of all proportion to their size, on the one hand, and political and civic incorporation, on the other, are the two great achievements or American civilization with respect to its African-American minority.

And yet, and yet, at the same time that we have witnessed this magnificent political and cultural process, this nation continues to witness the incredible social isolation and economic disadvantage of the black minority as well as the unprecedented and outrageous incarceration of black youth, most for crimes that all other civilized nations would treat as minor offences deserving rehabilitation rather than incarceration. It is truly amazing that, for all this progress black Americans remain today almost as socially segregated as they were in the late sixties; that for all this cultural and political progress, combined with striking changes in the racial attitudes of white Americans, black Americans are still twice as unemployed as white Americans, that they continue to earn 65% of the median income of white Americans, exactly the same proportion that they earned in 1970, that the typical white household has 16 times the wealth of a black one, that one in 3 black youth are certain to spend part of their lives in prison, that the police of this nation still enter and treat black neighborhoods as if they are an occupying army and still feel empowered to cut down our black youth with impunity.

Nowhere in America are these two great paradoxes more evident than in this great city of Cleveland and the state of which it is a part. Last night I witnessed the extraordinary cultural presence of black America in our cultural life as I sat with the largest and most integrated audience I have ever seen, listening in rapt attention and near reverence to Rita Dove reading her gloriously American poems. And it is Cleveland and the state of Ohio, black and white, that twice voted for, and made possible the election of a black man to the nation’s and the world’s most powerful position.

And there was that amazing civic occasion several months ago when over a million persons turned out on the streets of your city to celebrate and worship the youthful, magically talented athletic gods that had brought glory and an unprecedented sense of civic pride to your city.

And yet, and yet, how many of those who came to cherish and give thanks to the young black heroes, on waking up next morning and seeing someone who looked like LeBron James moving in next door could resist the impulse to make a panic call to their real estate agent?

So this, ladies and gentlemen, in a nutshell is the great challenge that awaits us: to solve these two intertwined paradoxes of our national life. It can be done. Let us not be crippled by the miasma of pessimism that now stifles us. Let us not generalize our anger and outrage at the behavior of the nation’s police forces to chronic pessimism about the state and future of race relations in America. For if there is one thing that will ensure that the remaining work to be done in erasing racial bias and inequality in America will never be achieved, it is pessimism about it ever happening. Pessimism is a self-fulfilling malady.

What is needed is that same sense of racial justice and optimism about the future that animated the philanthropy of Edith Anisfield- Wolf. That same conviction about the possibility of America to change that inspired W.E.B DuBois and the other great political and cultural heroes of the Jim Crow era, and that motivated Martin Luther King to struggle and give his life for an America that fulfilled the rights enshrined in its Declaration and Constitution. With that conviction, with that optimism about the capacity of this great nation to change, this last most urgent challenge of social and economic integration can be met. In spite of all the obstacles and pessimism so much on display today, it will be done. Of that I am completely confident.